A Stunning Gem, to Honor a Slain Geologist, Unveiled at Smithsonian

Discoverer of a beautiful green mineral was slain in Kenya by robbers 14 years ago

By Michael E. Ruane, The Washington Post, April 19, 2023. Used with permission of the author.

The jewel rested on a cushion in a small black box covered with cloth in a vault at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Jeffrey Post, curator of the National Gem and Mineral Collection, put on a pair of white cotton gloves, pulled off the cloth and opened the box. “So, this is the stone,” he said, holding it under the fluorescent lights — a lustrous, green 116-carat gem called a tsavorite.

With 177 facets, it glittered as he held it. “It’s truly a beautiful stone,” he said. “When you look at the color of it, it just doesn’t look like anything else that we have.” Technically a garnet, it is named the Lion of Merelani. And, as with many a precious gem, it comes with a story.

On Thursday (April 20, 2023), the Smithsonian plans to unveil the gem — named in part for the Merelani region of Tanzania where it was found — and display it along with the Hope Diamond, the Carmen Lúcia ruby and other spectacular jewels in its hall of geology, gems and minerals.

It is the largest precision-cut tsavorite in the world, the museum says. It arrived at the Smithsonian late last year.

The museum said the stone, which was found in 2017 and cut over three months by renowned gem cutter Victor Tuzlukov, was donated by Somewhere in the Rainbow, a private gem and jewelry collection, and by tsavorite mining executive Bruce Bridges, in honor of his late father.

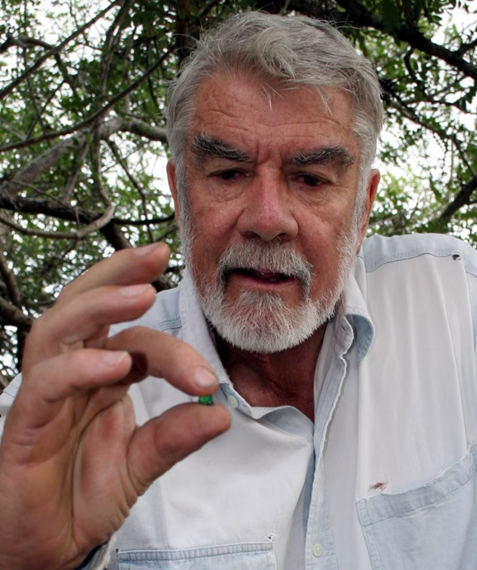

Bridges’s father, geologist Campbell Bridges, discovered tsavorite in East Africa in the 1960s — reportedly while fleeing from an angry buffalo — and brought it to prominence. He had lived most of his life in Africa, often in a treehouse near his mines, and was known as the old lion.

But in 2009, he was murdered in Kenya by a gang of illegal prospectors who had been threatening him and trying to drive him away from his mines, his son said in an interview. On August 11, they ambushed him, his son and four of their employees, and stabbed the elder Bridges to death. “Losing my father is the worst tragedy in the history of our family,” Bruce Bridges said. “And the driving forces in our lives have been to seek justice … and then on top of that to ensure that my father’s dream and legacy for tsavorite lives on.”

“What better way than to have all of this come full circle and have this particular, one-of-a-kind tsavorite in the National Gem Collection,” he said.

Campbell Bridges had a long relationship with the Smithsonian that began in 1967, when he traded some of his tanzanite specimens to the museum for some of its tourmaline collection, Bruce Bridges said. The younger Bridges said he was a child when he met Post, the curator. Bruce Bridges said he bought the “rough” or uncut version of the stone, declining to say what he paid for it. “I might never see or have possession of such a gem again,” he said in a telephone interview Tuesday. He said it could easily be sold, but then few would enjoy its beauty. “I felt such a historical piece needed to be shared with the world,” he said. He said he believed his father would be overjoyed by the donation. “I can’t really think of a much better ending for the journey and story of this gem.”

The “lion,” roughly the size of a quarter, is giant by tsavorite standards, said Gabriela A. Farfan, a Smithsonian curator of gems and minerals. “Usually they’re quite small,” she said in an interview at the museum last week. “They’re like the size of a pinkie nail. That would be considered a large stone already. And so this is huge.” “Take a look at those facets,” she said. “Look up closely. Look how perfect they are.” The gem is hypnotic, a miniature green hall of mirrors. And its rectangular “cushion” shape makes it especially rare, Bruce Bridges said. Its worth has yet to be determined, Post said. “All we can say is: It’s one of the great gemstones that’s come out in recent years.”

He and Farfan said they first saw the gem in 2020 at a gem and mineral show in Tucson. They said they were told they would be shown something very special. People “were being very hush-hush about it,” Farfan said. “It’s so valuable,” she said. “You don’t want the world knowing that you have a very valuable stone on you. We were very lucky we were representing the Smithsonian. People will sometimes show us their extra special things.” “It was very secretive,” she said. “All of us crowded around it.” Bruce Bridges “unveiled it, and all of us were like, ‘Wow.’”

Post said they had no idea that the extraordinary stone would ever come to the museum. But “where do you put something special where anybody can see it?” Post said. “The Smithsonian is the place. … Anybody in the world can walk in our front door free of charge.”

Post pointed out that James Smithson, the Smithsonian’s founding donor, was a mineralogist, whose collection came to the institution. The mineral, Smithsonite, is named for him. His collection was destroyed in 1865 by a devastating fire in what is now the Smithsonian Castle building. “So we basically started over again,” Post said.