The Famous Silver Mines of Kongsberg, Norway

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

Author's note: The photos of mineral specimens in this article are taken from the Internet, mostly from the websites of mineral dealers. I’ve included the very colorful and highly detailed descriptions of the minerals as provided on the website.

Legend has it that in the summer of 1623, two children were tending their cattle in rural Norway when the ox they had with them scraped the side of a mountain, revealing something shining and glimmering. They took some of these rocks home and showed them to their parents. One of the fathers recognized these rocks as silver, smelted them, and tried to sell the metal in nearby villages. Because of the low price being offered, the local authorities suspected that the farmer was selling stolen silver and arrested him. The farmer was given the choice of telling where he had found the silver or being sentenced to hard labor. To secure his release, he revealed where the ore had been discovered. This discovery led to the establishment of the Silver Works at Kongsberg, located approximately 40 miles west southwest of Oslo.

Mining History

The Kongsberg silver mines were founded by and named after King Christian IV of Denmark and Norway in 1624. The king pronounced, “through the merciful blessing of almighty God, the silver belongs to the Crown.” The king invited German engineers and other specialists to develop the silver mines and help build the mining company. As a mining city, Kongsberg had a distinct urban culture that contrasted with its surroundings, strongly influenced by the traditions of mining communities in Germany and where the German language was extensively used in mining business and for religious services.

In the early years, nearly half of the city's population were German immigrants. Well into the 19th century, the majority of the engineers and executives were German immigrants and their descendants became a distinct social class called mining families that formed the educated social elite of Kongsberg. By the 18th century, Kongsberg was Norway's second largest city, second only to Bergen.

The German miners brought with them the ability to work hard rock with two techniques, "hammering" and "firesetting," which were most often used in tandem. However, as the mines extended downward, it was soon recognized that the rocks were harder and tougher than the German miners were used to. In the 1650s, a crisis was reached when management received notice that some workers had made a monthly advance in their tunnels of less than 8 inches. Records indicate the 1660s were a transition period from "hammering supplemented by firesetting" to "firesetting supplemented by hammering."

Early Mining Techniques

The first recorded evidence of the firesetting technique being used at Kongsberg was an account of an unhappy miner being burned while setting a fire in the year 1624. Firesetting involved placing and then igniting carefully stacked sticks of wood at the tunnel face. Fire would heat the rock wall causing cracks to develop and chips to flake away. Miners learned that a continuously burning fire maintained a very hot wall face and was the most efficient technique for mining. Though often referred to in literature, the so-called process of "quenching the hot rocks with cold water" was not used at Kongsberg (and probably very few, if any, other places) because to do so would be inefficient, dirty, and most certainly dangerous.

The hammering technique required as its main tools a sharp-pointed chisel with attached handle and a hammer. At Kongsberg, miners usually hammered long, parallel, vertical chisel marks in the mid-section of the tunnel face, in an area going from roof to floor. When this area was hammered out to a certain depth, the side rocks were removed by firesetting until a proper tunnel width was achieved. Besides hammers and chisels, they also used wedges and sledges on fractured rocks.

The first use of black powder for blasting occurred in 1659, but it wasn’t until the mid-1700s that blasting was commonly used. Firesetting, however, continued to be used to create horizontal works because of its low cost.

Working and Social Conditions

Firesetting caused miners to work in filthy and choking conditions. It consumed oxygen and produced smoke, ashes and carbon monoxide/dioxide, called "stench" by the miners. Mining in areas with inadequate ventilation quite often resulted in fatalities. This is illustrated by an inscription called "the death notice," hewn into a rock wall of the underground adits located between two mines. The notice commemorates two miners who, in 1794, were killed in the mine by "stench."

The problem of ventilation was aided by the use of an “adit loft,” which was created by dividing the adit by wood or brick into a lower level where the miners worked and an upper level for the smoke. Ordinarily, natural ventilation from the surface ceased at any more than 200 meters from the shaft. It is estimated that the long distance of some adits, and the bad air within, hindered their completion for decades.

A detailed employment report for the year 1732 listed the ages of the 1,619 employees working for the Kongsberg mines. The list included five boys under age 10, and 272 aged between 10-14. While boys were not permitted to work underground, some were assigned hard and often dangerous work in the surface ore crushers and sorting houses. At 18, young men could apply for work underground.

A miner's daily life was far from easy. Ringing church bells signaled the beginning of a new day at 4:00 am, when miners began the long walk up the mountain to the mine shaft. There, they had to attend prayers before entering the nearest mines. Late arrivals for the prayers were fined. Using tallow lamps or pine torches for light, miners climbed down wooden ladders 650-1,300 feet to their working levels. It was then that the work day began.

At day's end, sweat-soaked miners retraced their steps and trudged down the mountain, frequently in rain or snow. In town they usually attended more prayers and devotional services in the church. Those who were caught sleeping in the pews were hit over the head with a long pole by an overseer. One habitual sleeper was fined 4.5 dalers, almost one month's salary.

After the use of dynamite was introduced in 1872, firesetting was abandoned, its last recorded use in 1890. The mines were initially dewatered using hand pumps, but waterwheels were soon installed to operate pumps. Many canals and aqueducts that were used to bring water to power the wheels can still be seen today. Steam power and electricity were introduced to the mines in the 1880s.

An Impressive Legacy

For 335 years (from 1623 until 1958) the Kongsberg silver mines were an important part of Norway’s economy and industrial development. The high point of mining in the district occurred in 1770, when 78 mines employed about 4,000 workers making it the largest pre-industrial working place in Norway, supplying over 10 percent of the gross national product of the Danish-Norwegian union. The particularly rich King's mine operated to a depth of ~3,300 feet. By 1805, however, much of the best ore had been extracted and most of the mines closed, although significant new ore discoveries were made, especially in the 1830s and 1860s.

During their last 30 years of operation, the mines lost money. After extensive prospecting failed to locate new orebodies, the Norwegian government decided to close the silver mines and the last silver smelting took place in 1958. Total production exceeded 1,400 tons of silver after operating for 334 years.

Finally, on to the Geology

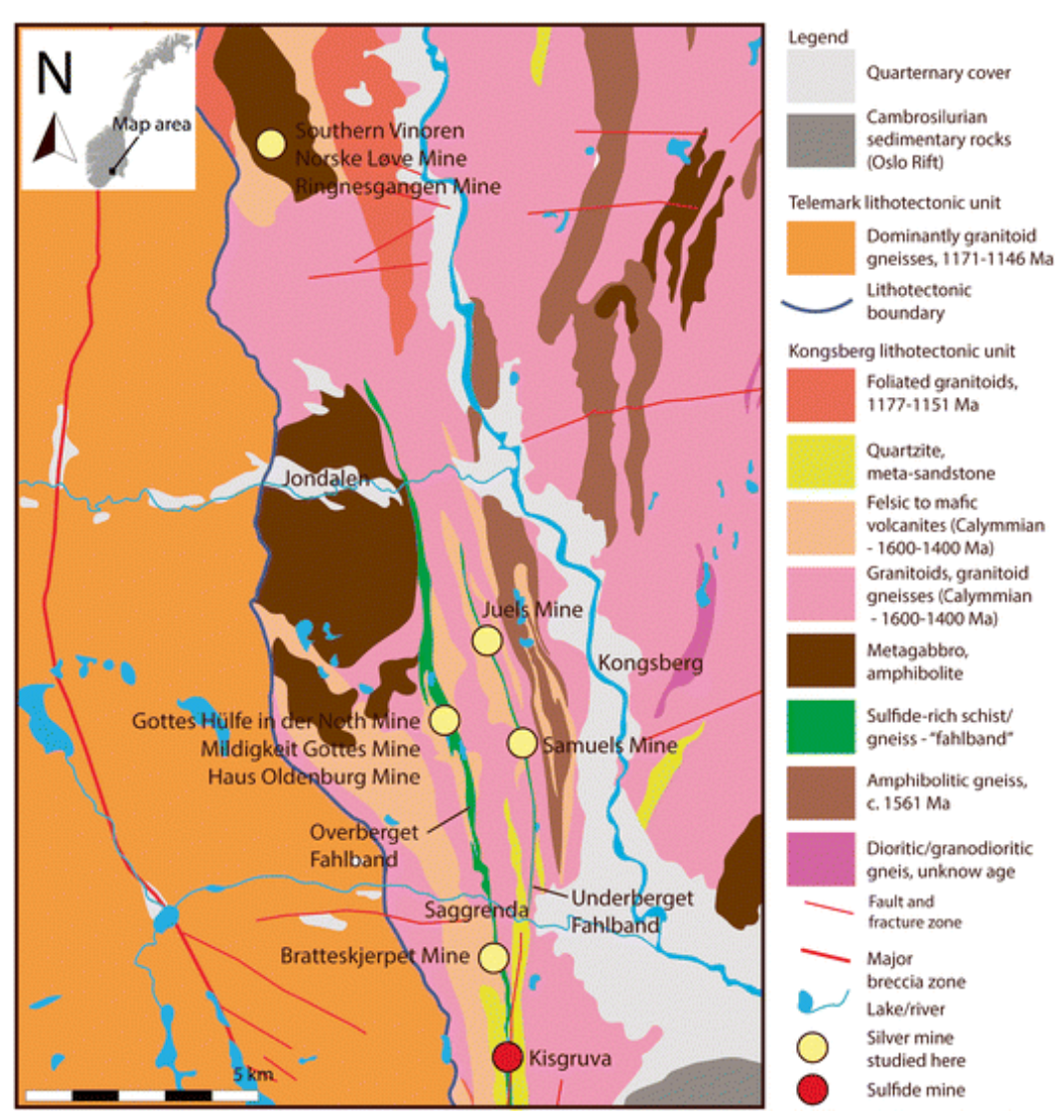

The area of ore bearing rock is about 9 miles wide trending along a north-south line for about 18 miles. Forest cover of Norway spruce and Scots pine dominates the landscape with ground vegetation that includes heather, bilberry, lingonberry, mosses, and lichens.

The oldest rocks in the Kongsberg area began as volcanics that were intruded by gabbros and diorites followed shortly by the first event of deformation metamorphism. Ultimately, these events created bedrock consisting of quartz-plagioclase-biotite gneiss, mica and chlorite schist, amphibolite, and granite gneiss.

The ore deposits at Kongsberg are a found in a vein system that includes cobalt, nickel, arsenic, silver, and bismuth. The hydrothermal system that formed the veins has been dated at 265 million years old. The silver in the deposits is derived from the black shales of the Oslo region which have been calculated to contain more than enough silver to account for the Kongsberg deposits. Minerals found in the hydrothermal veins include quartz, pyrite, calcite, baryte, fluorite, galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite, silver sulfosalts (minerals that contain arsenic and antimony in place of some metal atoms), argentite, native silver, and pyrrhotite.

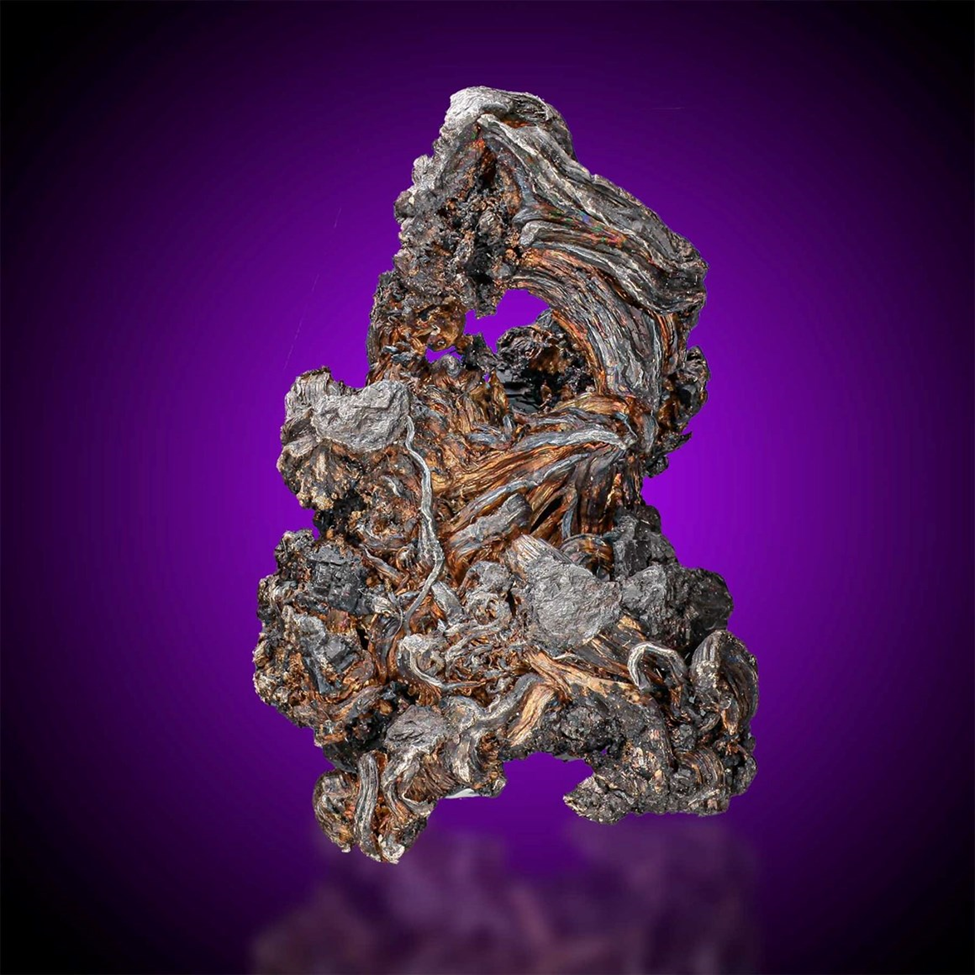

The Kongsberg deposit is characterized by native silver-calcite-nickel-cobalt-arsenide veins. The grades of these veins generally ranged from 100 to 350 grams per ton of silver, with some ore shoots contained twice this amount and lumps of native silver weighing over 1,000 pounds were sometimes found.

Kongsberg Mineral Specimens

The Kongsberg Mines in Norway are renowned for their exceptional silver mineral specimens. These specimens are highly sought after by collectors for their unique visual characteristics, including a metallic luster, twisted wires and crystals, intricate growth patterns, and diverse textures. The mines also produced a variety of silver-bearing minerals, such as argentite, proustite, and pyrargyrite. These minerals often showcase beautiful color variations.

Kongsberg silver specimens have for centuries been among the most highly desired of all collectible minerals. Significant specimens of Kongsberg silver grace the majority of the world's major natural history museums and the top specimens in private hands are highly sought after by collectors worldwide.

According to Jean-Claude Boulliard, Curator at the Sorbonne, Paris, France, in his book "Mineraux remarquables," Kongsberg silvers "remain unparalleled to this day." He further shares that, "In the eighteenth century, many of the most beautiful specimens of native silver were given by King Christian VII (King of Denmark and Norway from 1766 to 1808) to other European monarchs."

It is not uncommon to see Kongsberg silver specimens for sale at the Tucson Gem & Mineral Show and other major shows that have a series of old labels documenting their provenance and showing a remarkable upward trend of prices. I’ve seen as many as six different labels, some very old, for some exceptional pieces. Dealers say that there is consistent demand for quality specimens from Kongsberg and from my discussions, are not especially keen on discounting their prices to make a sale.

Note for collectors: The Kongsberg silver mines are now protected as historical sites. Collecting inside the mines and outside on the dumps is illegal.

Open for Visitors

The mining museum in Kongsberg is currently the city's main tourist attraction with the museum and its staff serving as the greatest single source of information about the Kongsberg district. The museum's three-story building originally housed the mines' smelter and coin mint. Today it is filled with exhibits of old mining machinery, smelter furnaces, tools, lamps, maps, photographs, minerals and gemstones, and much more. These exhibits present an impressive story of Kongsberg mining history.

Since its closure in 1957, the silver mine has been preserved. Some 40,000 visit the museum annually. The tour includes the first man engine (automated ladder) in Kongsberg in action. The museum also gives visitors an opportunity to board the "mining train" which brings you 1.4 miles into the King’s Mine, the largest of the silver mines.

You can enjoy a virtual experience of going into the mine via drone by clicking here.

Kongsberg remains the site of the Royal Norwegian Mint which mints Norwegian coins. The city also produces circulating and collectors' coins for other countries. Kongsberg is also the home of Norway's major defense company, Kongsberg Gruppen, that was founded in 1814.

Sources

Mindat.com, Nathalie Brandes,

New Mexico Bureau of Geology & Mineral Resources, New Mexico Mineral Symposium — Abstracts, The Famous Silver Mines of Kongsberg, Norway, 36th Annual New Mexico Mineral Symposium, November 13-15, 2015, Socorro, NM. Natalie N Brandes and Paul T Brandes.

PorterGeo, Kongsberg - Kongens Gruve, Norway.

The Free Library by Farlex. Kongsberg Revisited.

The Mineralogical Record (Vol. 32, Issue 3), May 2001, Peter Bancroft, Fred Steiner Nordrum, and Peter Lyckberg,

Wikipedia, Kongsberg Silver Mines.

YouTube: Bli med på en flytur i sølvgruvene i Kongsberg.