Diamond Prospecting in Murfreesboro, AR, presented by Kathy Hrechka

Synopsis by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

This report is provided to encourage readers to visit MSDC’s YouTube channel to view Kathy’s 38-minute video in its entirely at: Diamond Prospecting in Murfreesboro, Arkansas - Kathy Hrechka.

MSDC’s Vice President for Programs, Cindy Schmidtlein, introduced Kathy Hrechka, MSDC member and volunteer webmaster and editor for the Micromineralogists of the National Capital Area. Kathy also is a volunteer at the Geology, Gems, & Mineral Hall at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH).

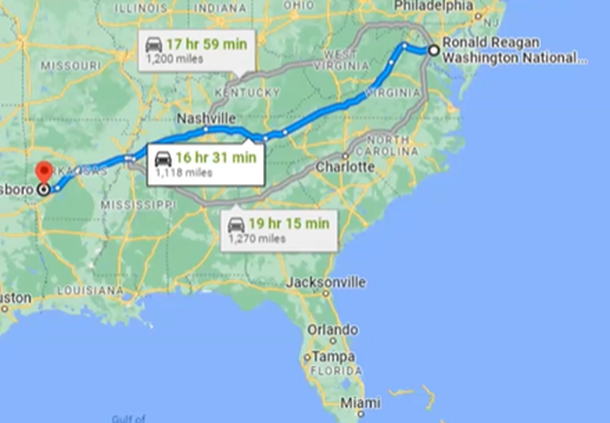

Kathy began her presentation by providing her audience with a map of the location of the diamond field she explored in Murfreesboro, Arkansas. Located near the western edge of the state, Crater of Diamonds State Park is a 37-acre site and is one of the world’s very few diamond sites that are open to the public. For a small fee, individuals can prospect and keep whatever diamonds or other minerals they discover.

Naturally occurring diamonds have been discovered at the site since 1906. Its flat fields are the eroded surface of a relatively unique lamproite volcanic rock composition which gives its diamonds their specific characteristics.

Kathy described her preparations which included studying travel options, talking with friends, reading about the site’s geological background, and reviewing information available from the Crater of Diamonds State Park website.

“So naturally I want to go on the website… to learn what kind of diamonds I am actually looking for. And, sure enough, there are very specific, very individual, very kind of melted looking” diamond specimens that visitors have been finding since 1906. Kathy noted that most of the diamonds are brown, yellow, and white, with the variations due to the site having four types of lamproite.

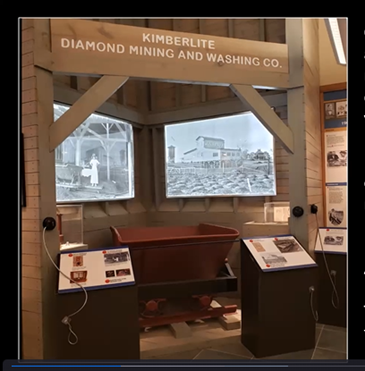

Upon arrival, Kathy found that the visitor center complex had a museum and educational center with displays describing the history of the site. The site was originally a farm and later an area that a succession of companies used to prospect for diamonds. In 1972, the area officially became an Arkansas State Park. So, Kathy’s visit in 2022 was during the 50th anniversary as a State Park. Over that half century, the State Park Service recorded that its visitors had found 35,000 diamonds.

Regional Geology

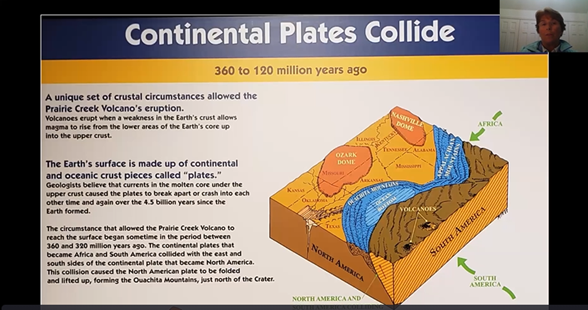

Kathy then described the unusual geology of this locale. She noted that the area was formed by the collision of three continental plates. As illustrated below, the North American, South American and African plates crashed together, which resulted in the uplift of the Ouachita Mountains just north of the site in question.

Geologists believe that the Murfreesboro diamonds are different from the more common diamonds found in kimberlite throughout the world because the Arkansas diamonds formed in the molten lava deep beneath the upper crust, specifically from the carbon dioxide gases in the lava associated with the Prairie Creek volcano.

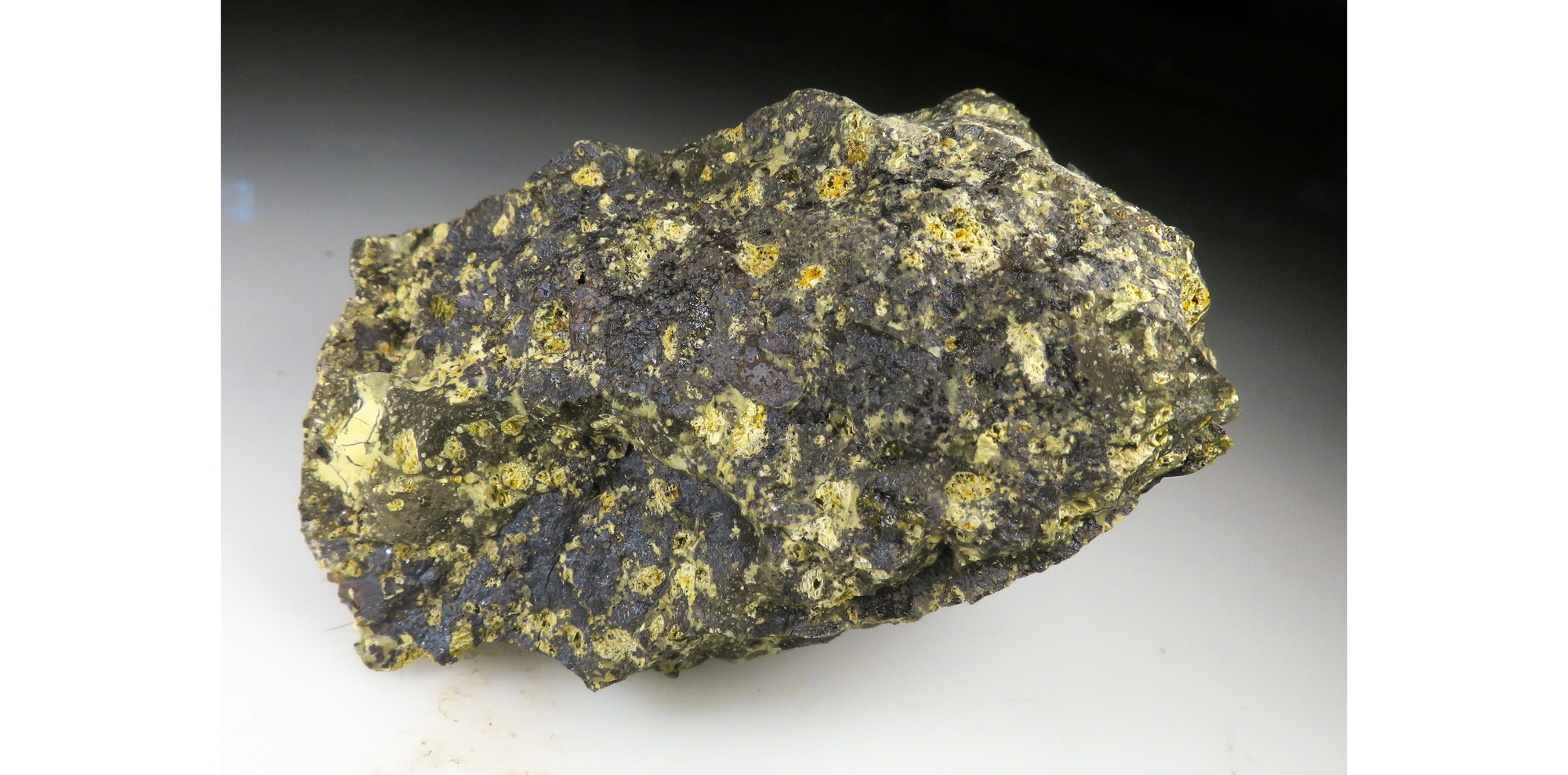

According to this scenario, between 254 and 120 million years ago when the tectonic forces reversed direction and the North and South American plates began pulling apart, creating deep valleys. The chemistry of the lava below was particularly rich in potassium. The steep gap between the two plates allowed the deep magma to rise toward the surface and resulted in the Prairie Creek Volcano erupting. This lava, called lamproite, then rose to the surface into the area today known as the Crater of Diamonds State Park. In contrast, most of the world’s diamonds are mined from kimberlite which lacks the potassium and magnesium chemistry of lamproite lava.

This chemical difference between Crater of Diamond lamproite lava and kimberlite diamond-bearing rocks was stated concisely by one of the State Park’s posters:

Local Geology

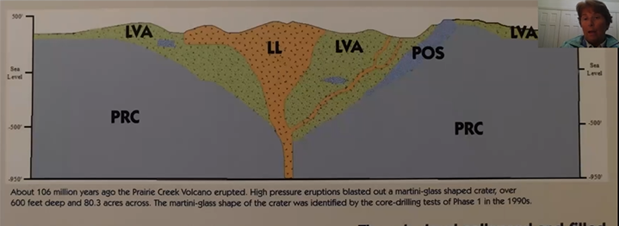

Kathy explained how 106 million years ago, the volcano erupted and blasted out a large portion of the area illustrated below in green and brown colors, in the shape of a martini glass. The volcanic ash cloud then filled in part of the area which was subsequently topped off with emerging lamproite lava. More recent drilling cores throughout the surrounding area helped determine the diamond field to be “80.3 acres across,” as shown below, making it the 8th largest diamond field in the world. The diamonds are treasured by collectors, Kathy said, and they are harder than most diamonds and also hard to find, as she experienced during her Mother’s Day prospecting retreat.

There are a few lamproite diamond fields found in other countries and they share a geochemistry that is rich in potassium, magnesium, and other minerals. Kathy contrasted lamproite and kimberlite with diverse photos.

She added that although there are more than 6,000 kimberlite sites found throughout the world, not all of them are diamond bearing. Additionally, if readers want to see examples of the four different types of lamproite and other interesting information, be sure to visit MSDC's YouTube channel to view Kathy’s presentation in its entirety. There visitors will also see colorful details including photos of some of the largest diamonds ever found at the site.

Famous Arkansas Diamonds

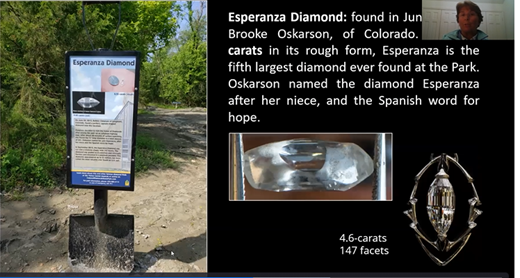

Perhaps to motivate visitors and to encourage them to not give up their search, the Park provides markers throughout the area showing photos of some of the larger diamonds previously found at the exact site where they were discovered. Above is the plaque of the Esperanza Diamond which in its original rough form was 8.52 carats, the 5th largest diamond ever found at the site. After faceting, it resulted in a very clear 4.6-carat jewel.

Kathy stated that “the Uncle Sam Diamond was the largest ever found in history” at the site. In its original form, it was 40.23 carats and was discovered in 1924. Almost a century later, it came to the Smithsonian NMNH and was recently put on display as a 12.42 carat emerald-cut gem.

Kathy recounted the story of how the Uncle Sam Diamond found its way from its discovery, through multiple ownerships and finally as a donation to the Smithsonian.

In June of 2022, the Smithsonian's Department of Mineralogy put on the “Great American Diamond Exhibit” at the NMNH which Kathy encouraged everyone to visit. She noted that the Murfreesboro diamonds are featured in that display. Kathy also showed the following minerals that visitors can also find in the Park:

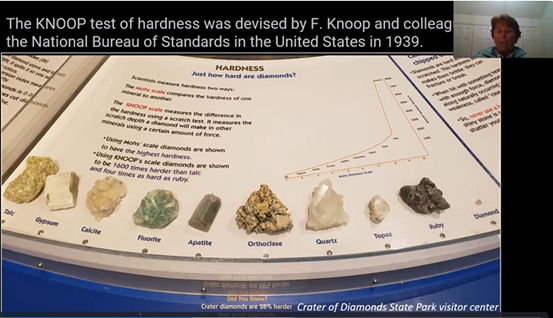

The image below displays the Mohs scale and it shows diamonds listed as the hardest mineral, measured as a 10. But Kathy noted that the diamonds in the Crater of Diamonds State Park are 28% harder than regular diamonds as measured by the Knoop hardness test.

Kathy's Tips for Visiting

Kathy provided a detailed listing of her practical preparations and tools she brought with her to make her trip successful. The following illustration can serve as a guide for future visiting prospectors.

Kathy provided photos of an extensive survey of the area’s diamonds as well as many of her favorites, including these tiny diamonds shown below. She asked, “Why would anyone be interested in these tiny diamonds”? She noted people have found that even the tiny diamonds of Crater of Diamonds State Park command a premium when sold on the open market. As a collector of microminerals, her own interests include searching for mineral inclusions.

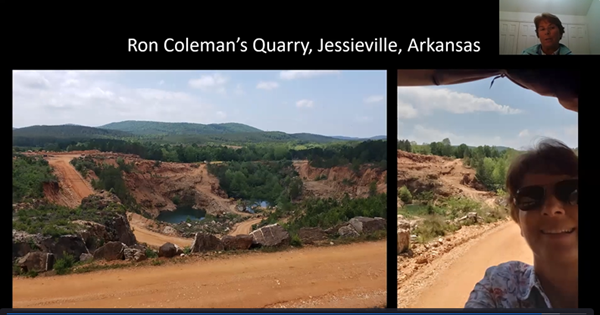

She also provided colorful information about side trips and tours she took between the Little Rock airport and the State Park. As an example, she visited the site from which the NMNH obtained and now exhibits a gigantic slab of quartz. As shown in the two photos below, the hillside cavity background matches that of the photo in the lobby of the NMNH museum where the large quartz slab greets visitors as they walk inside the building.

For more information about how Kathy extended her journey of discovery by purchasing 37 pounds of weathered lamproite potentially containing tiny diamonds. We encourage readers to visit the MSDC YouTube channel and view Kathy’s presentation it its entirety: Diamond Prospecting in Murfreesboro, Arkansas - Kathy Hrechka.

Conclusion

Kenny Reynolds thanked Kathy for her very interesting presentation to which the Zoom audience added their applause. Kathy then fielded numerous questions. Sometimes speakers want the recorded program to stand on its own on our MSDC YouTube channel. So, if you want to be sure to hear future Q&As after our monthly presentation, we’d love to welcome you to our meetings. Check our website and “Upcoming Programs” in this newsletter for specifics.