Bright Green Books from the Mid-1800s May Contain a Hidden Danger: Arsenic

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

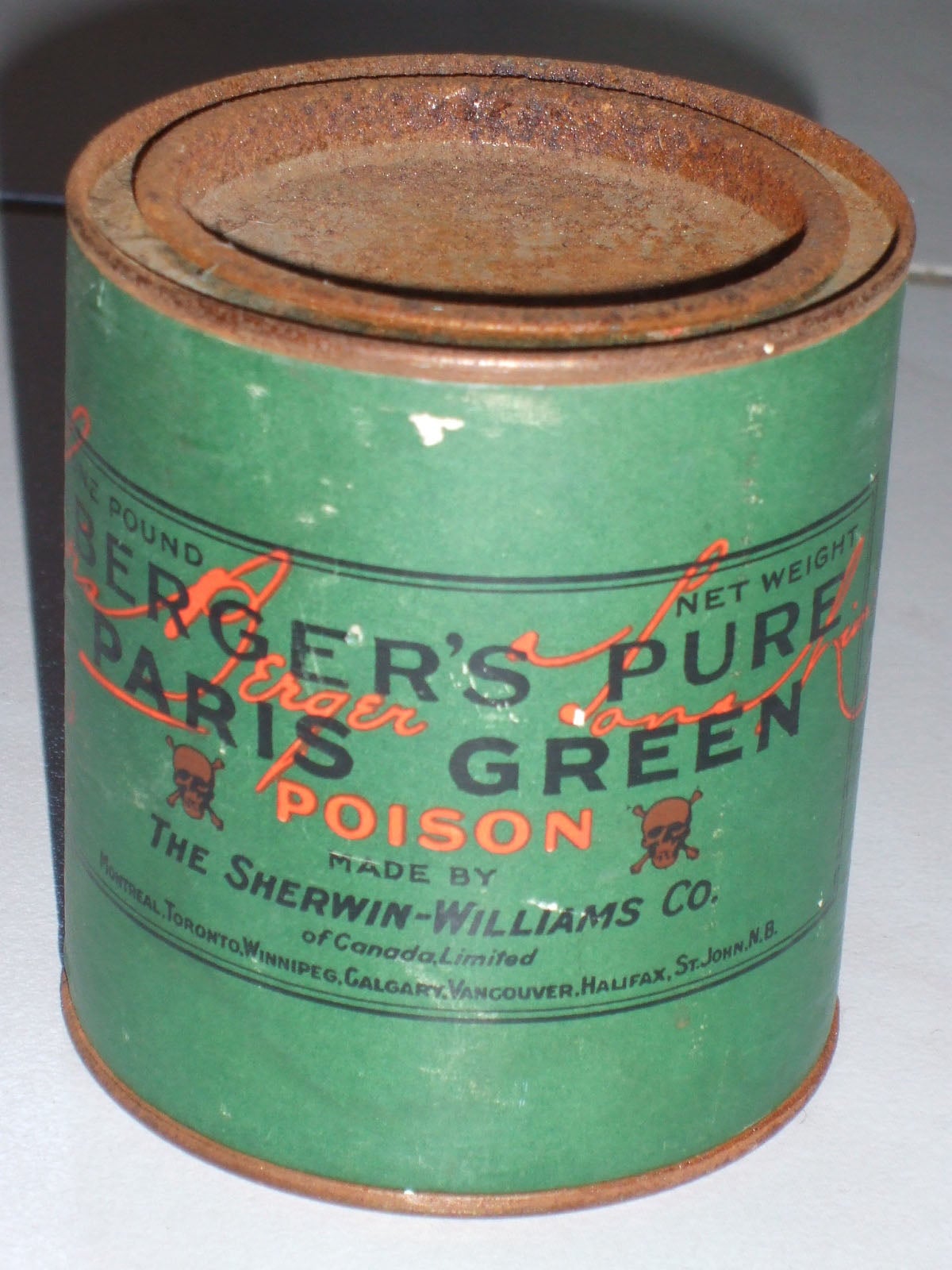

A handful of books published in the mid-19th century, bound and covered with a pigment known as emerald green, are both rare and potentially deadly. Emerald green, also known as Paris green, is the product of combining copper acetate with arsenic trioxide, producing copper acetoarsenite. The green arsenic-containing pigment found on the book covers is named because of its eye-catching green shades, similar to those of the popular gemstone.

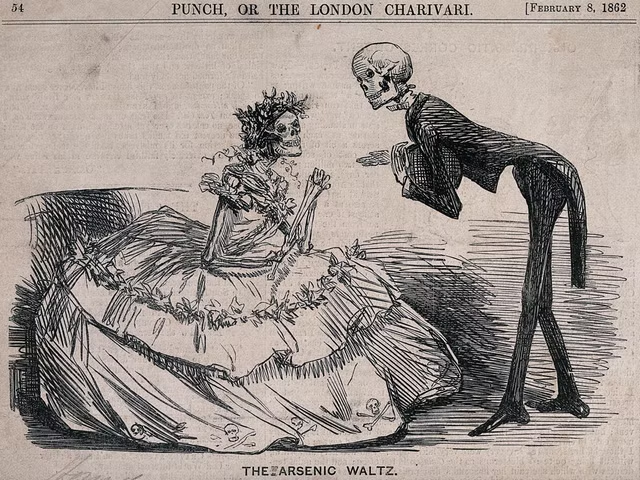

Prior to, but particularly during the Victorian era, the use of arsenic was surprisingly commonplace. Hyperallergic’s Allison Meier reports that in addition to acting as a key ingredient in green paint and dye, the pigment was used in cosmetics, children’s toys and wallpaper. The Telegraph’s Lucinda Hawksley adds that individuals even ate vegetables sprayed with arsenic-laced insecticides, or meat dipped in the poison in an effort to stave off flies.

Characteristics of Arsenic

Arsenic (As) is a ubiquitous naturally occurring metalloid. In nature, arsenic is typically combined with other elements such as carbon and hydrogen. This is known as organic arsenic. Inorganic arsenic, which may occur in a pure metallic form as well as in compounds, is the more harmful variant.

The toxicity of arsenic does not diminish with time. Arsenic is among the most toxic substances in the world and exposure may lead to various symptoms of poisoning, the development of cancer and even death. Depending on the type and duration of exposure, symptoms of arsenic poisoning include an irritated stomach, irritated intestines, nausea, diarrhea, skin changes and irritation of the lungs.

The toxic pigment was commercially developed in 1814 by the Wilhelm Dye and White Lead Company in Schweinfurt, Germany. In its heyday, all types of materials, even book covers, wallpaper, fake flowers, and clothes, could be coated in Paris green for aesthetic reasons. Impressionist and post-impressionist painters used different versions of the pigment to create their vivid masterpieces. This means that many museum pieces today contain arsenic.

The arsenic pigment – a crystalline powder – is easy to manufacture and was commonly used for multiple purposes, especially in the 19th century. The size of the powder grains influence on the color toning, as seen in oil paints and lacquers. Larger grains produce a distinct darker green while smaller grains produce a lighter green. The pigment is especially known for its color intensity and resistance to fading.

By the second half of the 19th century, the toxic effects of the substance were more commonly known, and the arsenic variant stopped being used as a pigment and was more frequently used as a pesticide on farmlands.

Pre-Victorian Uses of Arsenic in Books

Allie Alvis, a rare book collections cataloguer for Washington, DC book dealer Type Punch Matrix and a former special collections reference librarian at the Smithsonian Libraries, has researched books containing arsenic dating back to the 17th century.

Back then, book binders covered second-hand vellum with a pigment known as vergaut — a color made by mixing indigo and orpiment, a yellow-orange arsenic sulfide mineral. Despite salacious backstories peddled by some booksellers, Alvis says it's unlikely that these books contained toxins for nefarious or security purposes. "They weren't trying to keep people from putting their hands on these books," she recalled. "Some people speculated in the early days of our looking at these books, was it an insecticide? "No, it was just because it was green. It was just a nice color of green."

The Poison Books Project

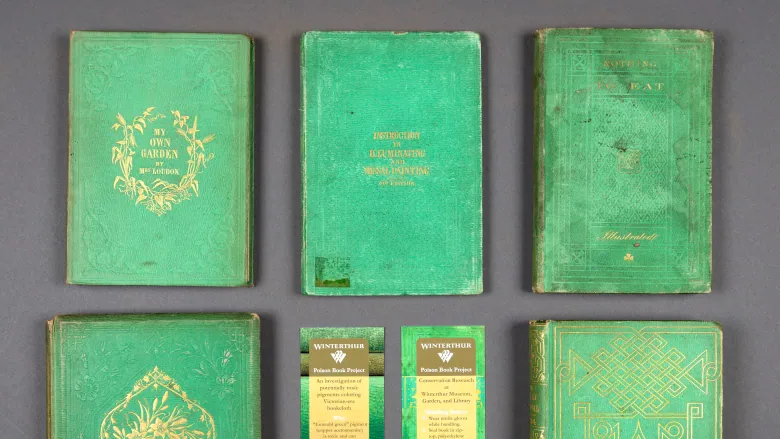

Because of a concern that many of the books containing Paris green are going unnoticed on shelves and in collections, Melissa Tedone, the lab head for library materials conservation at the Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library in Delaware, launched an effort in 2019 called the Poison Book Project to locate and catalogue these noxious volumes. The project is an ongoing investigation to explore the materiality of Victorian-era publishers’ bindings, with a focus on the identification of potentially toxic pigments used as bookcloth colorants.

Tedone first discovered arsenical pigments on book covers while examining a copy of Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste by Shirley Hibberd — a "gorgeous" book in a "sort of gaudy Victorian way," published in 1857. She was repairing the book's spine and boards when she found green pigment flaking off, which struck her as unusual. "It really seemed like the color was in a thick coating that was just on the surface of the book cloth, rather than a dye which would have penetrated the textile fibers of the book cloth and colored the fibers themselves," said Tedone.

"We're sort of following that path of looking at all the toxic components that could be in book cloth," Tendone told CBC Radio. "But then we're also trying to document all of the 19th century mass-produced book bindings that might contain any kind of arsenic in them."

"It really seemed like the color was in a thick coating that was just on the surface of the book cloth, rather than a dye which would have penetrated the textile fibers of the book cloth and colored the fibers themselves," said Tedone. The color also wasn't alone in its toxicity. Scheele's green, another popular pigment of the time, also contained arsenic, while chrome yellow was a mix of chromium and lead.

Analytical Techniques

To learn the identity of the mysterious green pigment, Tedone turned to Rosie Grayburn, head of the museum’s scientific research and analysis laboratory. Grayburn first studied the sample with an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer, which bombards material with x-rays and measures the energies of emitted photons to determine its chemical composition. This technique can tell you the elements that are present, but not how they are arranged in a molecule. Another technique using a Raman spectrophotometer measures how light from a laser interacts with target molecules, shifting the energy of the laser up or down. Much like each person has unique fingerprints, every molecule has a characteristic Raman spectrum. The sensitivity of these techniques is key, but equally important is that they are nondestructive. “You shouldn’t be damaging works of art,” Grayburn says.

X-ray fluorescence revealed the presence of both copper and arsenic in the green pigment, a key finding, and the unique fingerprint from Raman spectroscopy positively identified the pigment as the infamous emerald green.

Conservation staff and interns at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library conducted an initial survey of bookcloth pigments in the library’s circulating and rare book collections, later expanding their data set in cooperation with The Library Company of Philadelphia. The effort focused initially on books published between 1837 and 1900, a time-period which saw a growing use of commercial bookcloth on publishers' case bindings.

The first 200 books tested included a range of vivid bookcloth colors. Thereafter, only books covered in green cloth were selected for analysis, in order to focus on arsenic and move through the collection more efficiently. Now that analysis of green bindings is complete, other colors of bookcloth continue to be analyzed in stages.

Results of Testing

Nearly 350 green cloth bindings in the collections of Winterthur and The Library Company of Philadelphia were analyzed. Two books procured from second-hand booksellers were also included in the testing, and were confirmed to contain emerald green. In total, 39 green cloth bindings were found to contain arsenic. Quantitative analysis performed at the University of Delaware Soil Testing Lab indicated that emerald green bookcloth colorant is extremely friable and offsets a significantly detectable amount of arsenic.

As of the latest update on February 28, 2023, the project had identified a total of 146 books that use emerald green on their covers.

Tedone notes that not all green-covered books published in the 19th century contain arsenic, and people with older books at home shouldn't panic. "We are not aware of any cases of anyone getting seriously ill from handling a book like this," she said. "We just want to make people aware of the potential hazards so that we can avoid any tragedy ever happening from one of these books." People who believe their books may contain emerald green can request a Poison Books Project bookmark which includes a color swatch to help identify the specific shade.

Despite their potential danger, Alvis says the affected books shouldn't simply be tossed. Instead, they can offer unique insight into bookbinding techniques and practices from the past. "These are precious objects, usually even before we discovered they are arsenical," Alvis said.

"I knew about wallpapers that had arsenic pigment and I knew of book illustrations that had arsenic pigment in them, but you don't expect poison to be covering the outside of a book where you're going to hold it to read it."

-- Melissa Tedone, a conservator at Delaware's Winterthur Museum

Risks of Handling of Books Containing Paris Green

In an effort to learn more and quantify the risks, Tedone and Grayburn reached out to Michael Gladle, the director of environmental health and safety at the University of Delaware. “Arsenic is a heavy metal and does have some toxicity associated with it, principally, either inhalation or ingestion,” he says. The relative risk of emerald green bookcloth “depends on frequency,” Gladle says, and is of primary concern “for those that are in the business of preservation.”

The team next used the University of Delaware soil laboratory to measure the amount of arsenic in the covers. They found that in the first book tested, the bookcloth contained an average of 1.42 milligrams of arsenic per square centimeter. Without medical care, a lethal dose of arsenic for an adult is roughly 100 milligrams, the mass of several grains of rice.

Emerald green publishers’ bindings present a health risk to librarians, booksellers, collectors, and researchers, and should be identified, handled, and stored with caution. Although simply handling these books today is not likely to cause significant harm, acute symptoms of arsenic exposure can include gastrointestinal symptoms. Long-term effects can lead to lesions and cancer.

There are no FDA guidelines on the amount of arsenic that is deemed acceptable to handle, eat, or inhale. But fragile antique and vintage books provide possible contamination since they are handled sometimes with bare hands, which if not washed properly can lead to arsenic ingestion. But, just skin contact alone can cause a variety of health problems.

Conclusion

The Poison Book Project suggests wearing nitrile gloves when handling books that may have been painted with emerald green and storing them in isolated polyethylene bags. Known arsenic books should be handled on hard surfaces that can be washed down to avoid accidental contamination. And, the use of an air-removing ventilation system is ideal, too. Winterthur, Tedone said, now stores emerald green books in a rare books collection, away from open stacks.

Although arsenic’s toxicity was known at the time, the vibrant color was nevertheless popular and cheap to produce. Wallpapers shed toxic green dust that covered food and coated floors, and clothing colored with the pigment irritated the skin and poisoned the wearer. Despite the risks, emerald green was ingrained into Victorian life—a color to literally die for.

Editor's Note: Sources of information for this article include:

(1) Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) Radio, posted on June 4, 2022. Written by Jason Vermes. Interview with Melissa Tedone, produced by Laurie Allan.

(2) A National Geographic item, "These green books are poisonous—and one may be on a shelf near you," by Justin Brower, published April 28, 2022, and

(3) The Independent, "How three poisonous books were discovered in a University Library" by Jakob Povl Holck and Kaare Lund Rasmussen, July 5, 2018.

(4) Great Life Publishing and Greater Good, "Buyer Beware: Old Books Can Contain Deadly Arsenic, Pretty to look at, dangerous to handle" by Rose Heichelbech, 2023.