Memories of a 2015 Tour of the Morefield Mine in Amelia, Virginia

by Kathy Hrechka, MSDC Member and MNCA Editor, with input from Laura Dwyer, Mike Kass, and Kenny Reynolds

Dr. Mike Wise presented “Pegmatites, Earth’s Most Amazing Rocks” to the Mineralogical Society of the District of Columbia (MSDC) on March 6. He spoke via Zoom since we have not yet resumed meeting at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). Mr. Tim Rose, our museum sponsor and club liaison, was also in attendance. After Mike’s educational program, which included his “Ten Commandments of Pegmatalogy,” we entertained a discussion about the pegmatite mine in Amelia, Virginia. A synopsis of Mike's talk is presented elsewhere in this newsletter.

We learned that Mike and Tim designed the exhibit in the museum, which is a replica of the Morefield Mine in Amelia, Virginia. While recently volunteering in the NMNH’s Geology, Gems & Mineral Gallery, I revisited the Morefield Mine exhibit and took some photographs for this article.

MSDC members, Laura Dwyer, Kathy Hrechka, Ken Reynolds, and Mike Kaas recall visiting the Amelia Mine years ago. Their memories unfold throughout the rest of the article. We are grateful to Mike Wise and Tim Rose, geologists in the Department of Mineral Sciences at the Smithsonian.

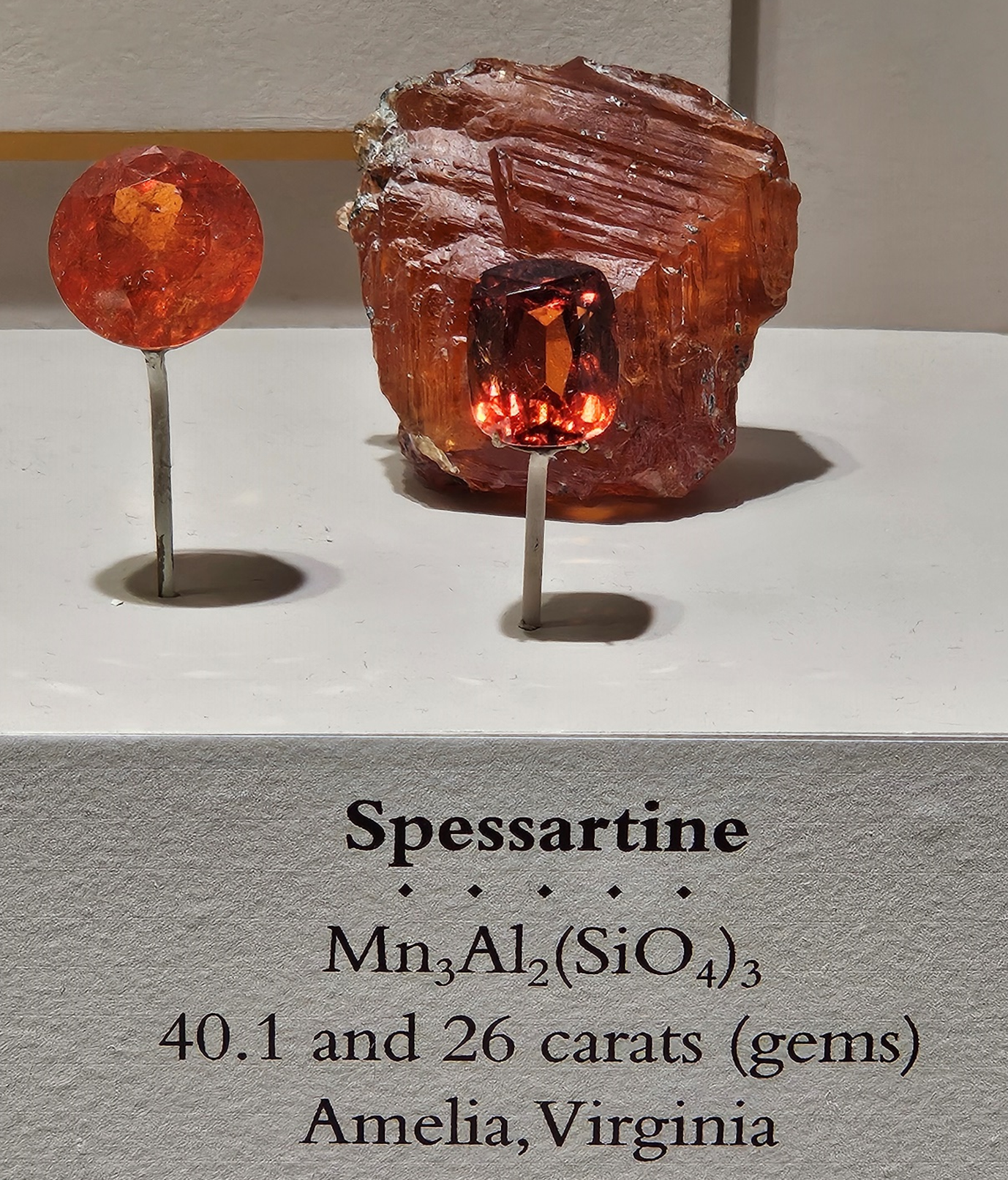

Background Info from the Morefield Mine Exhibit in the Smithsonian's Geology, Gems, & Mineral Hall

“Like many pegmatite deposits, the Morefield’s is small-only about 985 feet long and 197 feet deep. In the early 1900s, Silas V. Morefield first worked this deposit from the surface for amazonite and mica. Virginia’s Morefield Mine contains vivid bands of blue-green amazonite that glisten like a tropical sea. The Morefield Mine cuts into a pegmatite, a type of deposit characterized by large crystals of feldspar and quartz with a variety of other minerals. Morefield is mined for amazonite, used as an ornamental stone. A variety of the feldspar mineral microcline, amazonite is found only in pegmatite deposits.”

Smithsonian’s recreation of the Morefield mine, Amelia, Virginia’s pegmatite exhibit was designed by the Smithsonian’s Mike Wise and Tim Rose.

Museum Exhibit of "Pegmatite Basics"

“Minerals Matter: Members of the feldspar family in particular, microcline and albite, are the most common minerals in pegmatites. In many pegmatites, feldspar minerals are mined for use in the ceramics and glass industries and as a filler in textiles and paper.

Minerals Matter: A member of the mica family, muscovite splits, or cleaves, easily between weakly bonded layers of atoms. Because of its flexibility and insulating properties, muscovite is mined for making electrical insulators and paint fillers. Muscovite also adds sparkle to some cosmetics.”

Morefield Gem Mine in Amelia, Virginia: Tour May 30, 2015

Laura Dwyer

“In May of 2015, Kathy suggested we visit the Morefield Mine in Amelia, VA. We visited on Saturday, May 30, since it was one of the summer days when adults (with their own hardhats) were able to purchase an underground tour of the mine. We left early from Alexandria, and it was an easy drive to Amelia. Upon arrival, we put our names on a list to go underground later in the day. While we waited for the tour, we visited the gift shop and met the owner, Sam, who told us about how he had bought the mine as something fun for his retirement.

Kathy mentioned that we knew Dr. Mike Wise from the Smithsonian and that I had gone to UVA with Mike. Sam spoke fondly about Mike and about the creation of the Morefield exhibit that is in the Smithsonian. We also spent time looking through the tailings and sluice area and I especially enjoyed watching the kids having such a good time hunting for treasures.

At tour time, we signed waivers and were given safety instructions by our guide who also had worked in the mine. Going underground using the steep wooden ladder was a bit scary for me since I just do not like heights. I looked straight ahead and not down as I carefully climbed deep into the mine, gripping the ladder tightly. (I could swear it wobbled!) It was all worth it since below the surface was a wonderland of green and white. We even got a picture of Kathy and me at the same area that the guide said was reproduced in the Smithsonian's exhibit.

We were allowed to collect anything loose on the mine floor and that's where I found my nicer pieces of deep green amazonite and biotite mica. At one point, our guide picked up a white rock and handed it to me saying, "Here's a topaz" (although I suspect he was teasing and it's more likely white microcline). Going back up the ladder to exit was a bit easier than coming down. Little did we realize then how fortunate it was that we went that day since in recent years, the grounds have rarely been open to the public, let alone access to the mine. Thanks to Kathy for suggesting that trip!”

Kathy Hrechka

“I recently had the adventure of descending, down many ladders to a depth of 75 feet at the Morefield Mine on May 30, 2015. As a micromounter, I could not relate to this pegmatite, containing enormous crystals of amazonite and mica underground. I didn't need my microscope. My geologist friend, Laura Dwyer, accompanied me. We enjoyed meeting Sam and Sharon Dunaway, the current mine owners, who are enjoying retirement.” Reprinted from The Mineral Mite, June 2015.

Ken Reynolds

“I was in my first year of the mineral hobby and had seen the Morefield Mine display at the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. It was the weekend and I thought it would be fun to drive down and check it out. The drive was a little further than I had anticipated but I finally made it to the mine after driving for about 2 & 1/2 hours from Arlington. Upon arriving I discovered it was much more oriented towards children, they had a long sluice box that the kids and adults could clean their finds in hope of finding chunks of the beautiful blue amazonite, topaz, mica, and amethyst.

I later learned that the amethyst was salted and not natural to the mine, but the kids enjoyed it! I was a little disappointed and after about an hour of collecting, I was ready to head home. Fortunately, I stopped in the gift shop where I picked up a really nice piece of amazonite and a couple of Michigan copper pieces that the owner, Sam, had for sale.

I was about to leave when I saw Kathy Hrechka, a Northern Virginia Mineral Club member, and a friend of hers. They both had hard hats and lights on their heads. I quickly asked where they were going, and Kathy told me they were going underground to see the mine! My eyes lit up and I quickly asked if I could tag along?

Kathy checked with Sam, the mine owner, and got permission. The next thing I remember was climbing down a series of ladders and soon we were about 60 feet underground. The tunnels weren't very big but there were some bigger areas that were much more open. Our tour guide showed us all the minerals still in the wall and explained to us what everything was. There were large blue areas mixed with the white feldspar and brown mica. He told us there was also topaz to be found, but it was very rare.

I think we were underground for over an hour and got to see many of the tunnels. At the end of one of the tunnels we were able to pick up some minerals to take home! All in all, it was a wonderful day and one I will always remember! I always thanked Kathy and her friend Laura Dwyer because they were the only reason I got to go underground, and I will always be grateful!!!”

Mike Kaas (from a visit prior to 2015)

“I had the opportunity to visit the Morefield Mine in the early 2000s with a fellow mining engineering classmate of mine, Stan Suboleski, who lives in Midlothian, Texas. Although I had met Sam Dunaway years ago when he was with the Office of Surface Mining, Reclamation, and Enforcement (OSMRE) in Alaska, he probably did not remember me from Adam. Stan was on the faculty at Virginia Tech at one time and I believe Sam was a Tech mining engineering graduate. So, they had a strong Virginia Tech connection.

Sam was a super host, and we were able to get down into the workings and see the pegmatite and the unique geology up close and personal. It was a real thrill for me because I first got interested in minerals and earth science as a kid banging around pegmatites in Maine. In those days, feldspar was the main product for use as the abrasive in kitchen cleanser. But the government was very interested in the rare pegmatite minerals like columbite and tantalite for defense purposes during those days in the 1950s.

As a long-time Smithsonian volunteer, one thing that really impressed me was how closely the Morefield Pegmatite exhibit at the Natural History Museum matched what we observed underground with Sam. That authenticity is a tribute to Mike Wise, Tim Rose, and their colleagues at the Smithsonian”.