Guano: The White Gold of the Seabirds

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

Imagine a natural resource that, after discovery, is found to be so efficient and powerful that it revolutionizes an entire industry. Deposit-holding countries, businessmen, and speculators get rich. Laborers remove it from the ground, and ships carry it around the world, where it helps to power everyday life. Thanks to the social habits of the birds that produce it, it tends to be available in huge, concentrated, perpetually regenerating heaps.

For the second half of the 19th century, much of the Western world relied on such a resource, a super-powerful substance called guano, or bird poop. Made almost entirely of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium, it served as an amazing fertilizer that provided straight-up energy for plants.

When its powers became known, demand quickly outstripped supply and world powers fought for the remaining supplies. Unprecedented legislation was passed, questionable diplomatic decisions were made, and power struggles among countries ensued.

Before Europeans “discovered” guano, the Inca took advantage of these properties for hundreds of years. Inca kings were well aware of the benefits guano would have on crops and imposed strict rules for mining that basically took the resource out of the hands of private sector "guano lords," and ensured a sustainable harvest.

The Beginning of the Guano Boom

For centuries, European explorers and colonizers, blinded by shinier commodities, did not bother to look into guano. The first to do so was the Prussian naturalist, geographer, and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, who could not ignore it. Humboldt had traveled to Peru for research and noticed the constant shipments of the ammonia-rich guano which made him sneeze. When Humboldt returned to Europe in 1804, he brought back some samples and turned them over to “the best analytical chemists of the day."

The chemists immediately recognized that they were dealing with powerful stuff. Farmers in Europe and in the U.S. were beginning to worry about their depleted soil’s ability to feed a growing population. Although many different types of fertilizers were tried, none were as chemically promising as guano, which is full not only of nitrogen, but also is packed with phosphate and potassium.

The Guano Trade

Thus began the guano trade – on three tiny Peruvian islands in the Pacific – and their product ultimately reached farmers’ fields around the world.

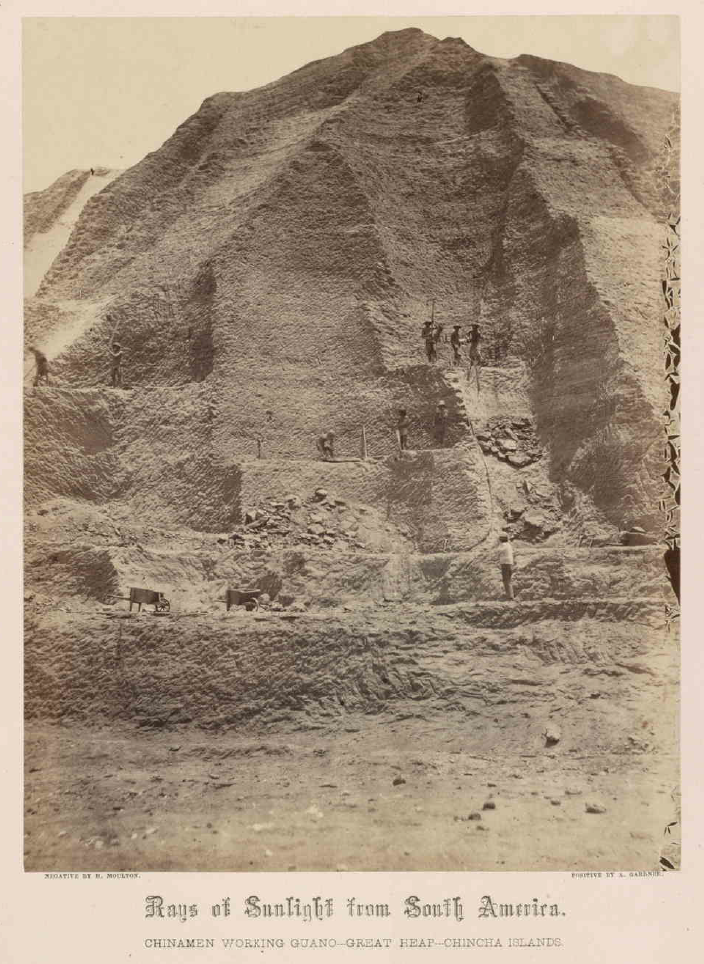

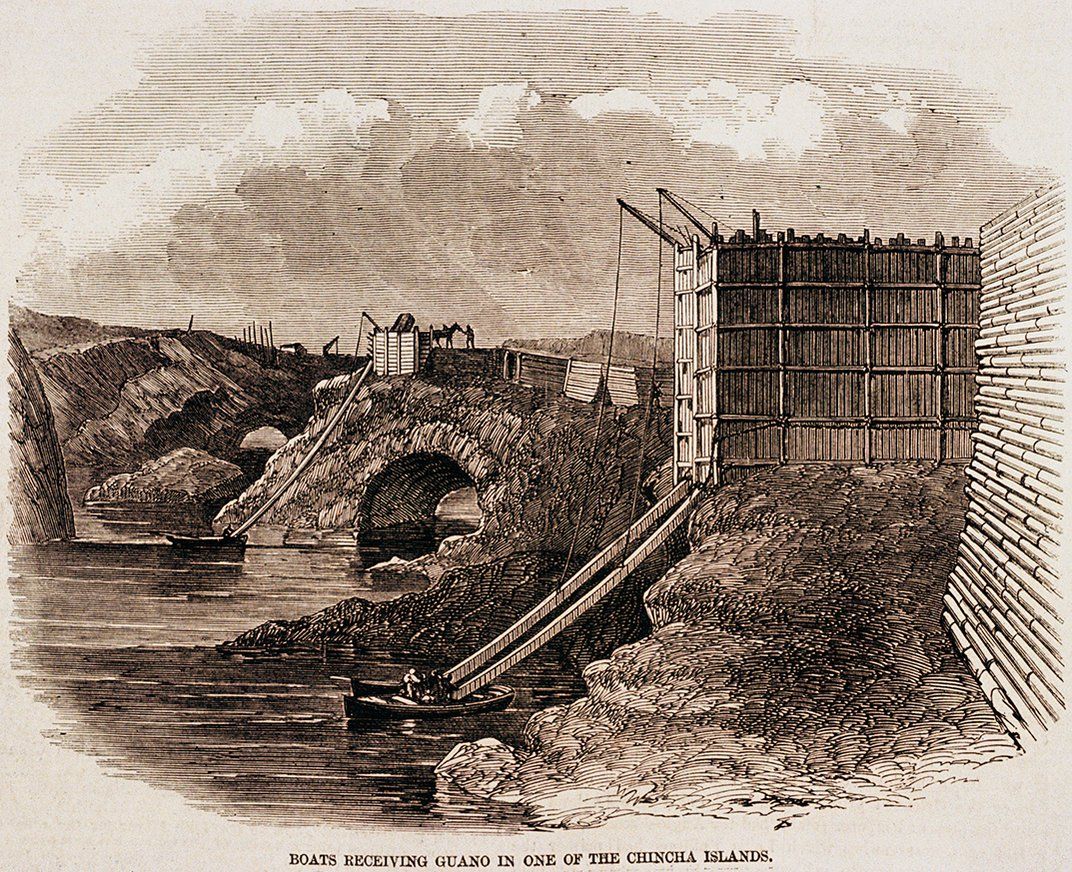

The three tiny Chincha Islands lie off the southern coast of Peru. For millennia, they served as home for seabirds. The birds fed and bred in the rich waters packed with fish and absent of predators, allowing their droppings to accumulate to a depth of up to 200 feet. The dry weather and cool ocean currents there maintained the guano’s nitrate-rich quality.

In the early 19th century, farmers and chemists worldwide claimed that Chincha Islands guano was the world’s finest fertilizer. Hundreds of British, German, and American ships purchased it from the Peruvian government for their own agriculture, waiting offshore up to eight months to load the precious cargo.

These nations’ ships also sought, claimed, and mined other guano islands in the Pacific and Caribbean. Although they recognized the practices weren’t sustainable, they continued to harvest the guano. By the late 1870s, nearly all of the Chincha Islands guano was gone, and the seabird habitat was ruined by the mining operations.

In the heyday of the guano trade, up to 300 ships per year visited the Chincha Islands and waited offshore to load. When the loading started, all inside doors and windows were closed and tightly covered with canvas to prevent the toxic dust from filling a ship’s crew spaces. Loading crews were limited to 20-minute shifts in the cargo holds and the rest of the crew climbed to the tops of the masts to breathe fresh air.

The Guano Islands Act of 1856

By the 1840s, the remarkable properties of Peruvian seabird guano were widely recognized, as farmers claimed that using the fertilizer increased their crop yields up to three times. American farmers demanded the nitrate-rich fertilizer from Congress to restore their worn-out fields’ soil balance and increase production.

In his 1850 State of the Union address, President Millard Fillmore said that guano from Peru was so valuable that the U.S. government should "employ all the means properly in its power" to get it.

The resulting Guano Islands Act stated that the U.S. could claim any island that had seabird guano on it, so long as there were no other claims or inhabitants. Any guano mined had to be sold to American farmers as fertilizer at a reasonable price. Guano was at the time the finest natural fertilizer and farmers needed it to replenish the nutrients in their fields and increase their crop yield. This act authorized our nation’s earliest significant annexations of lands beyond the continent.

Around 200 guano islands were claimed by Americans in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Nine remain today as unincorporated territories. Some of them are pretty well known: Howland Island, where Amelia Earhart was supposed to land; Midway Atoll, a strategic key to America's defeat of Japan in World War II, and Johnston Atoll, a little speck of coral in the Pacific so remote that the U.S. tested nuclear and chemical weapons there before abandoning it a few years ago.

Sources include:

1) The Guano Trade, Smithsonian National Museum of American History

2) The Smithsonian and the 19th century guano trade: This poop is crap, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, by Paul F. Johnston, May 31, 2017

3) Wikipedia, Alexander von Humboldt