Benjamin Franklin's Use of Mica and Graphite to Fight Counterfeiters

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

Benjamin Franklin may be best known as the creator of bifocals and the lightning rod, but a group of University of Notre Dame researchers suggest he should also be known for his innovative ways of literally making money.

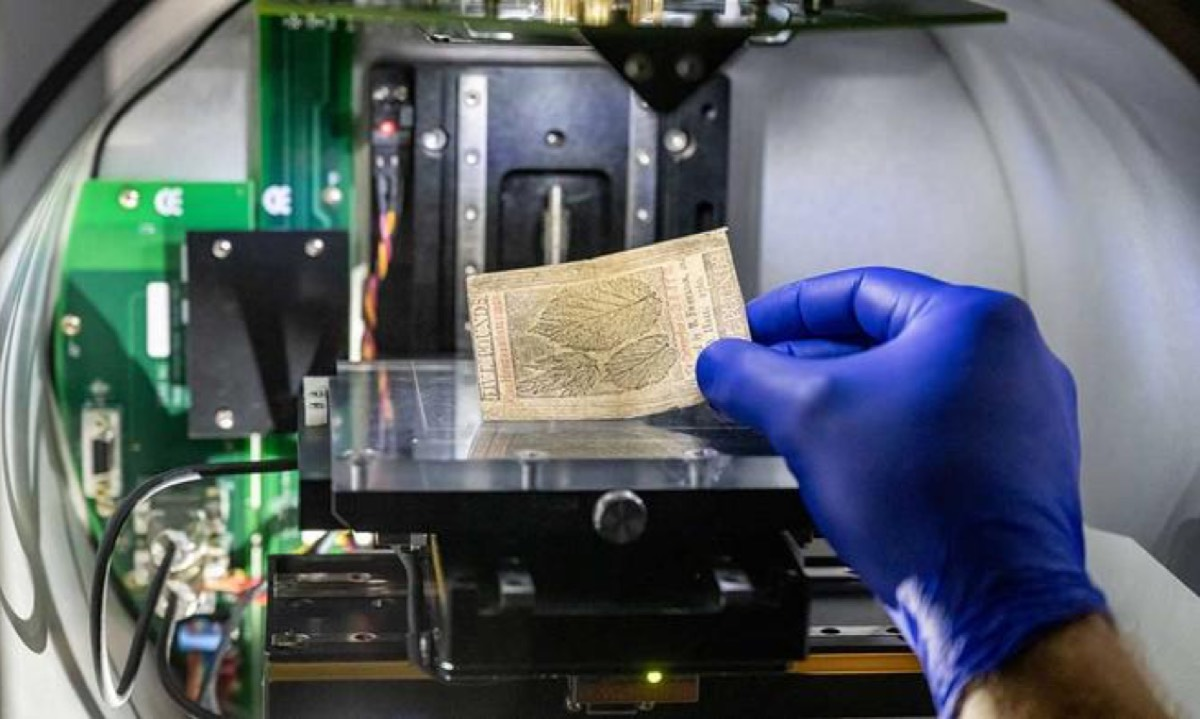

During his career, Franklin printed nearly 2,500,000 money notes for the American Colonies using what the researchers have identified as highly original techniques, as reported in a July study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS). Franklin’s bills “served as an archetype for printed money” to come, says Khachatur Manukyan, a physical chemist at the University of Notre Dame and author of the NAS study. “It was very sophisticated for that time.”

The Beginning of Paper Money in the Colonies

When Benjamin Franklin moved to Philadelphia in 1723, he got to witness the beginning of a risky new experiment: Pennsylvania had just begun printing words on paper and calling it money. To staunch the flow of metal coins from the 13 colonies to England as payment for imported goods, several colonies began printing bits of paper to stand in for coins, stating that within a certain time period, they could be used locally as currency. The system worked, but haltingly, the colonies soon discovered. Print too many bills, and the money became worthless. And counterfeiters often found the bills easy to copy, devaluing the real stuff with a flood of fakes.

Franklin, who started his career as a printer, was an inveterate inventor who found paper money fascinating and experimented with printing techniques as he worked on securing colonial printed currency. In 1731, he won the contract to print £40,000 for the colony of Pennsylvania and he applied his penchant for innovation to currency.

Franklin recognized the need for American paper money to break American dependence on the British trading system and he helped print Continental money to finance the War of Independence. During his printing career, Franklin produced a stream of baroque, often beautiful money.

Recent Research Results

In the July 2023 NAS study, a team of physicists revealed new details about the composition of the ink and paper that Franklin used, raising questions about which of his innovations were intended as defenses against counterfeiting and which were simply experiments with new printing techniques.

The study drew on more than 600 artifacts held by the University of Notre Dame, said Manukyan. He and his colleagues looked at 18th-century American currency using a unique combination of advanced atomic-level imaging methods, including Raman spectroscopy, which uses a laser beam to identify specific substances like silicon or lead based on their vibration. They also used a variety of microscopy techniques such as such as infrared, electron energy loss spectroscopy, and X-ray analysis, to examine the paper on which the money was printed.

Mica & Colored Threads

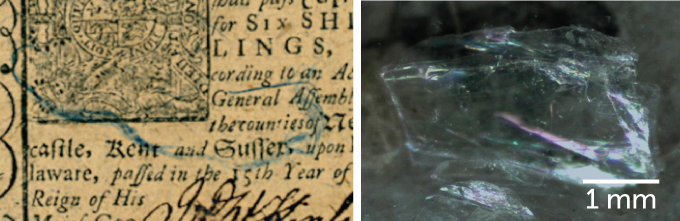

The advanced imaging methods allowed the researchers to see features such as colored threads and muscovite incorporated into the paper. The blue threads are visible to the naked eye, and the muscovite produces a glimmer that reflects light, features most knock-offs wouldn’t have been able to reproduce.

These shiny patches were most likely an attempt to combat counterfeiters, who would not have had access to this special paper, said Jessica Linker, a professor of American history at Northeastern University who studies paper money of this era and was not involved in the study. Of course, that didn’t stop counterfeiters from trying. “They came up with very good counterfeits, with mica pasted to the surface,” Dr. Linker said.

The Philadelphia area is notable for its schist, a course-grained metamorphic rock that contains mica. It’s possible that Franklin or printers and papermakers associated with him collected the substance used in their paper locally, Dr. Manukyan said. The mineral was also probably used to increase the durability of the notes so they could hold up better during circulation.

The muscovite, found in about 95 percent of the analyzed Franklin bills produced after 1754, was probably sourced from the same geologic area, the team says, suggesting that a single mill produced the paper.

Graphite

It's known that Franklin made his own inks. The analyses revealed that he used a mercury sulfide red ink, as well as bone black ink, made from carbonized animal bones. However, his own personal mixed inks seem to have been pure graphite.

X-ray analysis of British paper copies showed the phosphorus and calcium signatures of bone black ink, but Franklin's original banknotes don't have that signature. When the scientists examined the black ink on some of the bills, they were surprised to find that it appeared to contain graphite. For most printing jobs, Franklin typically used black ink made from burned vegetable oils, known as lampblack, said James Green, librarian emeritus of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Graphite would have been hard to find, he suspects.

“So Franklin’s use of graphite in money printing is very surprising, and his use on bills printed as early as 1734 is even more surprising,” Mr. Green said in an email.

Could using graphite ink have been a way to differentiate real money from fakes? Differences in color between graphite and lampblack are likely to have been subtle enough to make that a difficult task, Mr. Green said. Instead, we may be looking at another example of Franklin’s creativity.

“It suggests to me that almost from the start he was using his money printing contracts as an opportunity to experiment with an array of new printing techniques,” he said.

Intricate Designs

Franklin created a copper plate of a sage leaf to print on money to foil counterfeiters. The intricate structure of the leaves was detailed enough so that one could make out the traces of their veins. The intricate pattern of veins could not easily be imitated. This method of "nature printing" was first used by Leonardo da Vinci, according to the study's authors. Franklin influenced a number of other printers as he experimented with, and produced, new paper and concocting inks.

Efforts to thwart counterfeiters of early American money were eventually upended by the British, who had figured out some of the techniques when they flooded their upstart colony with fake bills as a destabilizing tactic during the American Revolution. The value of American money tanked, and in the years following the revolution, the U.S. government shunned paper bills for decades in favor of coins. It didn't reconsider paper money until the onset of the Civil War in 1861, when the federal government first authorized the printing of dollar bills called "greenbacks."

Analogs in Modern Currency

The colored threads used in those early U.S. banknotes remain in use today, albeit in a more modern form. Today's U.S. currency features not only blue and red security threads embedded throughout, but also additional anti-counterfeiting features such as raised printing from the intaglio printing process used, color-shifting inks, a watermark, and a 3-D security ribbon that is woven into the paper, not printed on it.

In denominations $5 and higher, our currency also features a thin, vertically oriented security thread that fluoresces a different color when held to ultraviolet (UV) light. The thread is embedded in a different position for each denomination and is visible from both sides of the note.

Finally, our modern U.S. currency also includes a feature that serves the same purpose as the fine lines shown in the veins of the leaves in some of Franklin's currency, as shown in the previous photo. The modern-day analog to those fines lines is microprinting, tiny lettering that looks like a simple line to the naked eye, but can actually be read with the use of a magnifying glass. Microprinting may be found in many different locations on a note.

Conclusion

Franklin use of natural graphite pigments to print money, his creation of durable “money paper” with colored fibers and translucent muscovite fillers, along with his own unique designs of “nature-printed” patterns and paper watermarks made early American paper currency an archetype for developing paper money for centuries to come.

Sources

1) The New York Times, Benjamin Franklin’s War on Fake Currency, by Veronique Greenwood, July 25, 2023.

2) Science News, How Benjamin Franklin Fought Money Counterfeiters by Joshua Rapp Learn, July 17, 2023.

3) Phys.org, How Benjamin Franklin laid groundwork for the US dollar by foiling early counterfeiters, by David Hamilton, July 22, 2023.