November Program Report: Into the Andes - - Quiruvilca, Peru; Presented by Ray McDougall

Synopsis by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

Our speaker for November, Ray McDougall, provided an overview of the extraordinary minerals of Quiruvilca. It was based on his 2013 trip to Peru with his long-time collecting friend David Joyce. The slides in this presentation were prepared by both Ray and David.

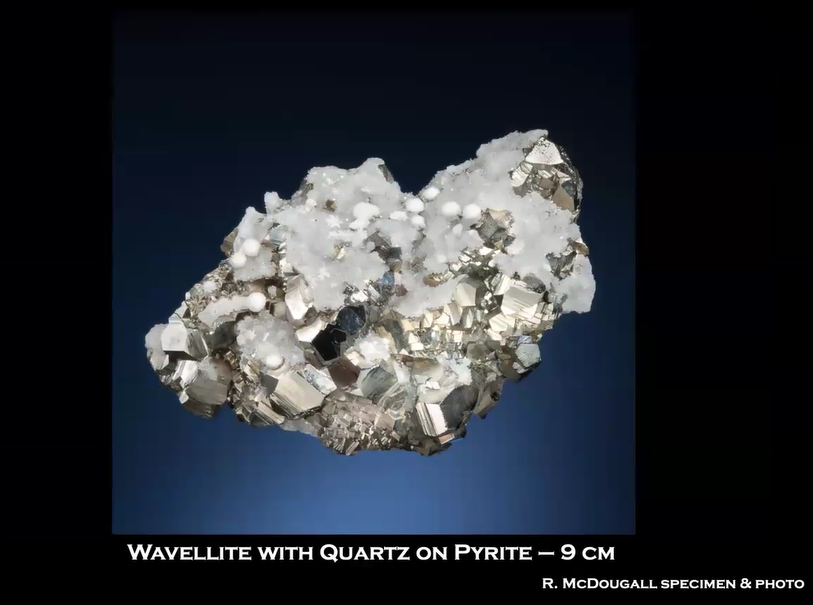

Since the late 1700s, Quiruvilca has been known as a source for multiple metals – primarily copper, lead and zinc, along with some silver and gold. Over the most recent decades, the area has gained additional fame as a source for extraordinary mineral specimens, particularly pyrite, orpiment, enargite, bournonite, and hutchinsonite.

Ray began his presentation by sharing the back-story of how this trip came about. In Ray’s prior career as a corporate-securities lawyer, he helped his client to negotiate the acquisition of the Quiruvilca Mine. When the deal was complete 15 months later, the grateful owner invited Ray to visit the Quiruvilca mine as his special guest. This was a mineral collector’s dream.

Readers: The purpose of this report is to encourage you to go to the video of Ray’s presentation so you can experience it in his own words. You can find it here.

Additionally, you can read Ray’s own published description of his adventure written shortly after his return home to Canada. Click on the following link to his website to see that article which contained 10 photos of Quiruvilca minerals: Into the Andes: Quiruvilca, Peru | McDougall Minerals. Ray's presentation to MSDC included additional photos of extraordinary Quiruvilca mineral specimens, added over the years since the original article was written.

The synopsis below is written by MSDC’s secretary. The original article, and of course the video of Ray’s 2024 presentation, contain additional informative geological slides and explanations beyond the following pages.

Beside this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see minerals up close in their natural habitat, just getting to this Peruvian mine site made Ray’s trip particularly exciting. After a flight to Trujillo, Peru, the drive into the Andes mountains was not for the faint of heart. The photo below barely shows the road in the middle left of the slide, clinging to the mountainside above the Moche River valley.

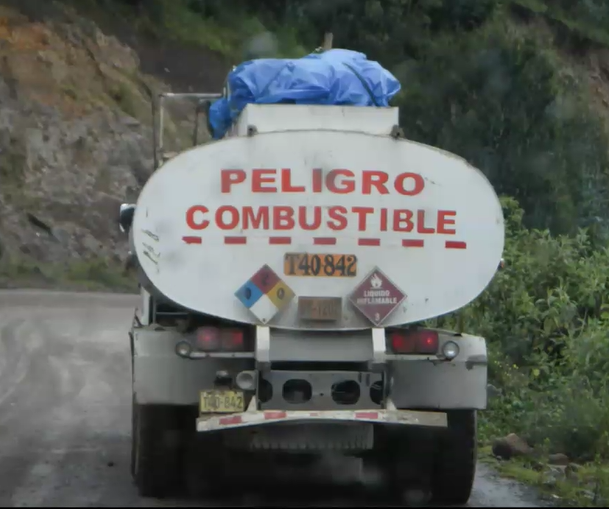

The hazardous roads were shared with trucks carrying explosive materials as evident below.

As a result, local drivers compensate by driving on whichever side of the road they believe is available to them.

Ray commented: “There was no ‘right side’ of the road.”

When Ray and Dave arrived in the town of Quiruvilca, 12,500 feet (3,800 meters) above sea level, they were welcomed by their hosts and given comfortable accommodations. They learned the name “Quiruvilca”, from the Quechua language, meant “sacred tooth,” which locals said referred to the protruding land feature on the center-left of the photo below.

In the town of Quiruvilca, Ray and Dave sought out mineral specimens from the miners by visiting their homes (below), but it was very hard to find any, as most are bought by runners on an almost-daily basis and sold to Peruvian dealers.

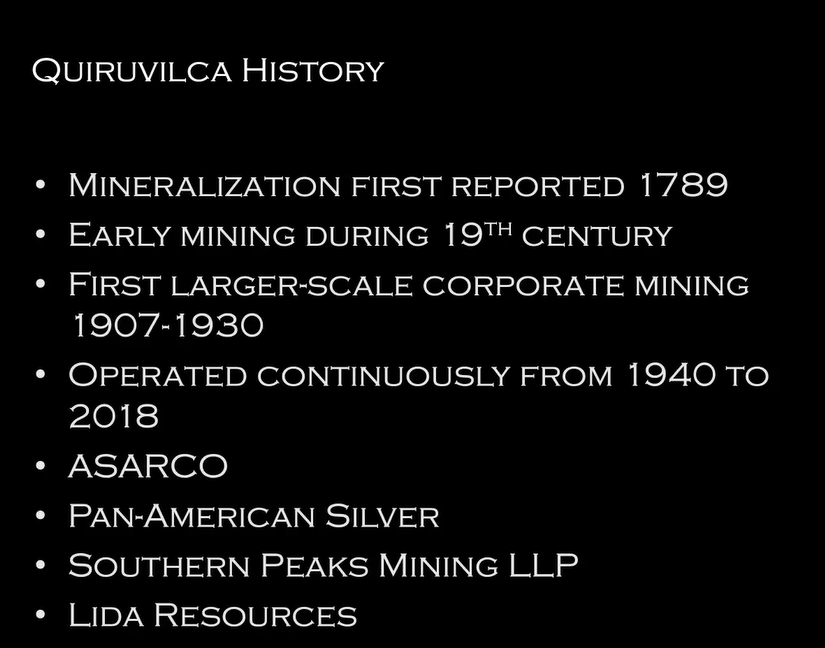

History of the Quiruvilca Mine

Information about small-scale mining in the Quiruvilca district first became public in 1789. Fast forward over a century and its corporate production had become large-scale by the second and third decades of the 20th century. Ray pointed out that because metals are a commodity, interest in metal mining rises and falls with the market prices for the mine’s copper, lead, zinc, and silver.

Currently the mine’s operations are paused. There are reports of a few individual mineral specimens dribbling out, but the commercial operations are on care and maintenance.

Geological Overview

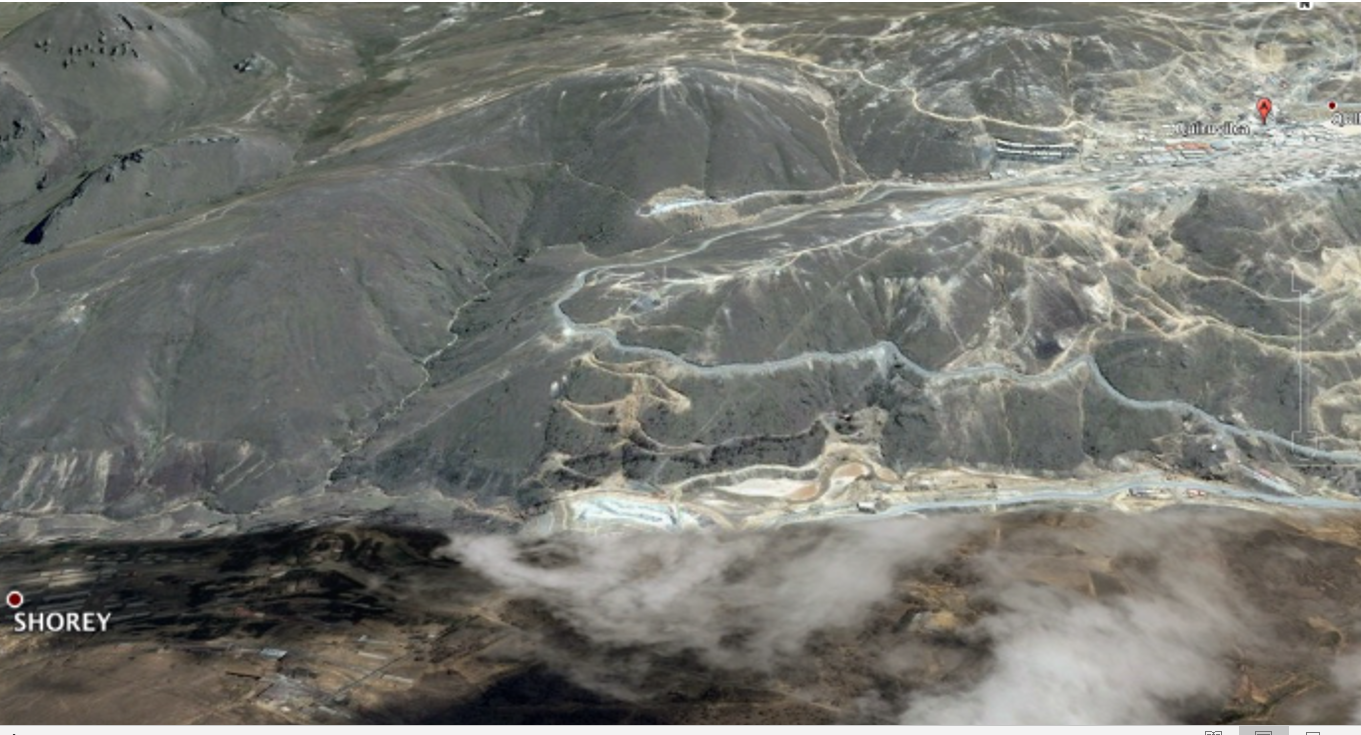

Below is a Google Earth view showing the town of Quiruvilca in the upper right, while the underground workings span much of the photo area. The facilities and processing operations are at lower left.

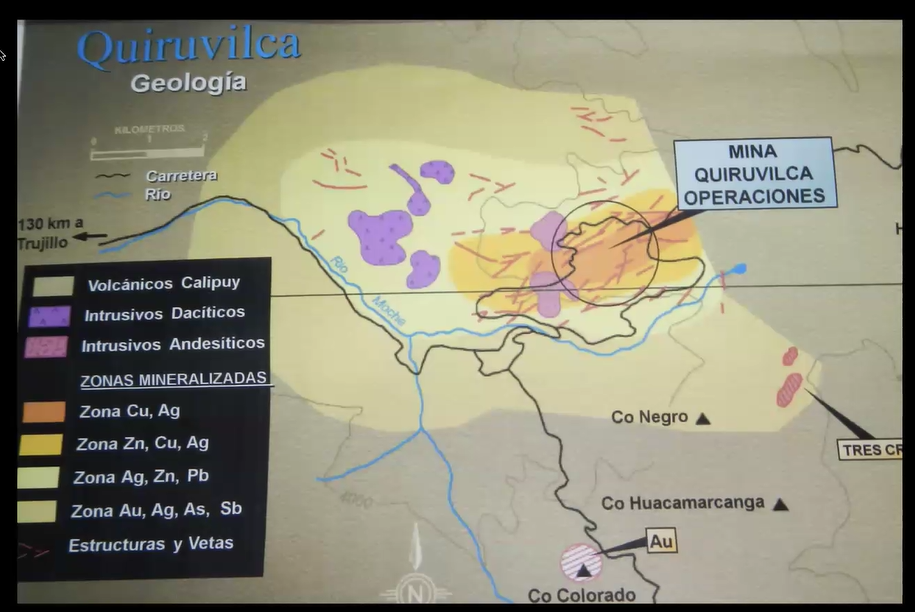

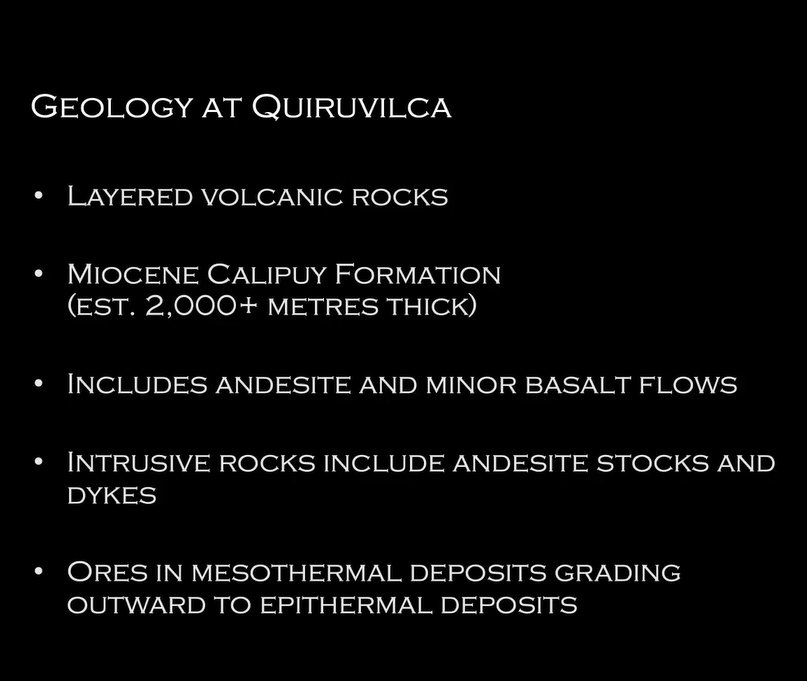

In the above image, the color chart shows the specific mineral content of the four zones in the illustration, from orange to yellow.

In the prior illustration, the innermost zone (designated 1) is represented within the circle as orange. This is the enargite (copper) zone – historically, this area is where the early mining was concentrated and where the famous orpiment specimens were discovered, along with realgar and world’s best hutchinsonites.

This zone also produced a wide range of other specimens including pyrrhotite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and quartz.

The transition zone (2), Ray noted, is also known as the copper zone and is represented as deep yellow. The lead-zinc zone (3) has a concentration of those two metals and is represented in the above illustration as light yellow or cream color. The stibnite zone (4), in beige, has not been actively mined, but stibnite specimens have been recovered there.

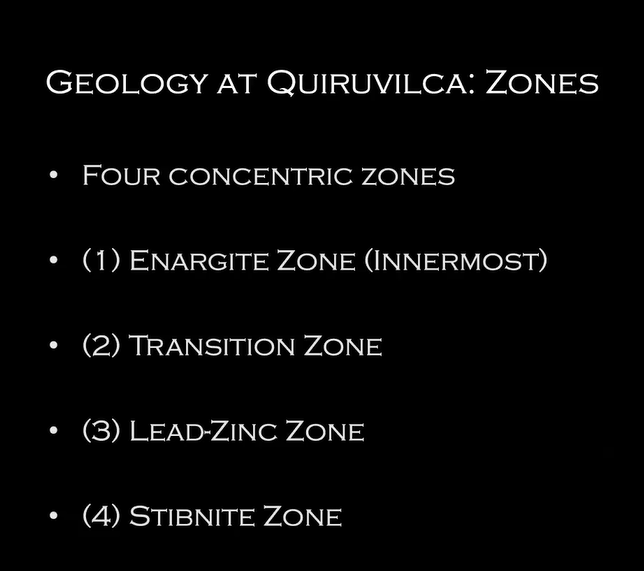

As a further explanation of the geology of the Quiruvilca mine, Ray provided the following sketch which is a look back and summary.

Ray commented on the age of the Quiruvilca rocks – being Miocene (10-20 million years old), geologically, these are very young rocks and young intrusives.

Underground Workings

Southern Peaks graciously provided Ray and Dave guided days underground, with the goal of visiting active underground workings that might produce interesting mineral specimens.

In the photo below, the mine’s geologist and supervisor were briefing Ray and Dave on where they were headed and what to expect. Note the timbers just beside them to be used for shoring up tunnels and the ongoing need to replace aging tunnel supports. Safety above and below ground was always priority number one.

At the time of their visit, operations were running 24/7, with three shifts per day and small teams of 6 workers each digging at 60 separate working faces. The miners filled cart after cart with ore, which was then transported on rails to the surface. In total, approximately 1,000 people were working at the Quiruvilca mining/milling/office complex.

For the mine workings in active use, the corrosive water required the replacement of the rails every 5 years and of the timber-supports every couple of years. Below Dave is examining some chalcopyrite and sphalerite.

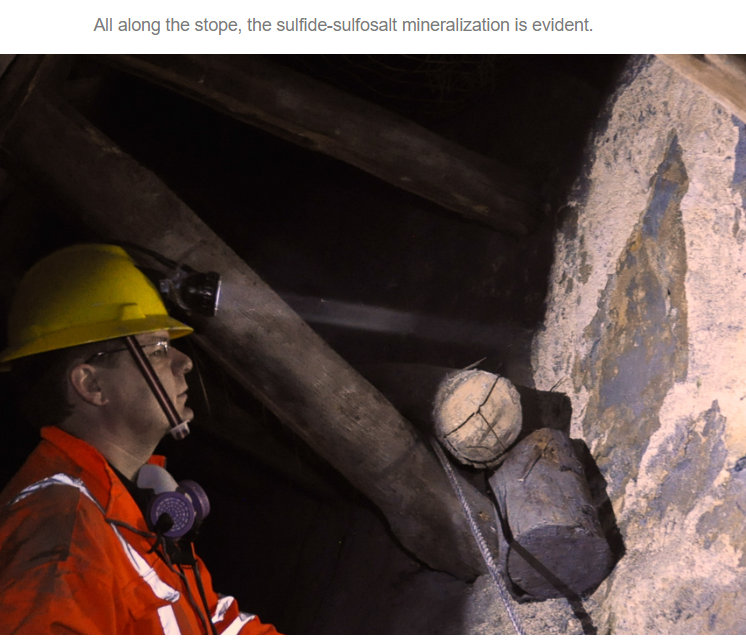

Similarly, below, Ray’s light is showing mineralization but sadly no pockets or vugs that might provide some good mineral specimens.

Ray said he found the small pocket pictured below containing chalcopyrite, tetrahedrite, and micros, which were interesting but not fine specimens worthy of extraction.

The Minerals at Quiruvilca

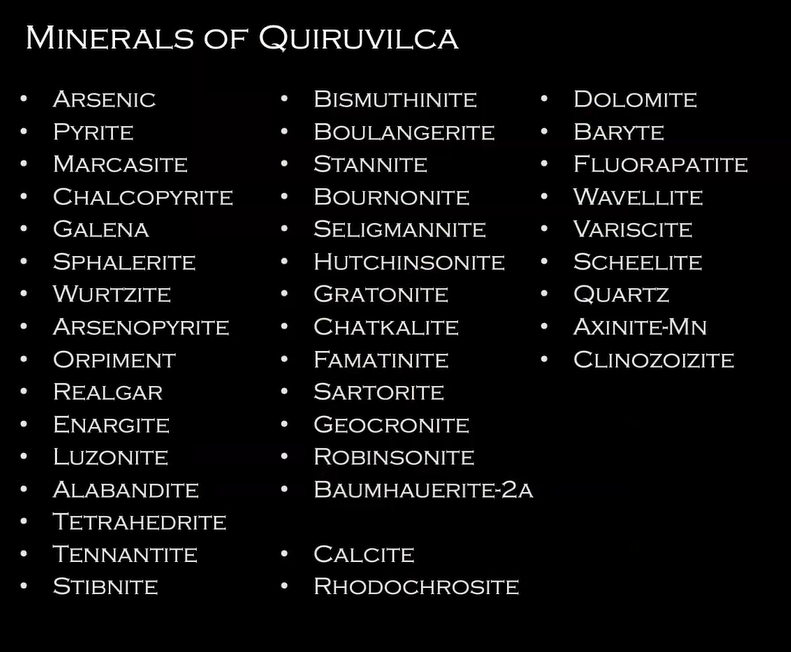

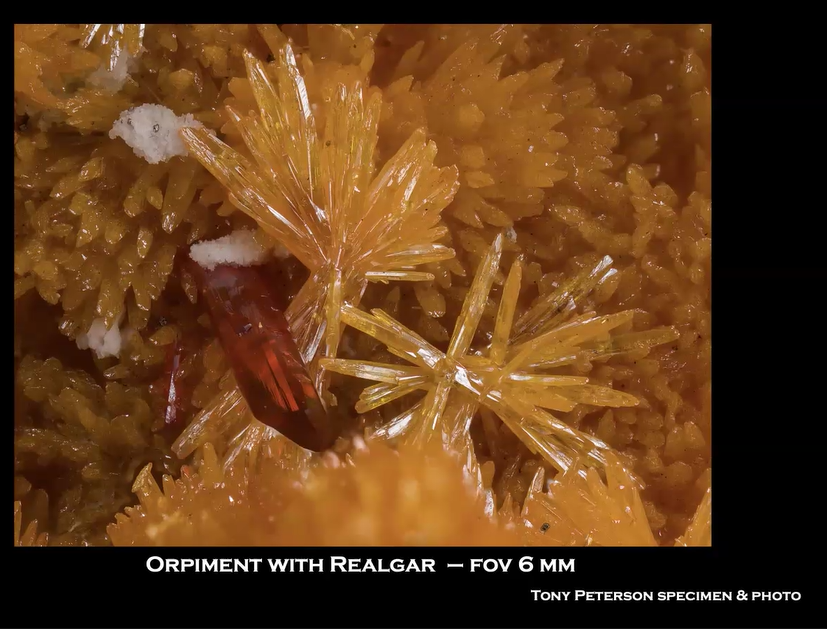

As shown below, Ray listed the minerals found at Quiruvilca. As one can see, the mineralization is dominated by primarily sulfides and sulfosalts (from pyrite, down to baumhauerite).

Below a second list identifies the minerals that are of special significance as fine mineral specimens coming from the mine.

The pyrites that came out of this mine in the early years when it was first recognized for these high-quality specimens, Ray said, were probably at that time the best octahedral pyrites in the world.

Please note that the following photos are by various photographers, and the copyright for each belongs to the credited photographer. The photographers kindly gave their permission for these photos to be used in the presentation slides, but these photos may not be further reproduced without their written consent.

When mineral dealers and collectors first came to know of Quiruvilca in the 1970s, it was famous for its octahedral pyrite crystals.

Over the years, pyrite crystals exhibiting many crystal forms have been recovered, Below are dodecahedral pyrite crystals with octahedral modifications, on quartz.

Quiruvilca is known for having produced some of the finest and largest enargite crystal specimens from any locality.

Below, the enargite (silver colored) crystals are mixed together with pyrite (golden colored).

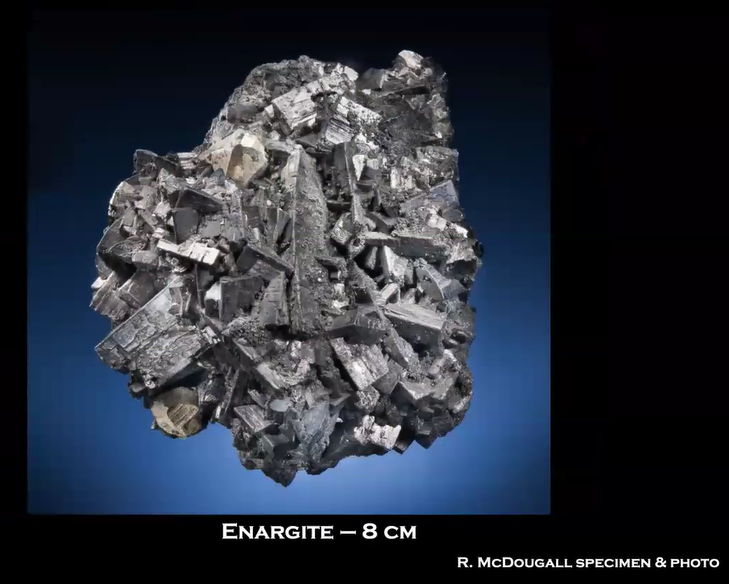

Quiruvilca is also world famous for superb orpiment crystals, mostly from historical workings. Orpiment is a very fragile mineral, easily damaged (even a finger pad gently touching a crystal can leave it damaged!). As a result, it is always hard to acquire high-quality orpiment, and even more so when those specimens have been collected by miners who may not be as careful as experienced collectors.

Orpiment is also light sensitive and so collectors need to keep orpiment specimens in the dark to preserve their distinctive orange/golden color. Below are two examples of a beautiful, large orpiment specimens that did make it into the hands of a professional collector and were properly cared for and preserved.

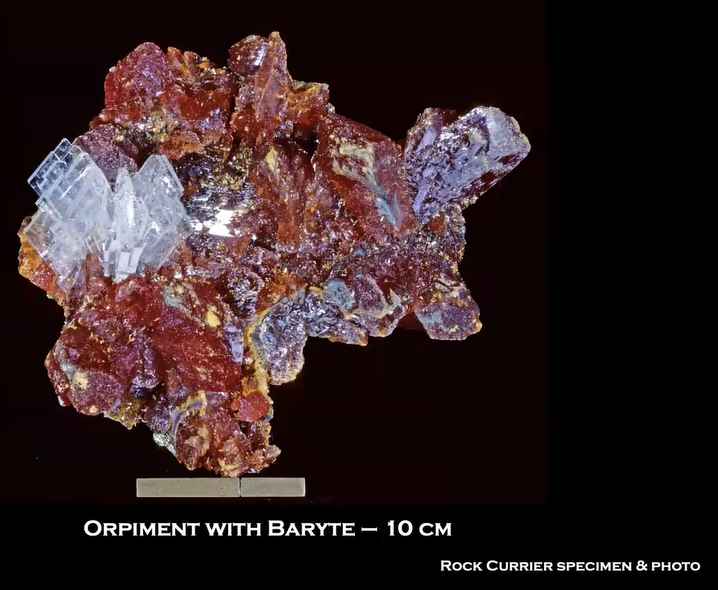

Orpiment also has been found in micro form. Below is a 6 mm specimen, along with deep red crystals realgar, beautifully photographed by Canadian collector and mineral photographer Tony Peterson.

To learn about and see beautiful specimens of the other significant minerals from Quiruvilca, check out Ray’s MSDC YouTube video. There you will find world class examples of hutchinsonite, along with excellent specimens of bournonite, baryte, tennantite, arsenopyrite, jamesonite, native arsenic and others. Ray also explained variations on mineral labels that may accompany specimens from Quiruvilca.

Overall, Ray conveyed a sense of what Quiruvilca is like, and how hard it is to find fine mineral specimens there, giving context to just how amazing good specimens from Quiruvilca really are. We tend to lose sight of this when we see so many fine minerals available at shows and online, but all these specimens, from all over the world, have a story and have come a long way for us to be able to enjoy their beauty,

Ray gave abundant thanks to Adolfo Vera and all at Southern Peaks who made the visit possible, and to Ray’s friends and colleagues who lent their support to make this presentation possible. Some are identified in the slide below.

MSDC President Kenny Reynolds then thanked Ray for his superb talk and opened the floor for questions. Be sure to listen to this session to learn Ray’s appreciation for the fleeting nature of all dig sites, and his other insights about minerals and the collecting community.