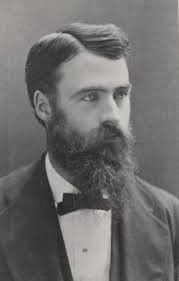

Edwin Eugene Howell, Geologist and Cartographer

by Erich Grundel, Past President of MSDC

Edwin Eugene Howell was an American geologist and cartographer, who produced some of the most detailed raised-relief maps of his time, for which he was regarded by geologist G. K. Gilbert as "a pioneer—if not the pioneer—in the United States."[1] His maps were known internationally, and he produced the first commercial relief map of the Grand Canyon.

If you were a mineral collector in the Washington, DC area in the late 19th or first decade of the 20th century, you probably knew about the Microcosm. If you were involved in any branch of geology and worked at the Smithsonian Institution or the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for sure you knew about the Microcosm. By default you would have also met Edwin Eugene Howell.

Edwin Eugene Howell was born near Rochester, New York on March 12, 1845. Starting in 1864 he began working for Professor Henry Ward’s Cosmos Hall on the campus of the University of Rochester. Working alongside Howell was a graduate of the university who would become one of the most famous American geologists of the 19th Century: Grove Karl Gilbert. The firm specialized in providing schools with scientific specimens, especially biological and geological ones. They also had a natural history museum that attracted many visitors. The company still exists today in Rochester as Ward’s Science.

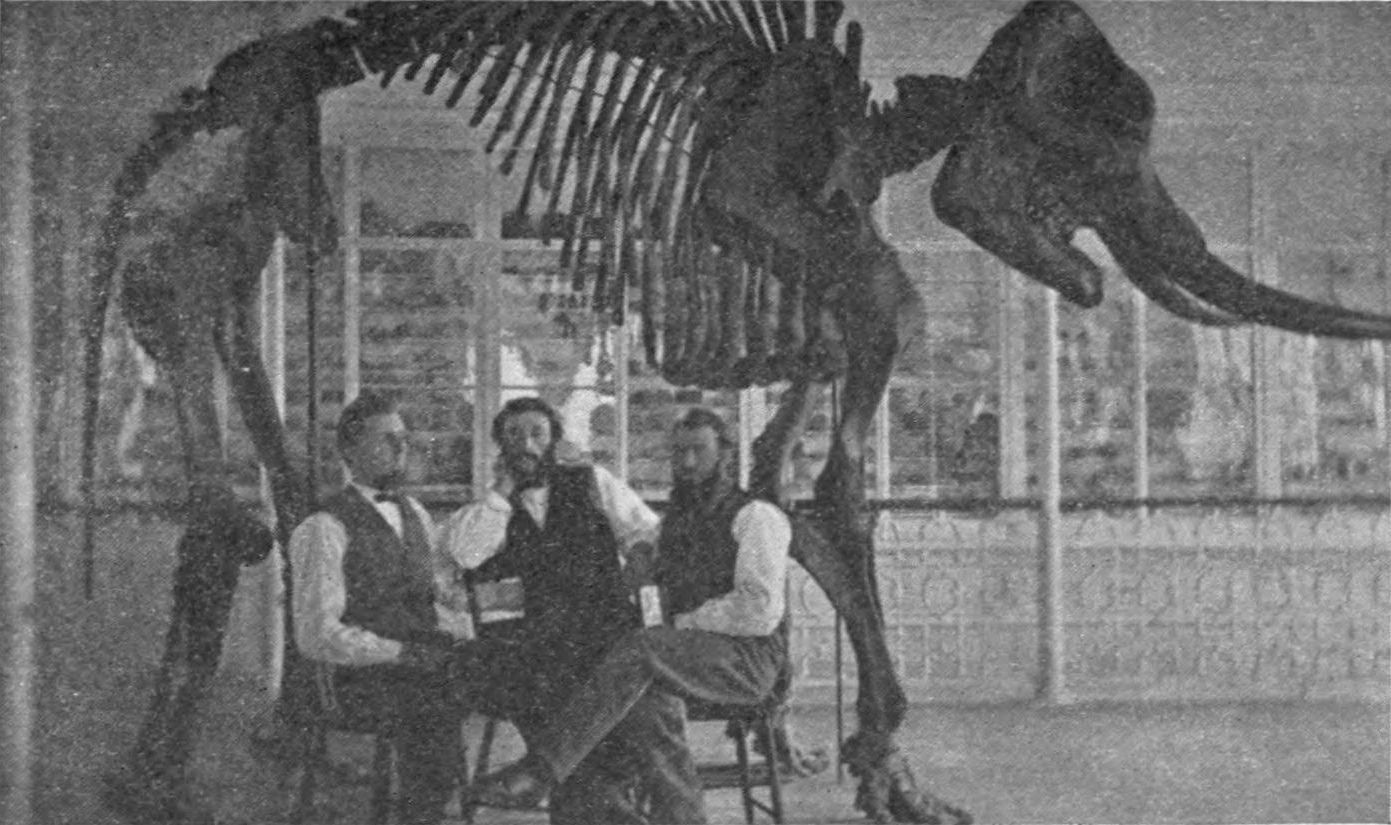

While working for Ward, he and Gilbert helped collect and mount the Cohoes (NY) Mastodon. The skeleton is still on display at the New York State Museum in Albany and has always been the museum’s most popular attraction. In 1872, he joined Gilbert to be part of the famous Wheeler Survey that explored the Great Basin in Nevada and Utah. A few years later he rejoined Gilbert as part of the equally famous Powell Survey which explored the Colorado Plateau in Arizona and New Mexico.

In 1874 Howell and Gilbert relocated to the city of Washington where Gilbert embarked on his long and distinguished career with the USGS. Howell’s only major publication was: Report on the Geology of Portions of Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico which appeared in Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, 1875. Though largely self trained, Howell was regarded as a very competent field worker and geologist.

Back in 1870, while at Cosmos Hall, he created something that would eventually be the thing for which he is still best known. He created a relief map (i.e., 3-D) of San Domingo Island, Haiti. This is thought to be the first such map made in the United States. After completing his work in Washington, he returned to Rochester where he purchased a half interest in Ward’s business and the company was renamed Ward and Howell. He stayed in Rochester until 1892 when he sold his interest in the company and returned to live the remainder of his life in Washington.

In Rochester he created for the USGS a relief map of the Grand Canyon. This map was exhibited at the famous Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876. In 1904 he supplied 56 relief maps for the St. Louis Exposition that marked the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. One of these maps, made of plaster, dealing with anthracite coal mining in Pennsylvania, measured 16’x’9’x6’ and required its own rail car to send it from Washington to St. Louis. An in depth article about Howell and his maps appeared in the September 14, 1904 Washington Post.

Howell and the Smithsonian Institution

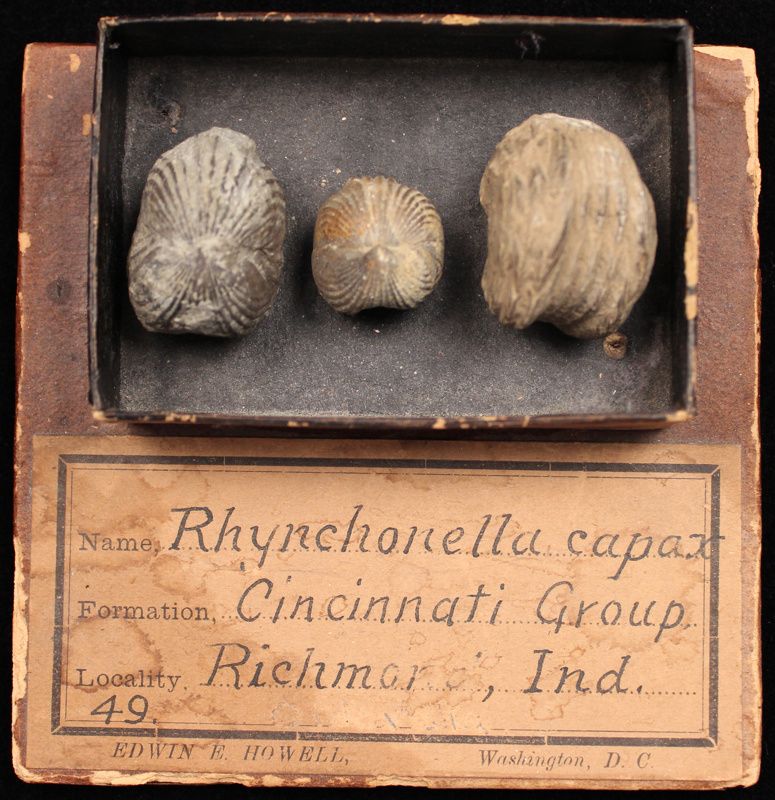

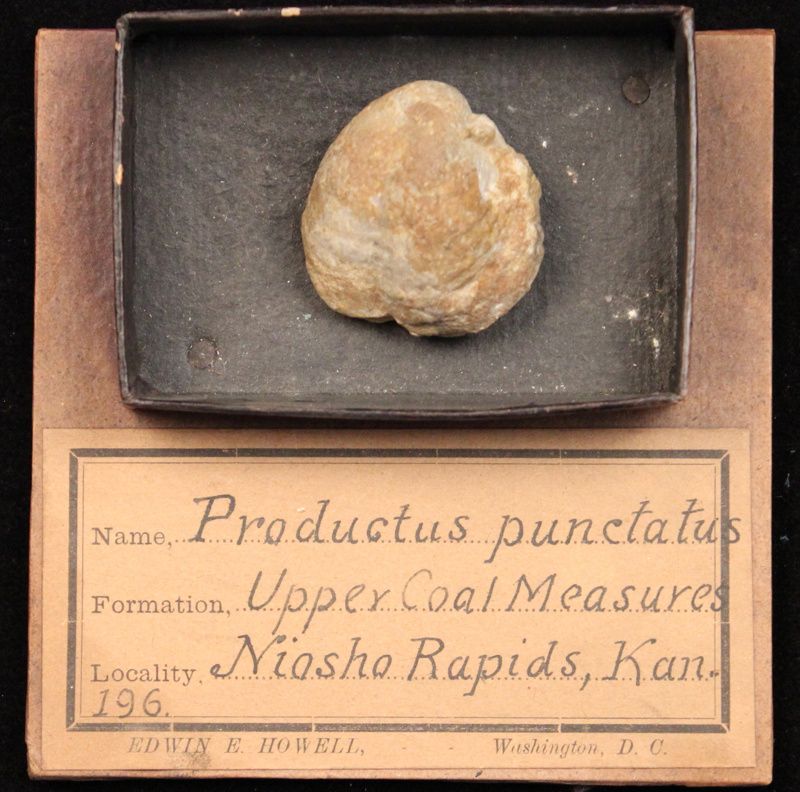

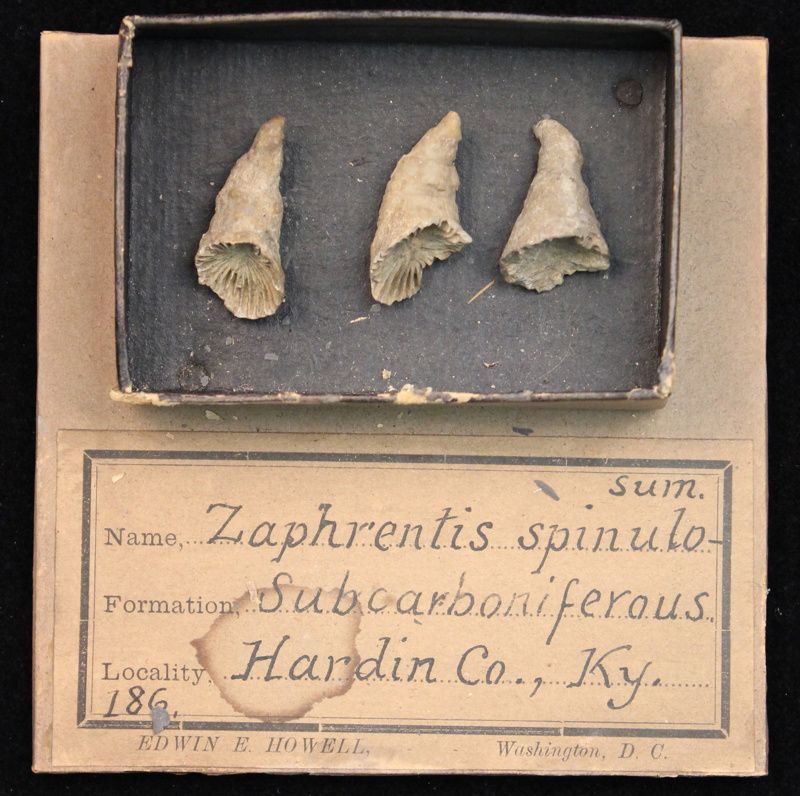

As far back as 1887, staff at the Smithsonian Institution were obtaining specimens from Howell at his various businesses. Accession 18652 (1887) lists Howell (in Rochester) as the provider of some fossils. 21788 (1889, Rochester) is listed as specimens of “siliceous oolite” obtained by Merrill. This is George Perkins Merrill, the person responsible for starting the process of building the SI’s geology and mineralogy collections into the best in the world. Shortly afterwards (21845, 1889, Rochester) Howell traded fossils from New York with Walcott. This is Charles Doolittle Walcott the future Secretary of the SI and the discoverer of the Burgess Shale in Canada.

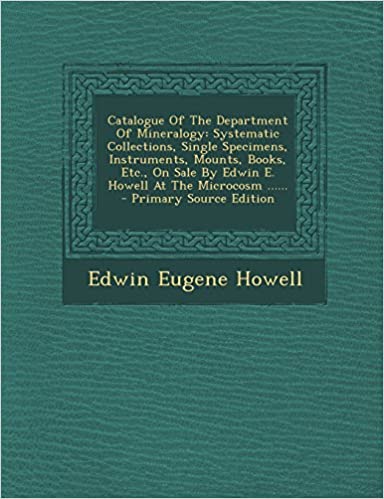

In 1892, Howell relocated to Washington to open the Microcosm at 612 17th St. NW. This site is today office buildings located across the street from the Old Executive Office Building (during Howell’s time the War Department) on the grounds of the White House. The Microcosm, a name derived from Ward’s company, was a magazine and a business devoted mainly to making relief maps, selling geological educational and collector type specimens and tools. He issued a number of catalogues a few of which are still extant.

Due to the store’s proximity to the Smithsonian, his dealings now accelerated and were continuous for nearly two decades. Item 25262 (1892, City (i.e., Washington) is for the sale of “9 specs. of minerals” on December 20. The purchaser was Yeates. William Smith Yeates was the former State Geologist of Georgia and then Assistant Curator of Minerals at the Smithsonian. Merrill and Yeates made frequent visits to see Howell at his Washington store. Another notable person also doing much business with Howell was Frank Wigglesworth Clarke, Chief Chemist of the USGS, who from 1883 until his retirement served as Honorary Curator of Minerals. Item 26529 (1892, City) was an exchange of 14 specimens between them.

In 1893 Yeates obtained specimens (26713, 26828) of “pink tourmaline in lepidolite from San Diego Co., Cal.”. Specimens such as these may still be seen at mineral shows. In 1897 Merrill purchased a gold in quartz specimen (31672) from near Chancellorsville, VA for display at the Nashville Exposition. A unique purchase in 1894 was that of a python (28011) for the purpose of obtaining its skeleton. The purchaser’s name is indistinct.

Of special note are the purchases of meteorites (28925), including two from Japan that Clarke acquired from Howell to be put on display at the Atlanta Exposition in 1895. Collecting and studying meteorites was by no means common back then and it was these early purchases that led to the Smithsonian’s collection of these objects becoming the best anywhere. More than anyone, it was Merrill who was most active in obtaining these other world visitors.

One of the last transactions made was on February 11, 1910 when “Trans. 500 lbs. rocks & ores” changed hands. It is not clear from the entry (File S.S 32/14) who got all of this material. Perhaps the Smithsonian was disposing some of its leaverite (as in "leave 'er right where you found it") specimens.

In total, more than 70 transactions are recorded as having taken place between Howell and the Smithsonian staff. It is not known if any of the Howell items are currently on display. Some years ago I was unsuccessful at persuading a staff member to provide pictures of some of the accessions. If some of these specimens were thought worthy for display in the 19th century, why not see them in the 21st? I've subsequently learned that several photos of Howell's specimens can be found on the internet and are shown here.

Howell and the Washington School Collections

As noted, the Microcosm also dealt in educational material, including mineral sets, some referred to as the Washington School Collections. One of his first catalogues: Catalogue of the Department of Mineralogy begins with an endorsement from John Wesley Powell, Howell’s former boss and the famous explorer of the Grand Canyon, former Director of the USGS, and at that time an anthropologist at the Smithsonian. There are other endorsements. Here are a few:

“Mr. Howell has also supplied collections of minerals and rocks to each school in the District of Columbia. These have also been found valuable, much work having been done by means of them in identifying minerals and rocks, thus training the perception of the children to know these objects in nature when they see them. These collections are so well arranged as to be workable by the ordinary intelligent teacher.”

W.B. Powell, Superintendent of Schools, Washington, D.C., November 9, 1894

No doubt the comment about teachers was written before the advent of the National Education Association. Unfortunately, in today’s heavily urbanized environment, children in DC have restricted contact with nature, especially minerals. In the recent past a few individuals have reached out to the DC Public Schools and provided study specimens of minerals to try and spark the students’ interest in the subject. Perhaps it is time to try again?

On December 7, 1894 Joseph LeConte, the famous professor of geology at the University of California, Berkeley wrote:

“We entirely agree in thinking the collection judiciously selected and, considering the price, very excellent.”

Unfortunately, endorsements from LeConte are not in favor anymore due to some of his social and political views.

One more:

“Enclosed find $8.00 for two sets of Washington School Collections Nos. 2 and 3, including one duplicate set of fragments of each. These collections are the best for the money that I have ever seen.”

Owen W. Mills, Principal, Bramanville Grammar School, Millbury, Mass., November 7, 1894

Getting more bang for the buck never goes out of style. The following seems to support Mr. Mills (Why shouldn’t he feel this way. He seems to have underpaid as the following price information indicates).

Collection No. 2 contained 40 minerals labeled in a case (“2½x1¾ inch tray/specimen”) with a descriptive text, price $2. Duplicate fragments 25 cents/set. Collection No. 3 is like No. 2 only it has 40 rocks and the pricing is the same. Collection No. 1 had 20 minerals and 20 rocks pricing is the same as 2 and 3. There was a collection No. 4 which contained 24 fossils. Howell also had other collections that contained as many as 330 specimens and could cost as much as $250. He also sold rock trimmers that look much like ones available today, hammers, magnifying glasses etc.

Micromounts

Especially interesting he sold “slides for the microscope of crown glass, rounded edges” of minerals. These are micromounts! As a form of mineral collecting, micromounting only got started in the 1870s. He lists 9 different minerals “and others” available for 50 cents /slide. Mounting minerals on glass slides was giving way to the paper box pioneered by Rev. George Gilbert Rakestraw of Philadelphia.

Ads for micromounts in the 19th century are uncommon. The only other dealer in the United States selling them, to the best of my knowledge, was Geo. L. English & Co. (NYC) who sold both glass and boxed specimens. To see micromounts for sale in Washington in the 1890s is remarkable. There are no entries indicating the Smithsonian purchased any from Howell. Did the USGS purchase any? Finding such treasures would be an amazing discovery. Glass artifacts seldom survive intact.

Today, anything bearing Howell’s name is a collector’s item. One last note about Howell. In 1893 he joined a like-minded group, including the other men mentioned here, and founded the Geological Society of Washington. He died in Washington on April 16, 1911.

The following provided information used in this article:

· Archives of the District of Columbia

· Archives of the Smithsonian Institution (DC)

· Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester (NY)

· Historical Society of the District of Columbia

· Library of Congress (DC)

· United States Geological Survey Library (Reston, Virginia)

· Robertson, Eugene C. (Ed.), Centennial History of the Geological Society of Washington, 1993.