87 Years in 60 Minutes: Transforming an Accumulation into a Collection, presented by Gene Meieran

Synopsis by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

As an introduction, Gene said he could summarize his talk about his 87 years in a few seconds. He did that by saying: “I collect rocks. Any questions?” Getting only chuckles in response, Gene embarked on his PowerPoint presentation which interlayered images of gorgeous crystals, personal stories, and key friendships which changed his understanding of mineral collecting. All that, along with answering questions from his MSDC audience, kept everyone happily spellbound for a little over an hour.

Readers: The purpose of this report is to encourage you to check out the YouTube video of Gene’s presentation. There you will hear his extraordinary stories, see photos of his beautiful minerals, learn about his international travels and life-changing friendships. To watch the video, click here.

Gene’s slide presentation illustrated the story of how, over five decades, he gained certain insights from visiting museums and from his friends which eventually enabled him to transform his “accumulation” of rocks and minerals into a well-organized and focused “collection.”

Here is a thumbnail sketch of key road-markers in Gene’s life-long journey:

· Began collecting at age 10 in the US and Norway (1947)

· Undergrad years at Purdue University (1955-1959)

· Accumulation of minerals during his Harvard and MIT years (1959-1963)

· Accumulation slowly transformed into a collection (1978-2024)

His Journey Starts at Age 10 (1947)

Gene said his first field collecting trip was in 1945, when he was about 9. It took him from his birthplace of Cleveland, Ohio to Petoskey, Michigan to gather its fossils for which the area is well known. Of the Petoskey stone shown below, he said: “It was a neat thing for a kid to find.”

Gene explained that back then he did not do much to follow up on his first Petoskey collecting trip. But “the Petoskey stone got me started on a journey where I collected minerals” like the three shown below.

His native area of Cleveland was rich in shale and sandstone specimens which he accumulated during this first part of his life-long journey. He quipped that his initial journey toward becoming a mineral collector was fueled in part by his childhood imagination that a local shale cave contained giant quartz crystals.

The sandstone he collected during his youth, such as the tan colored specimen above, decades later became integral to his work as an adult at Intel. He had risen through the Intel ranks and became in charge of finding the materials that went into the fabrication of semiconductors. For readers to learn this personal story and how a form of sandstone was central to the semiconductor industry and to Moore’s Law, watch the video of Gene’s presentation. There you will discover how he connected the dots between his early collecting of minerals and his later work with semiconductors.

Gene shared that the impetus for his early childhood journey toward becoming a collector was significantly fostered by the arrival of his tech-oriented Uncle Sigmund who came from Norway to visit with relatives in Toronto in 1940. “He was something like an electrical engineer and had a great love for hiking and for all things outdoors.”

After WWII, Gene’s family visited their relatives in Norway. There, his Uncle Sigmund had a friend, Gunnar Henningsmoen, who was the head of paleontology for the Natural History Museum in Oslo. As a result, Gene as a 10- or 11-year-old frequented the Museum where he first encountered and was very, very impressed at his first sight of a T-Rex – “I was hooked.” This led to mineral collecting field trips which also paved the way to Gene’s love for the outdoors and collecting.

Looking back over the seven or so decades since that visit, Gene contrasted the “then” and “now” for collecting silver specimens from the famous Kongsberg mining region in the late 1940s. Below on the left is a silver specimen given him by his adult friend Gunnar Henningsmoen. On the right, is an example of the local silver wire specimens which at the time were abundant and inexpensive. However, as a child, they were beyond his means. So today Gene is keenly aware of what he might have obtained but did not, as indicated by the specimens shown below.

To underscore this story, Gene told us about a famous knowledgeable mineral dealer who, at that time, agreed to buy a metric ton of Kongsberg silver wire specimens that he was offered for $28,000. But then, the would-be purchaser was not able to pay, which resulted in the owner smelting down the entire lot. “That amount of silver wire specimens which could have been bought for $28,000 back then, would probably be worth a billion dollars today, if not more. A lot of great specimens disappeared.”

Back home in the United States, Gene in 1951 went on a collecting trip to Ohio and found a number of fine gypsum specimens and also brought home something extra that he had not intended, as noted in the above slide.

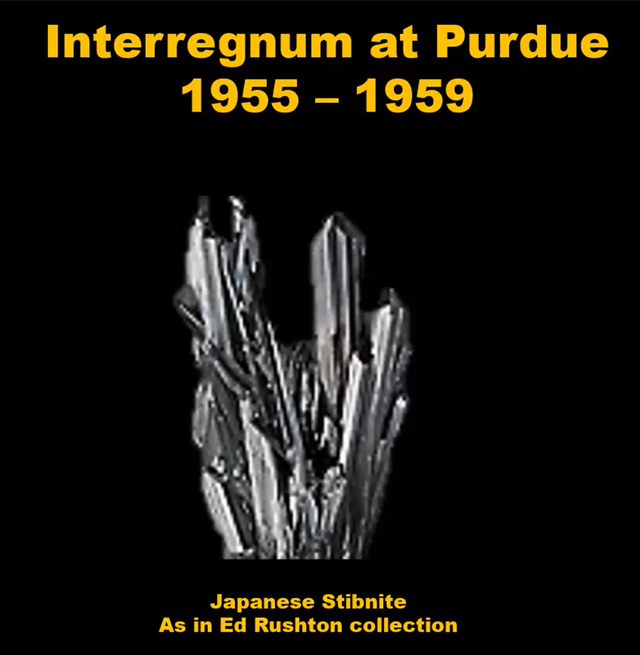

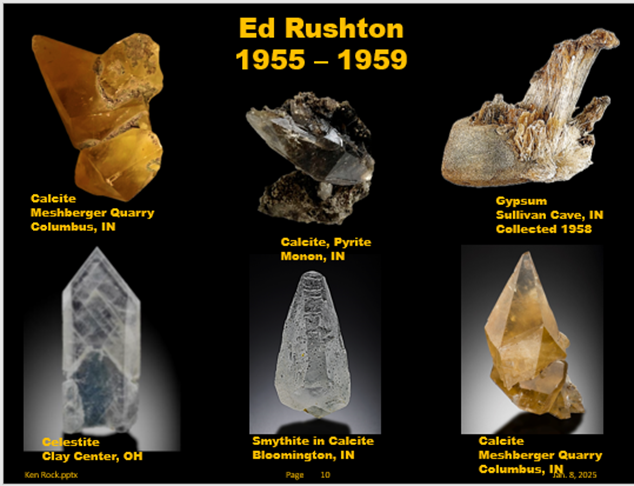

Gene’s Undergrad Years at Purdue University (1955-1959)

Gene’s next phase of collecting was marked by meeting a 19-year-old extraordinary collector and mineral dealer named Ed Rushton. Ed’s knowledge of minerals and his extraordinary collection opened Gene’s eyes. As an example, Gene recounted Ed’s explanation about the mineral composition of the smythite in the calcite crystal shown below in the middle of the bottom row. Go to the video to learn what Gene found so interesting about this extremely rare iron sulfide specimen which, Gene said, “had a big influence later on.”

Because Ed knew so many great collecting locations, the two together went on field trips that furthered Gene’s knowledge of mineralogy and his accumulation of minerals.

Real Accumulation of Minerals Started During his Harvard and MIT Years (1959-1963)

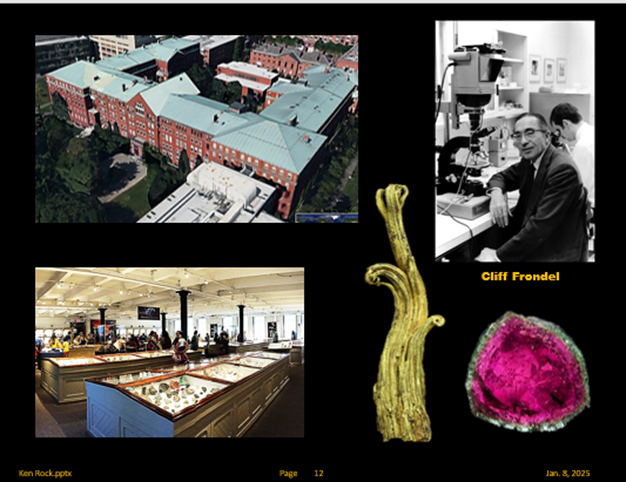

Gene’s “real collecting” started during his years at MIT located close to the Harvard mineral museum. “So I started going there a lot and saw a lot of really tremendously fine specimens.”

During the summer of 1960, Gene took a job in California which gave him access to several collecting locations including the Crestmore Quarry and the city of Boron which were where three of the minerals shown above were found. Those two sites are no longer available to collectors.

By listening to the video, viewers will learn the stories behind the other four minerals shown above and their respective collecting sites. During that summer and thereafter Gene met many additional collectors, traded to expand his collection, and learned a great deal about minerals and collecting sites.

His visits to the Harvard mineral museum, with their marvelous displays and minerals, were particularly important. Specimens included the golden horn and slice of watermelon tourmaline shown above. While visiting the museum, Gene met and spent time with the curator, a professor of mineralogy, Cliff Frondel. What made their conversations particularly interesting was that Gene had collected a rare smythite mineral from Indiana and Harvard had none. Readers will want to view the video to learn what minerals Gene traded in exchange for several smythite specimens he gave to the Harvard museum.

Each of the four minerals above illustrates the ways Gene obtained new specimens: field collecting, buying, trading, and receiving as a gift.

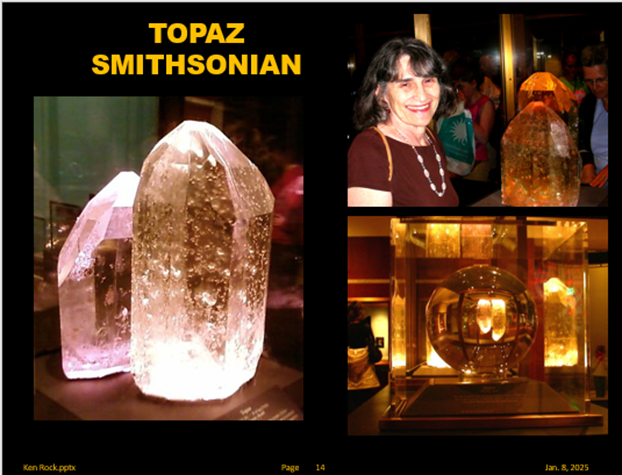

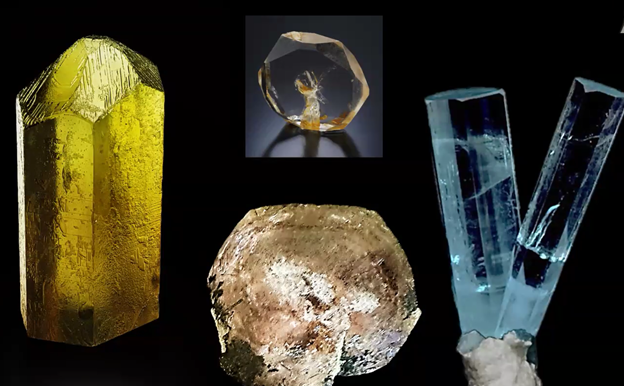

During his three years of doctoral studies at MIT, Gene worked with X-ray diffraction equipment which a nearby corporation allowed him to use for his research. That is when he encountered the extraordinarily large topaz specimens shown above which Gene rescued from destruction. He described himself as a 21-year-old student confronting the highly esteemed CEO of the manufacturing corporation. That verbal exchange resulted eventually in the two giant topaz crystals being donated to the Smithsonian where they are on display to this day. Several MSDC members were very familiar with the topaz specimens and that generated an interesting discussion. A third crystal went to Harvard.

During his three years visiting with that corporation, Gene developed his life-long interest in single cell crystals. That had implications not only for his mineral collecting but also years later for his decades-long scientific work with Intel.

Upon graduation from MIT, because of Gene’s work with single cell crystals, he decided to go with Fairchild and the semiconductor industry rather than with nuclear development. That gave him access to new collecting sites near the San Francisco Bay which yielded some of the above finds. During those years, he traveled and studied in Israel which also led to further finds, such as the above bottom right turquoise from the Sinai Dessert. “It was probably worth 25 cents then and it is probably worth 25 cents now. But it was self-collected turquoise.”

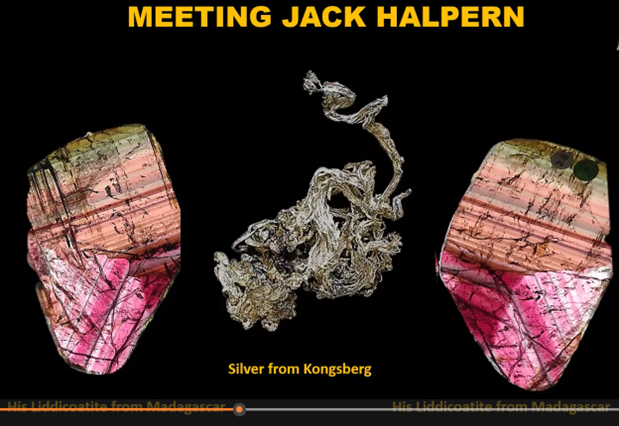

It was during this time in the Bay Area, Gene recalled “the fateful day” when he met the legendary collector Jack Halpern. The occasion was a garage sale Gene held featuring some Brazilian aquamarines he had acquired while visiting his brother in South America. This total stranger showed up and found Gene’s specimens uninteresting. But Jack realized Gene knew a fair bit about minerals. So he invited Gene to visit his house nearby and showed Gene his extensive collection.

The display which caught Gene’s eye was the case of Kongsberg specimens which included the two Madagascar liddicoatite specimens and Denmark Kongsberg silver wire specimen shown below. That area of Denmark was where Gene’s father grew up and where Gene visited as a 10-year-old.

The beauty of Halpert’s collection was so great that Gene decided then and there to no longer collect any mineral specimen that had a chemical formula and was not nailed down. That approach had allowed Gene’s collection to grow to about 1,400 or 1,500 specimens which, he said, no one else would look at. “I changed the thread of how I was going to collect.”

Accumulation Became a Collection (1978-2024)

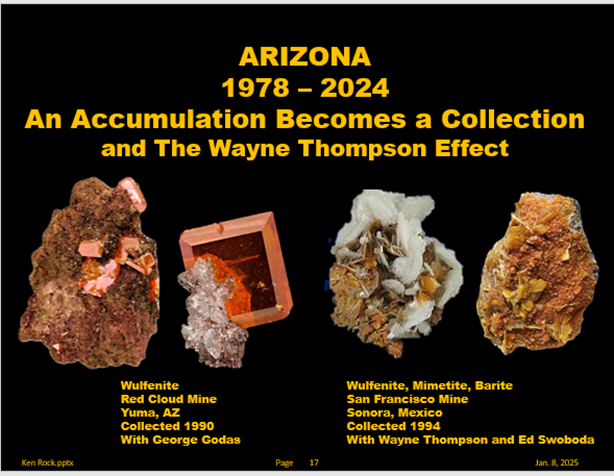

A fourth phase of Gene’s journey toward becoming a focused collector came with his move to Arizona when a started his work with Intel. He noted that he lived in Arizona only until 2009. There, Gene encountered two “effects,” the Wayne Thompson effect and the Rob Lavinsky effect, both of whom specialized in collecting rare and beautiful specimens.

To experience how their focus on rare specimens changed Gene’s collecting, readers will want to view the YouTube video in its entirety. There you will hear how, in his early thirties at the Tucson show, Gene initially met, but dismissed, Wayne as a no-nothing collector. But as it turned out, Gene said, Wayne was the one who “really got me into the single crystal world.” Together the two men shared many collecting adventures and their collaboration resulted in donations of special crystals to several major museums.

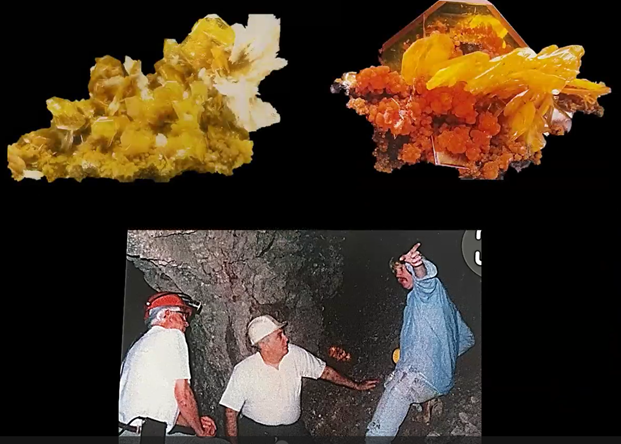

The above photo is of Gene with Wayne in the San Francisco mine and above the mine photo are two of the primary minerals they collected there.

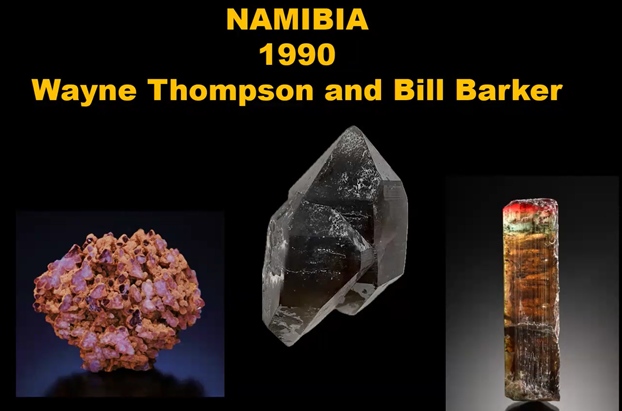

The above specimens of quartz and tourmaline Gene and Wayne found in a mine in Namibia.

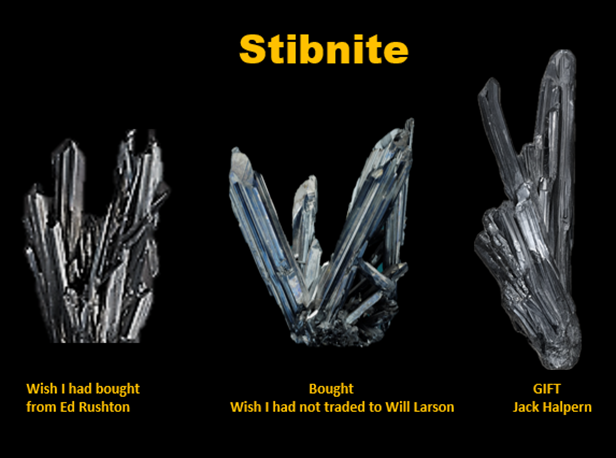

In the years following, Gene continued to focus on single cell stibnite crystals such as those shown above.

With those years and reflections also came the realization of the specimens that got away, such as those pictured below. Each of those lost opportunities has its own story and associations with collecting sites and a network of friends. Those regrets and missed opportunities, Gene noted, were minor compared to the guy who, for the lack of having $28,000, missed out on purchasing the Norwegian Kongsberg silver wire specimens that today would be worth billions.

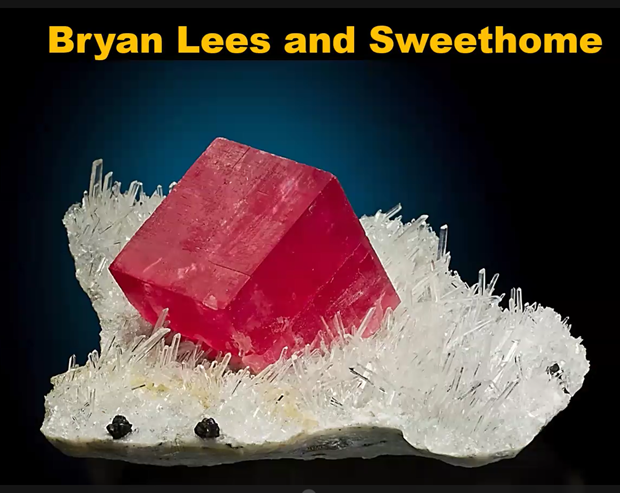

“I’ve tried to share with you the two things that changed my life, the museums and their specimens, and the people that I was associated with during my trips through the mineral world” as I traveled and collected around the globe. As an example, he talked about his meeting with Bryan Lees of the Sweet Home Mine in Colorado. That gathering resulted in Gene, Bryan, and two colleagues joining together in a project which resulted in their pulling out an extensive number of rhodochrosite specimens such as the one shown below.

With all those field trips and friendships over the years, Gene’s favorite minerals continue to be the Kongsberg silver wire specimens. They harken back to his early field trip as a 10-year old to his paternal homeland in Denmark. Remembering that first international field trip and those that followed, he said, they all were wonderful to be part of.

Looking back over the decades, Gene also recalled his experiences with technology. One of the true founders of Fairchild Semiconductor and Intel was Gordon Moore, shown with Gene below.

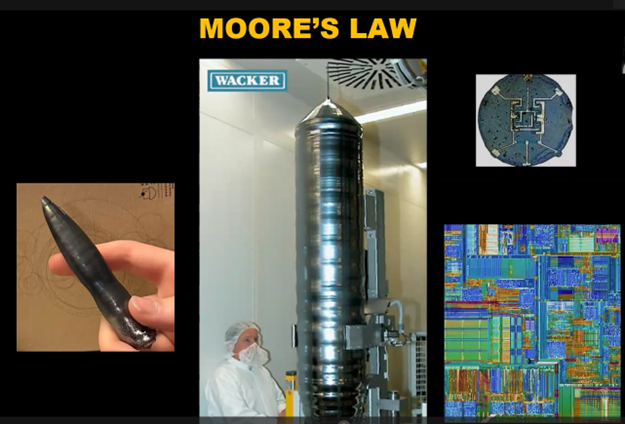

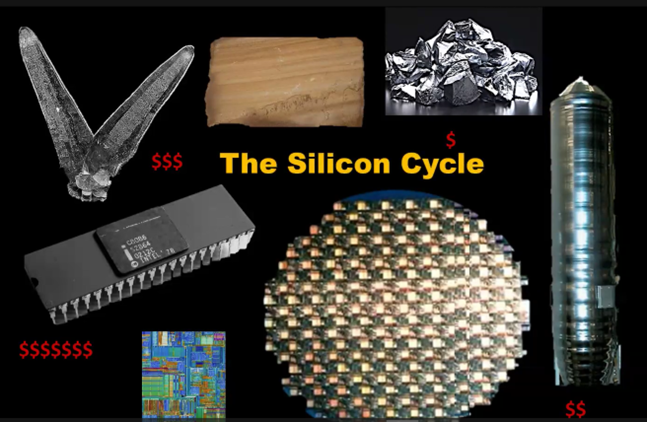

Readers who view the YouTube video, if they do not already know, will learn about how Moore’s law affirmed that the complexity of a chip doubled every generation (about 18-months). As shown below, the size of the silicon wafers evolved from initially being about the size of a finger on the left, into the large silver silo’s size in the center. The progress in size was matched by the drive to produce larger and ever more defect-free crystal lattice structures.

During his decade with Fairchild and his subsequent decades with Intel, Gene said he observed that the cost of minerals followed a similar upward trajectory as did the evolution of the semiconductors.

Gene then turned his attention to the “second effect,” mentioned above, the Rob Lavinsky effect. Gene credited Rob, along with Wayne Thompson, with changing his collecting in the direction of collecting rare and beautiful specimens. This is the story about what Gene called “a change in life.”

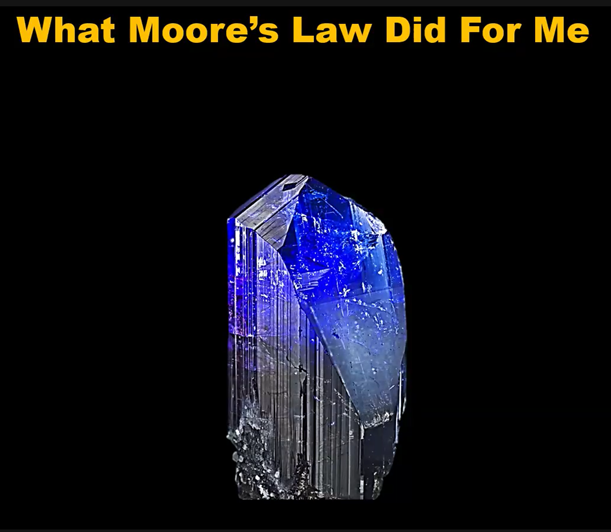

Before meeting Rob, Gene owned about 1,500 very diverse minerals, only a few of which, such as his Kongsberg silver specimens, were of interest to other collectors. As a result, of the two effects, Gene said: “I traded all of them, about 1,200 specimens, for the one tanzanite” shown below.

The increased value of the Intel transistors, described by Moore’s law, enabled this transition to focusing on collecting more beautiful crystals, including those below.

To learn about each of these large and beautiful single cell crystals, where they originated and how Gene obtained them, go to the YouTube video. There you will also learn the characteristics of what Gene’s ideal crystal looks like. Hint: it is the smallest of the four minerals shown below.

Readers will not want to miss Gene’s explanation of the transformation of minerals which is the basis for Moore’s law and how the increased purity of the semiconductors evolved and enabled the complexity and efficiency of the advanced integrated circuits.

As shown below, it begins with the sandstone quartz silica that he found in Cleveland as a child. Refine it into metallic pure polysilica. Grow that defect free into the large silicon crystals. Turn that in the slices of silicon wafers which are then made into integrated circuits and high-tech electronic packages. This purification process is illustrated by following the clockwise circuit shown below. For Gene, it culminates in the ability to obtain beautiful crystals.

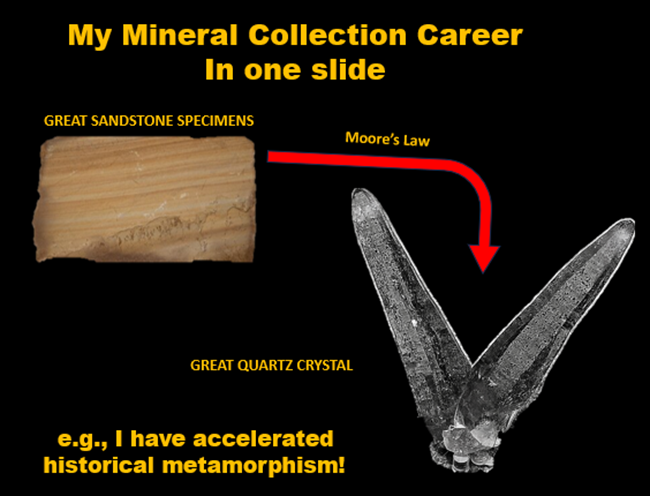

In conclusion, Gene quipped: “I came from Cleveland and, validated by Moore’s law, I turned sandstone into quartz” as illustrated in the slide below. He added: “You know it took the Earth a long time to do that. I did that in the space of forty years.”

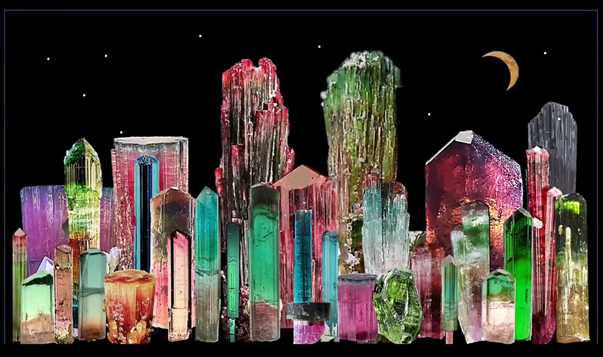

As an extra feature, Gene recounted that he happened to be looking at the skyscape of New York City and for fun decided to arrange some of his crystals and photo shop them to mimic the NYC skyscape, shown here as bookends to Gene’s talk, at the beginning of this report and here below, at its conclusion.

MSDC’s president Dan Teich then thanked Gene for his superb presentation and opened the floor to questions and answers from his listeners. The audience with strong applause signaled their great appreciation for Gene’s marvelously crafted presentation that, like the semiconductors with which he worked, he delivered without flaws or imperfections. We encourage all readers to watch the YouTube video of Gene’s presentation.