North Carolina’s Link to the Washington Monument

Text adapted from “The Secret’s at the Peak of the Structure” by Kempton H. Roll, Rock & Gem Magazine, February 1997

By: Ken Rock, MSDC Newsletter Editor

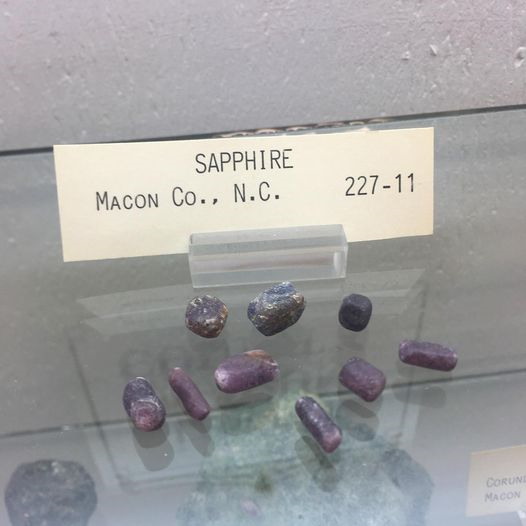

What does the Washington Monument have to do with the gems of North Carolina? Answer: more than most people realize. Attached to its top is a five-pound pyramid of solid aluminum. The aluminum was made from rubies and sapphires mined primarily in North Carolina.

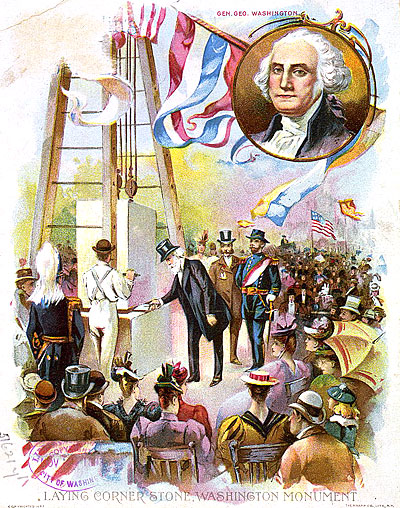

When the monument was finally topped off in 1885, the event was reported widely because the government decided to do it with a specially created cap at the apex: a pyramidion, as they called it, made from aluminum. The ceremony marked the culmination of 37 years of hard work (see image of cornerstone laying at left) – with time out for the Civil War – so the whole nation was excited about the event. Perhaps most excited were the metallurgists of that period because it marked the first time that the unique properties of the newly discovered metal, aluminum, were brought to the public’s attention.

What better way to crown the top of America’s monument to one of its greatest presidents? This “new” metal was much lighter than steel yet surprisingly strong, had excellent corrosion resistance, and was a good conductor of electricity. It was as precious as silver (silver and aluminum cost the same in the late 1800s), could be cast into the shape of a pyramid, polished to a high luster, engraved for posterity, and allow the United States to demonstrate its leadership in material science and industrial technology. The only problem was that aluminum at the time was very difficult to produce and, therefore, very expensive. It was definitely not the familiar household metal it is today. As it turns out, the best source of aluminum was the corundum crystals being mined commercially in the gravels and mountainsides mostly in Clay and Macon counties in southwestern North Carolina. Crystals of corundum are more familiar to us as sapphires and rubies. They are the gemstones that rockhounds have been seeking at Carolina gem mines for years.

To turn the mineral corundum, aluminum oxide, into metallic aluminum was far from an easy process. After the mineral crystals were crushed into fine particles, they had to be converted chemically into aluminum chloride and then reduced with metallic sodium to form salt and metallic aluminum. Known as the Sodium Reduction Process, it was the main reason why aluminum production was so costly. The primary reducing agent, metallic sodium, was in itself expensive, but because it also was extremely reactive (bursting into flame on exposure to air), the process was very difficult, dangerous, and costly.

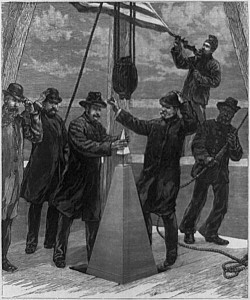

After the masonry work on the monument was completed, the final topping off was scheduled for December 7, 1885. However, Tiffany & Company had other plans and achieved a marketing coup to delay that event. Perhaps because of its link with the source of the crushed gem ore, the jeweler succeeded in “borrowing” the polished aluminum pyramid from display in its Fifth Avenue store.

With appropriate promotional flair, Tiffany & Company then invited its customers to come in and see this precious, soon to be famous, piece of metal and, if they were so inclined to “step over the top of the Washington Monument.” All the customer had to do was be willing to stand in line of Fifth Avenue to await his or her turn to climb the small stair on the showroom floor.

It is likely that many New Yorkers would later in life boast of their physical prowess to envious friends and relatives. It actually was quite a distinction – the pyramid would crown what was then the world’s tallest manmade structure!

Historical Note

For a number of years, almost all of the corundum used in the United States and much of Europe came from mines in the Carolinas. Prior to the first World War, Germany was the largest consumer. The Corundum Hill Mine produced some very large crystals, most (but not all) of which were crushed to bits. The mine and others in the area became not only important producers of corundum for abrasives and jewel bearings but were considered by the metallurgists of the day to be the best, if not the only, source of high-purity aluminum oxide.

Today, bauxite is now the preferred ore for aluminum with production costs a fraction of producing aluminum via crushed corundum. Bauxite is a hydrated aluminum oxide ore typically found in the topsoil of various tropical and subtropical regions. Using bauxite to produce aluminum oxide resulted in costs plummeting by 80 percent almost overnight.