Southern Greenland's Mineral Resources and the Ivittuut Cryolite Mine

Synopsis by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

Thomas Hale, familiar to most MSDC members from a prior presentation, updated everyone on his busy 2023 world travels, field work, and starting his academic engagement in the University of Delaware’s Ph.D. program. He summarized this January 3, 2024 presentation by saying: “Tonight I’m giving a talk on some of my research on Southern Greenland and its mineral resources. Specifically, I will look at the cryolite mine which is a case study I am working on.”

He highlighted the three main parts of his talk as follows: Part One is a review of South Greenland’s rich mineral resources and the social, environmental, and political challenges that need to be addressed if Greenland is to achieve a sustainable mining economy. Part Two is a historical overview of the Ivittuut Cryolite Mine, Greenland’s sole successful mining operation. Part Three updates the nation’s key policy developments and provides salient literature for understanding Greenland’s mining sector.

Thomas said he hopes this presentation informs his audience’s interest in understanding and unlocking the country’s mineral resources. And, he added, his goal is to contribute to a sustainable future for all parties, including for indigenous communities.

A note to readers: The purpose of this Program Report is to encourage those interested to view MSDC’s YouTube video of Thomas’ 53-minute presentation. Readers can access it by clicking on the following link: Greenland's Mineral Frontier - Thomas Hale (youtube.com)

Summary of Field Work

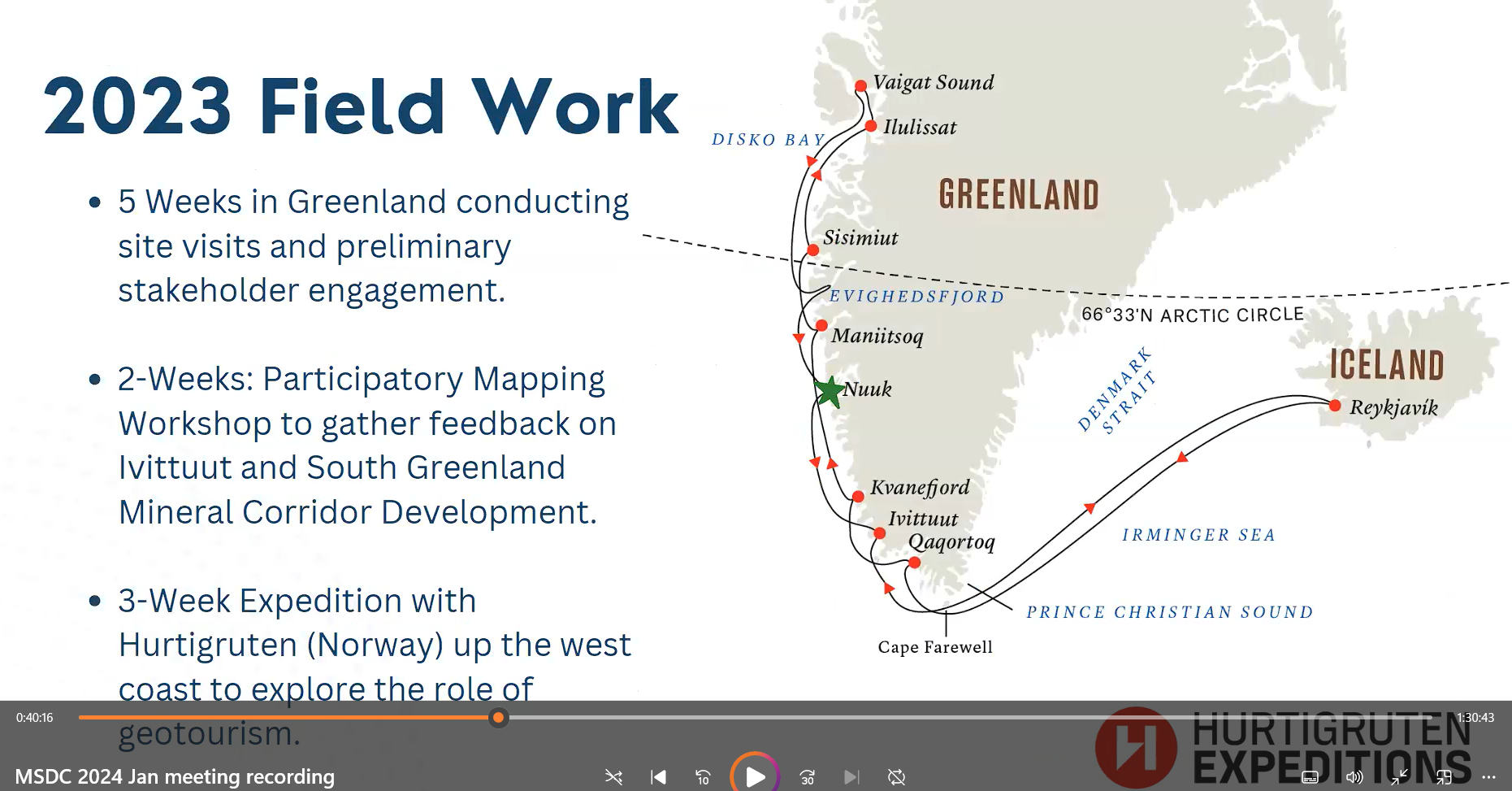

Thomas’ five-week visit to Greenland came about by way of an August 2023 flight from Reykjavik, Iceland. The map below traces his travels by boat between eight major stopping sites. Given that Greenland is the world’s largest island that is not a continent, its sparse population of 57,000 people, the lack of connecting highways, and the prohibitive expense of travel by helicopter, Thomas’ journey was primarily by boat. Additionally, 80% of the land is covered by ice so the people live on the western coastline and on rocky outcrops, as shown in the photo below.

He gave credit and thanks to Peter Barfoed, the acknowledged guru of the Ivittuut mine, for generously sharing his in-depth knowledge of the mining industry and the cryolite mine. It operated from 1854 to 1987 and was the only commercially successful mining operation in Greenland’s history. The roadblocks to successful mining in Greenland are many and complex, as Thomas made evident throughout his talk.

Also noted in the illustration below, during his five-week field work, the first two weeks focused on the southwest region of Greenland, the island’s Mineral Corridor Development.

Greenland Overview

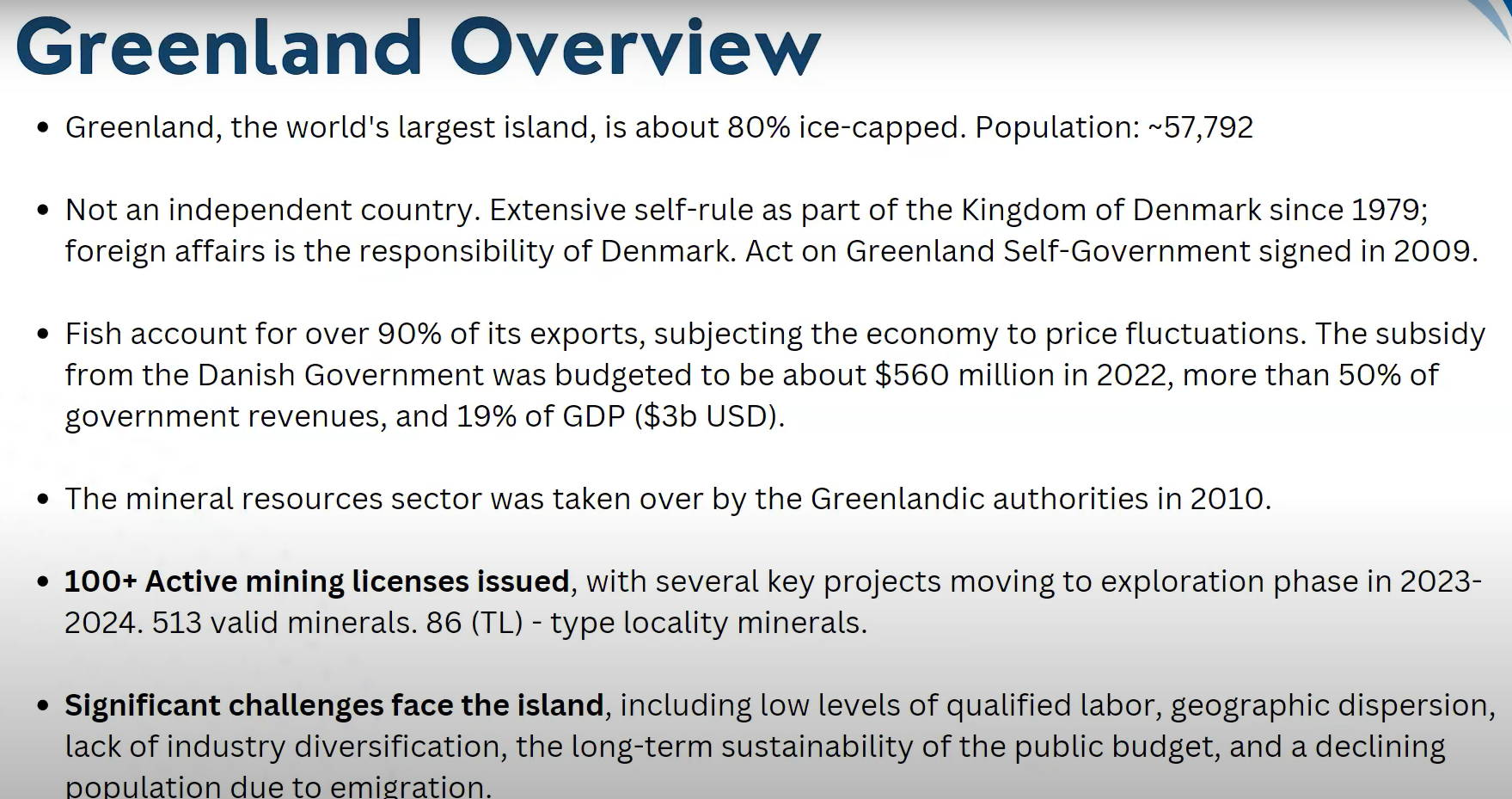

The following “Overview” identified some of the major factors which contribute to making industrial mining so difficult. Thomas unpacked each, as well as other serious challenges. Those conducting business negotiations, for example, often do not speak the same language, literally, Danish vs. native Greenlandic dialects, with Kalaallisut (in Western Greenland) being the most common.

The disconnects between the skills required by foreign mining companies and the skill sets of the native peoples are extensive, as noted in the above “Overview.” “But what makes Greenland very exciting for mineral collectors is the extensive number of minerals, 513, and most importantly, the 86 type locality minerals.”

Greenland Geology

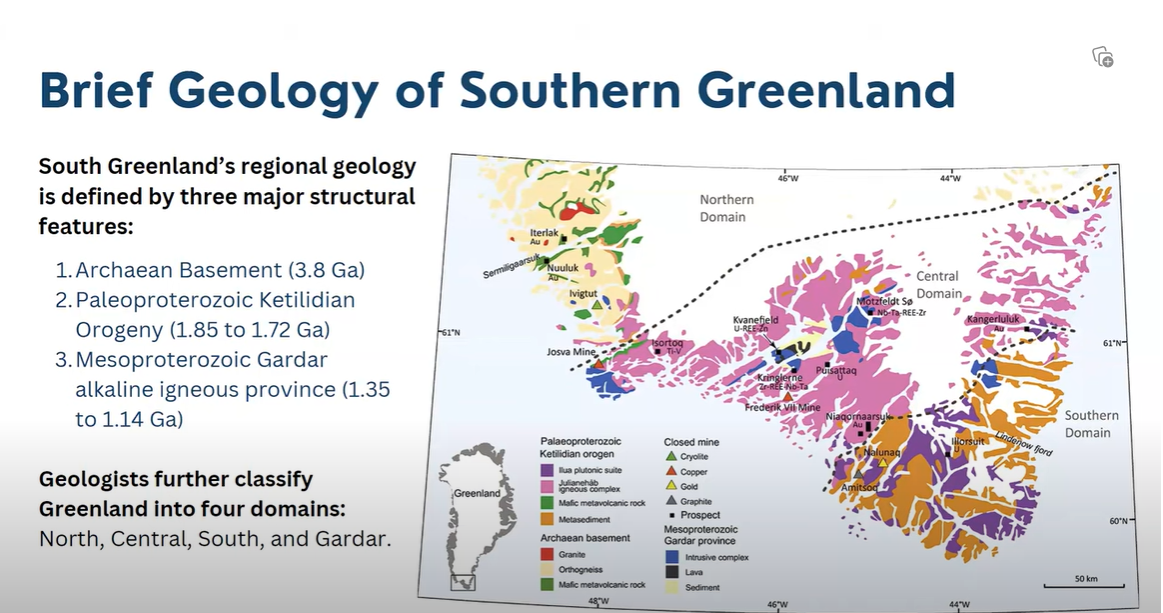

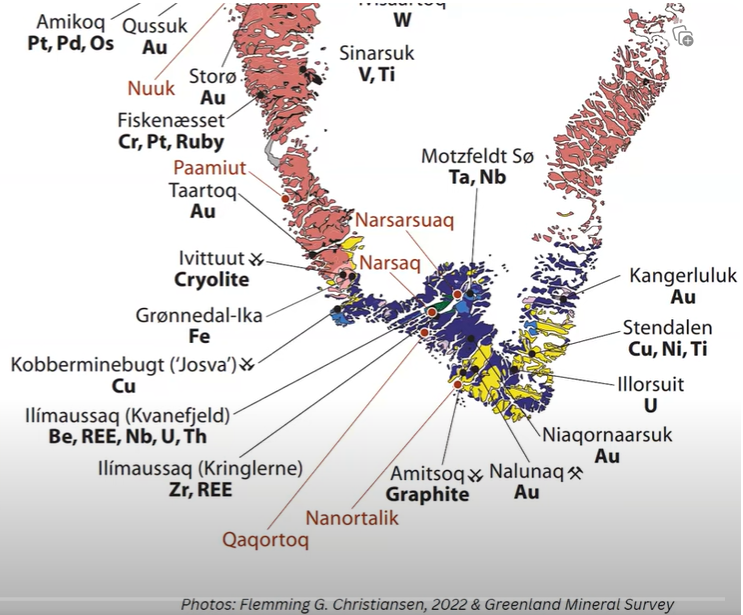

Thomas then provided an overview of the geology of Greenland’s southern sector, the only areas which have been thoroughly studied. He noted that there are three major structural formations as illustrated in the map below: the Archaean Basement (top left in yellow, red, and green), the Paleoproterozoic Ketilidian Orogeny (middle in purple) and the Mesoproterozoic Gardar province (middle in blue).

“It is this third province, the Gadar alkaline igneous region where one finds all these really interesting minerals and deposits which have been injected. These minerals are what has captured the interest of mineral collectors and the mining industry, eager to tap into these resources.” So, the Gadar is really Thomas’ focus for his presentation. When you hear about Greenland’s mineral resources, he said, this is the region people are talking about.

The illustration below provides information about where the most interesting minerals are found, including the rare earth elements (REEs, bottom central, in blue), and cryolite at the now-closed Ivittuut mine (bottom left in light brown). He noted the locations for copper, nickel, gold and graphite “which have not been extracted at an industrial scale.” It is the inhibiting factors, explained above, that have prevented profitable mining. So these rich mineral resources remain untapped, and today, “that’s what creates a lot of interest.”

Mineral Resources of Greenland

For the U.S. mining industry, it is the REEs or minerals which hold the strongest interest for further exploration.

History of Mining in Greenland

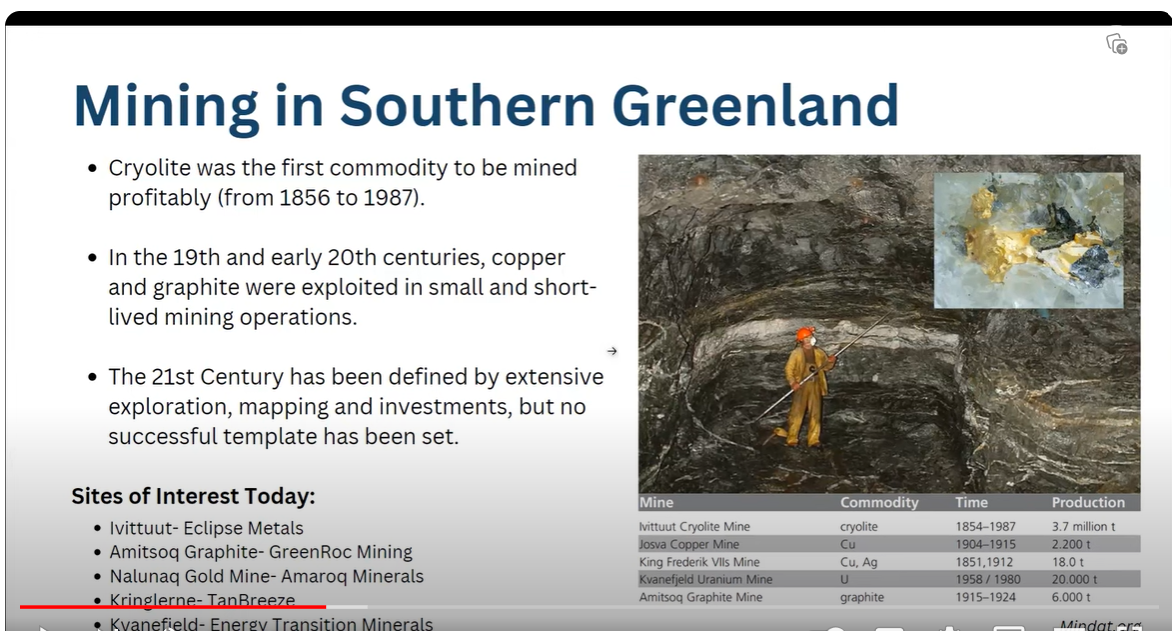

As noted earlier, the mining of cryolite has been the only successful mining operation in Greenland and that lasted for 133 years. Gigantic tonnage was extracted to support diverse industries such as ceramics, abrasives, metals, glass, and pesticides.

Copper, gold, uranium, and graphite were also mined in much smaller quantities and for shorter durations, as noted in Thomas’ graphic below. To learn which of these elements tops the list for the U.S. interests, go to the video tape to hear Thomas’ view. Click on: Greenland's Mineral Frontier - Thomas Hale (youtube.com). Hint: the key element has something to do with nuclear energy and has resulted in considerable ongoing environmental challenges for Greenland.

Additionally, the above slide at the bottom left identifies five industrial mining “Sites of Interest Today.” Thomas explained that each of these is in geographic areas which overlap with the mines listed on the bottom right, which were short- lived and closed many decades ago.

Interesting Mineral Sites for Collectors

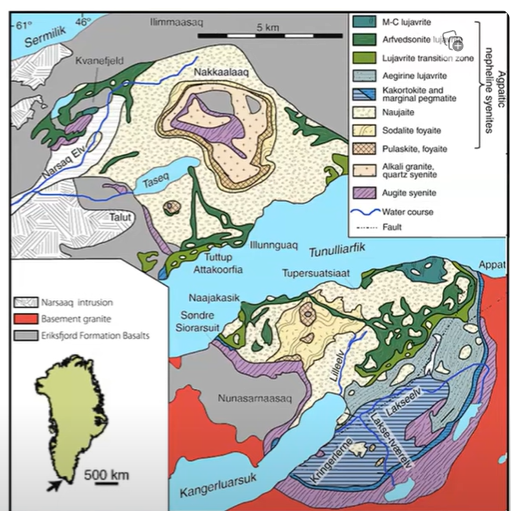

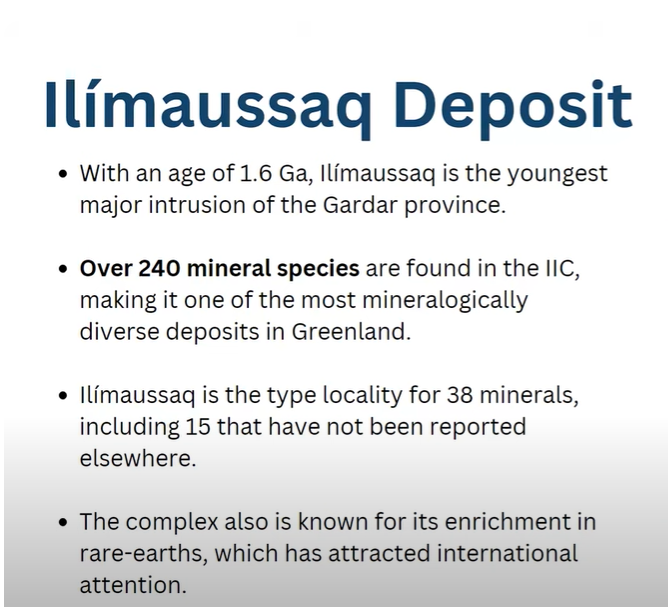

The map immediately below shows the location of the Ilumaussaq deposit, near the center of the mining areas of interest, which also are the most interesting for mineral collectors. The Ilumaussaq mining area consists of two sites, to the right of Narsaq on map below. They are the two black areas, divided by a fjord, separating two rare earth mining sites owned by two distinct mining companies. These mining areas are shown in more detail in the more colorful geologic map below.

Thomas’ description of the diversity of minerals, including 38 type locality minerals, will appeal to collectors, including fluorescent enthusiasts and 15 minerals reported nowhere else on Earth.

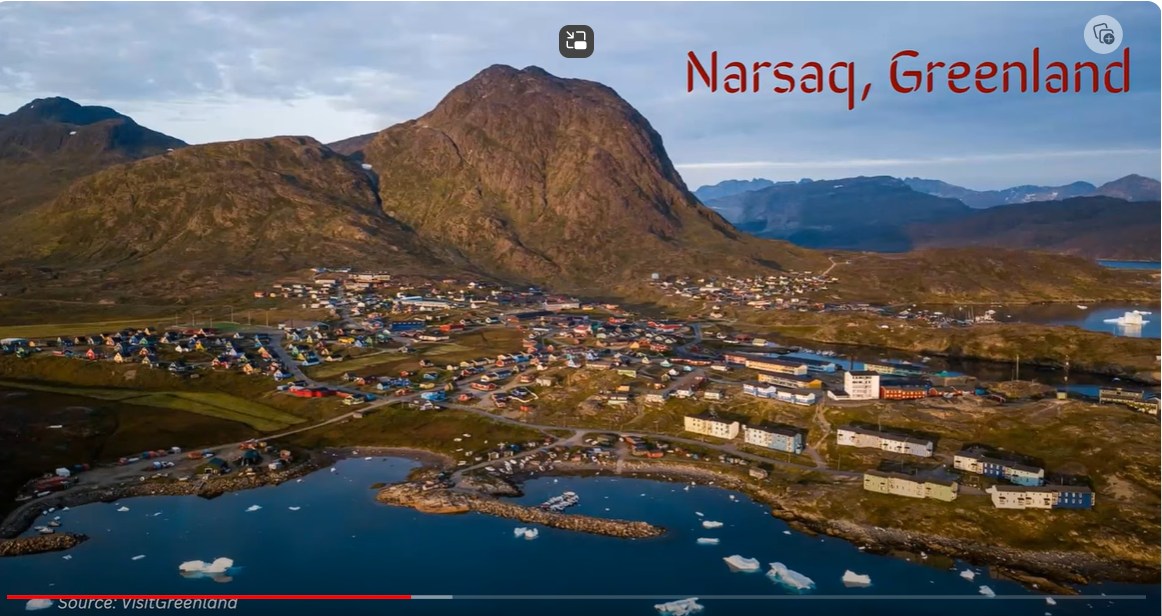

The community that serves these two REE mining areas is Narsaq, shown below. Thomas described this community as very challenged by transitory foreign miners and toxic mining debris which is dumped into the lake located behind the mountainous bluff pictured below.

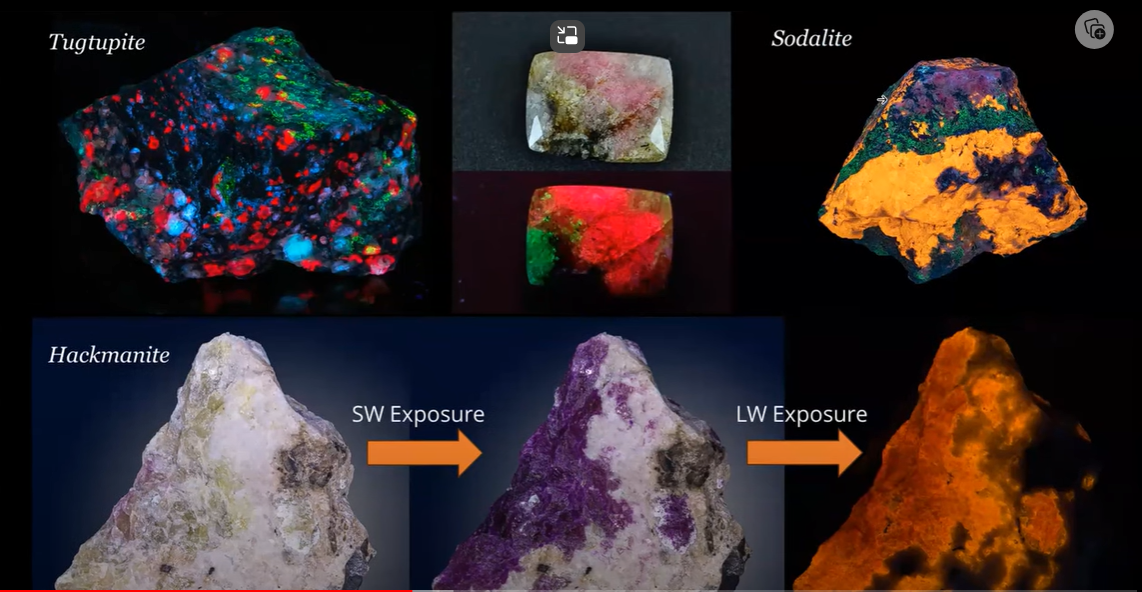

Below are a few examples of the fluorescent minerals commonly found in this area and their different appearances when exposed to short- and long-wave UV light.

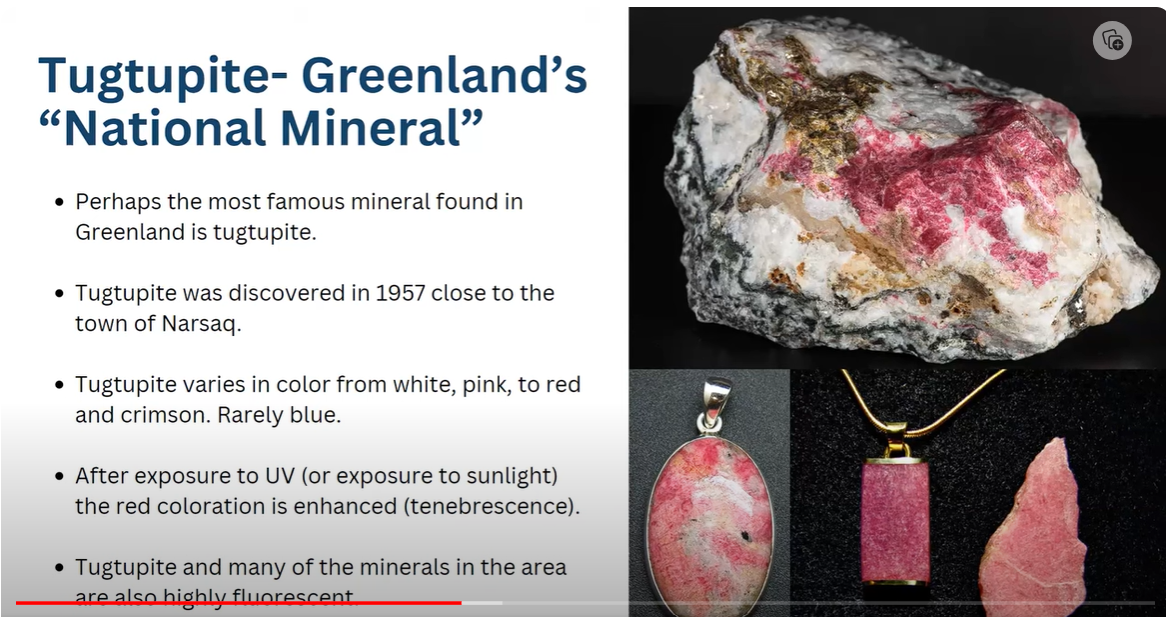

Many of the non-fluorescent minerals found in Greenland are used for cabs and jewelry, rather than for museum-quality displays. Tugtupite, for example, is a fluorescent mineral that is also the national mineral of Greenland.

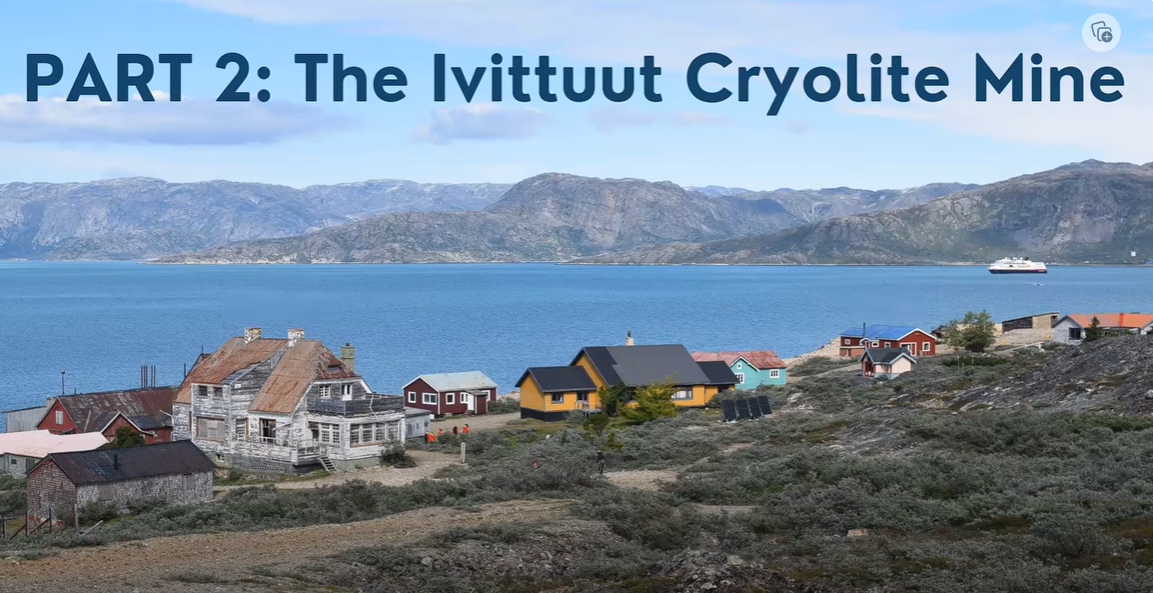

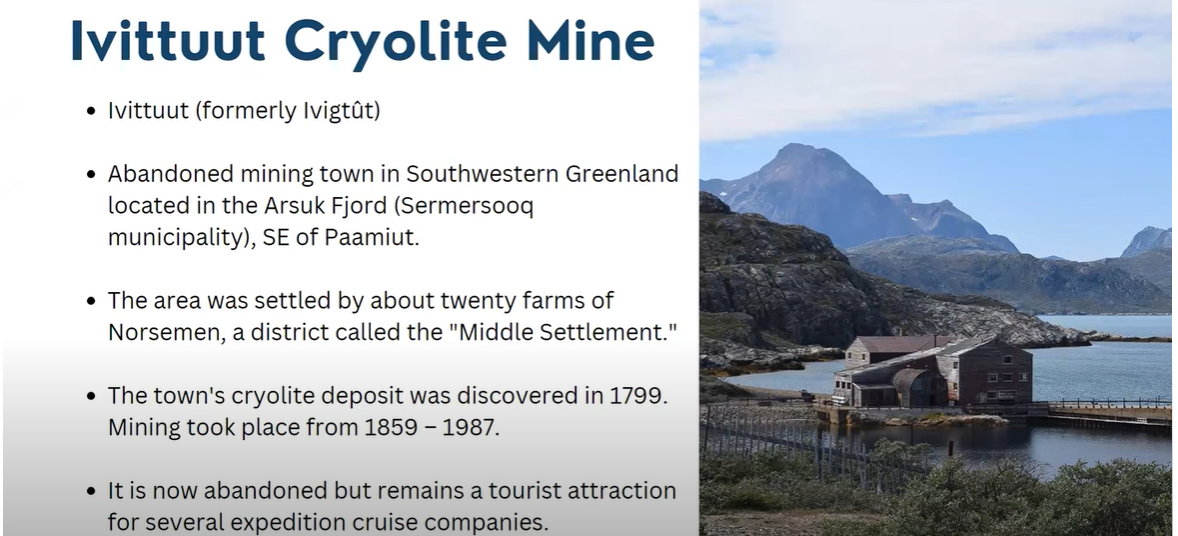

Part Two of Thomas’ three-part talk focused on the Cryolite mine and its town, pictured above, which is one of many ghost towns where mining once blossomed. Thomas shared his experiences there with another visitor who decades ago helped run the mine and shared his fond memories of the once booming area.

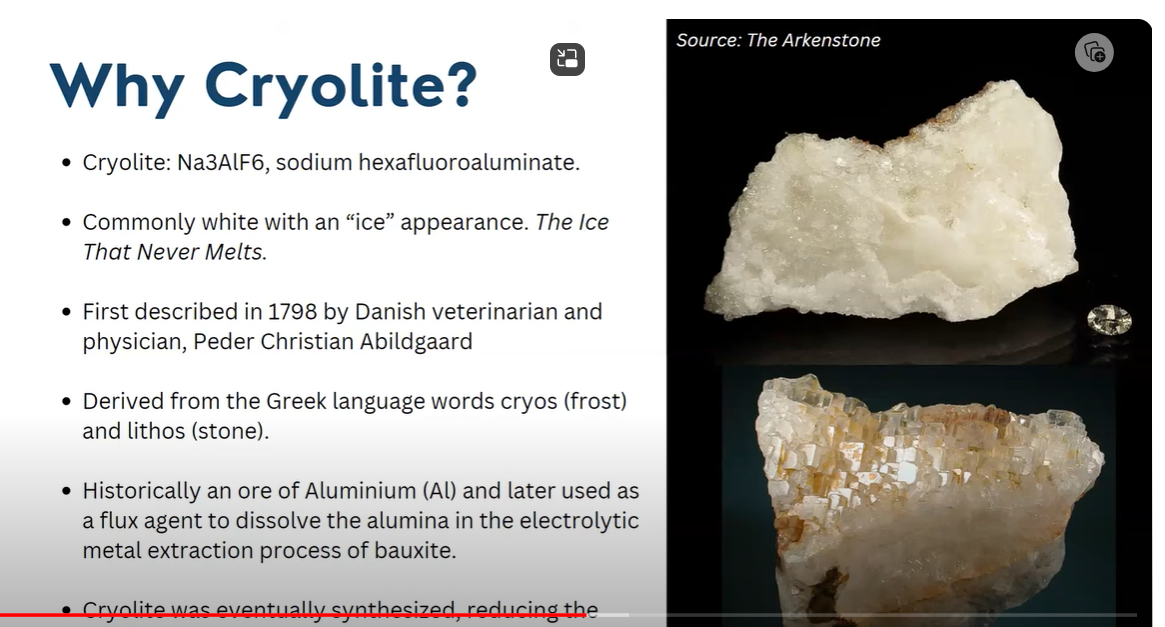

Thomas explained the industrial uses of cryolite, including as a flux, and the origin of its name (frost stone), as noted below. Importantly, he added, the Greenland mine was the worldwide sole source for cryolite, which gave it strategic importance, especially during WWII. Eventually, the need to mine natural cryolite was replaced by a manufactured, synthetic process.

While at the Ivittuut mine, Thomas said he helped visitors distinguish between cryolite, which is scratchy, from another white common mineral, quartz, which is comparatively smooth. Also, he noted, actual crystals of cryolite, as shown in the bottom photo above, are rare.

Thomas shared that one of his strong interests is helping to resolve disputes which arise from conflicts between mining interests and environmental and cultural interests. While visiting the two-person Danish military outpost at Gronnedal, to the north-east of the Ivittuut mine, a previously unknown conflict came to light.

The military post was established historically to protect the Ivittuut cryolite mine. During Thomas’ visit, he shared with the soldiers the historical contract paperwork and satellite imagery (MEL 2007-45) showing that the mine and fort connect by the long Route One road along the coastline. The military personnel had not previously seen that map with the result that the military became aware of its responsibility to protect the wide swath of inactive mining areas further inland east of the two-person military base.

The result of this new awareness was that the military immediately shut down the road and the access to the broader swath of the mining territory.

Environmental and Social Issues

An example of a large-scale environmental problem stems from the mining and shipping of cryolite from a deep pit next to the Arsuck fjord coastline. The photo below captured its appearance in the 1970s and 80s. Some of the excavated minerals included lead and fluorite and accidently ended up in the waters which have been toxic to everything living in the fjord. This problem existed from the mine’s origins through to its closure. The pollution continues to this day due to the leaching of the mine’s tailings, and impacts the 75 residents of the town.

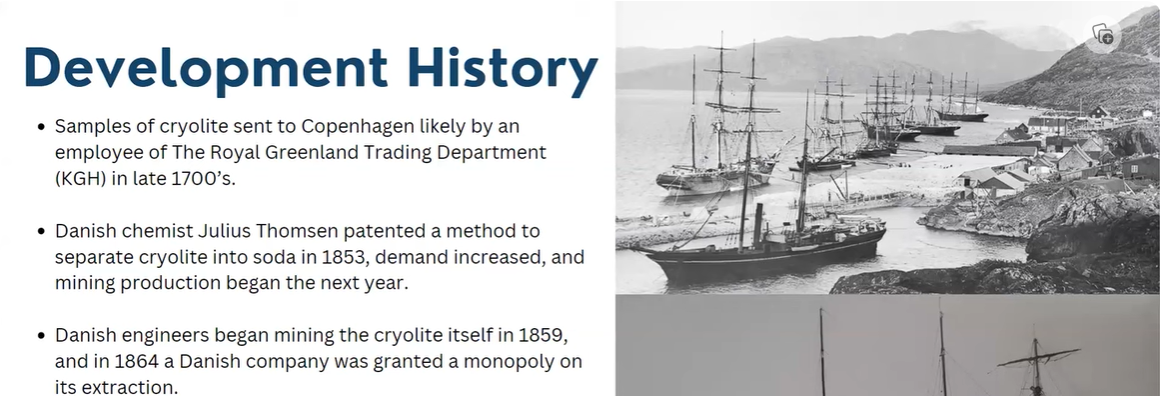

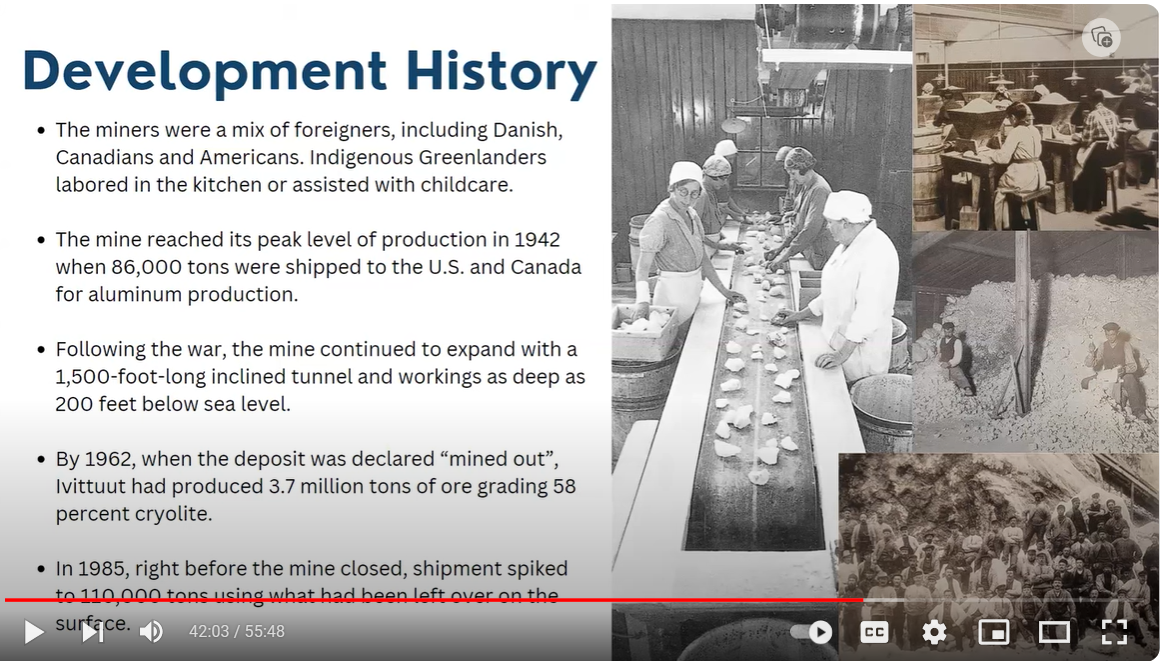

Thomas then presented information on the historical development of cryolite mining.

Throughout those many decades, he noted, the native Greenlanders, the Inuit peoples who lived near the mines, were not invited to work there other than for providing childcare or cooking for the miners and their families. So that peripheral employment, economically speaking, left the Inuit peoples essentially out in the cold for the entire life-span of the Ivittuut and other mining operations.

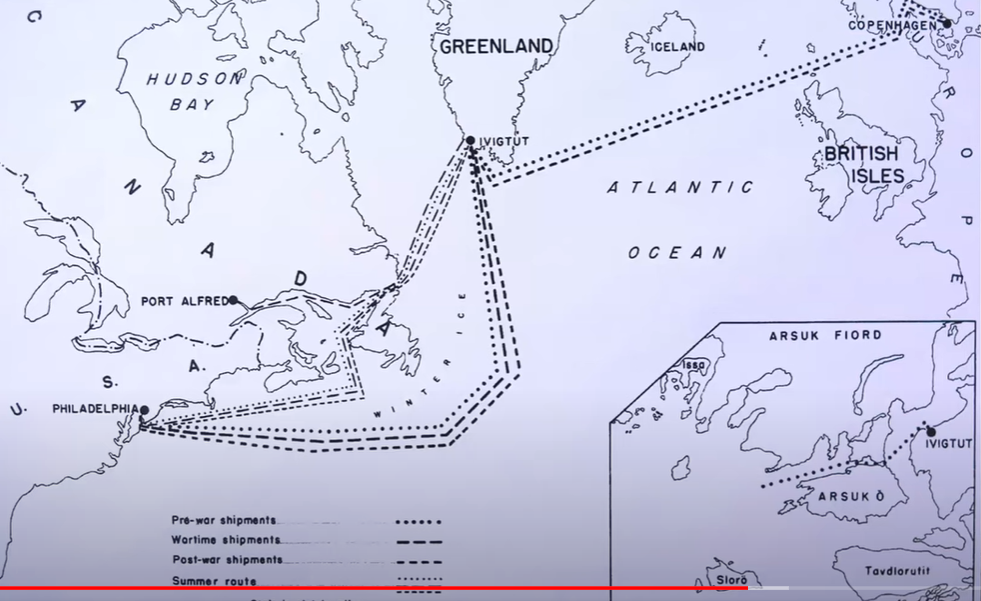

Among those who did benefit from the cryolite mining were the worldwide community of metal workers and the DuPont chemical company based in Delaware, located a little south of the Philadelphia port as shown below.

As an interesting aside, Thomas, a coin collector, shared that he is looking for a 1922, 50 ore (cent) Danish coin shown below, commemorating the “Ivigtut Kryolith Brud” mine, central to this evening’s presentation.

The peak production year for cryolite was 1942 when the U.S. desperately needed it for production of aluminum for building the planes essential for the WWII effort. Pictured below is a montage of activities related to processing the cryolite.

Thomas wrapped up Part Two of his talk about the cryolite mining site by noting that although the Ivittuut mine has been closed for decades, in more recent years, there is a new development for mineral collectors. With the increased melting of Greenland’s snow cap, more of the untouched rock is becoming exposed which peaks the interests of mining companies and mineral collectors alike. But for collectors, Thomas said he saw a lot of interesting minerals just sitting on the surface, especially siderite and cryolite as shown below.

There are also specimens for micromineral collectors as well. However, their presence of course, including thomsenolite and pachnolite shown below, is not obvious.

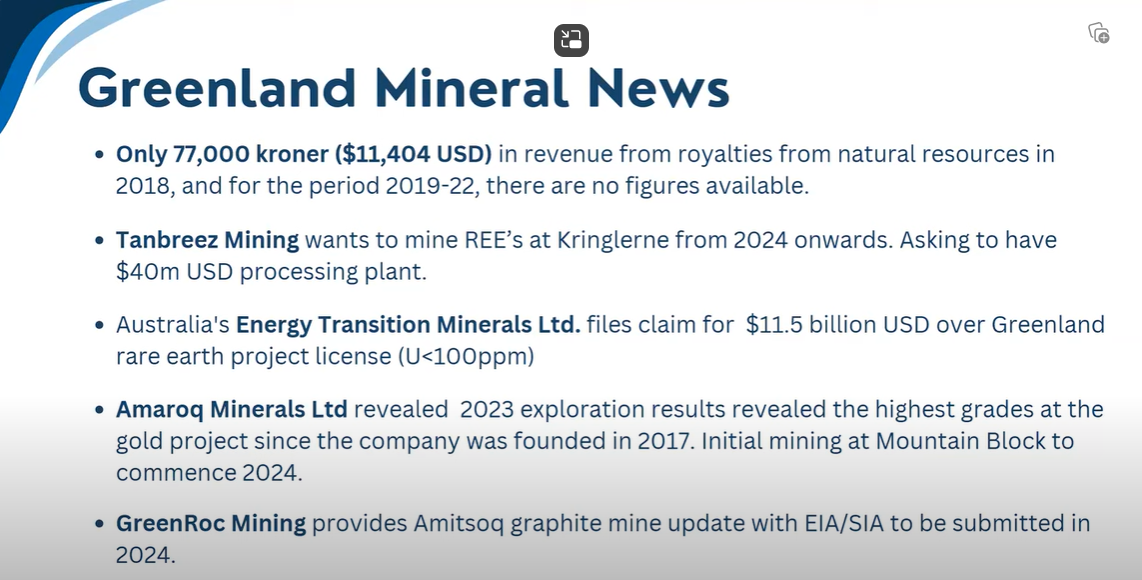

“Should you invest in mineral development in Greenland right now” Thomas posed. He responded: maybe you should hold off for a while. From an article cited below, the most recent data available is for 2018 and it indicates the government of Greenland received only $11,404 USD in royalties from its natural resources. For the following years, 2019 through 2022, no data was available.

Over the decades, mining companies have often staked out and filed claims for mining various metals, but their efforts have not proven fruitful. For 2024, as noted below, claims continue to be filed, including for REE, gold, and graphite mining. China, Australia, and U.S. mining companies have shown extensive interest. The mineral deposits are there, but given all the environmental and other challenges, only time will tell if the mining will be successful.

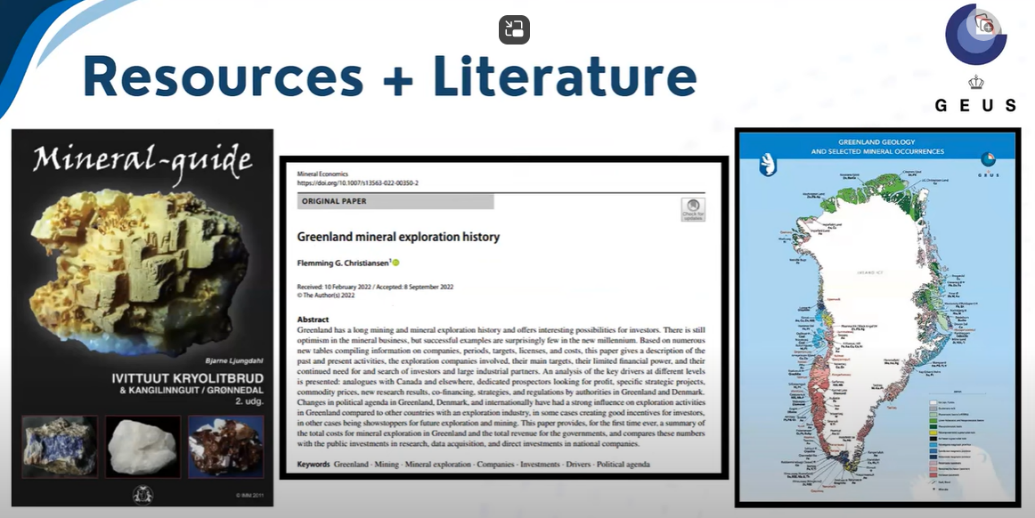

For readers interested in following up on Thomas’ presentation and learning more about Greenland’s mineral resources, he recommended several resources, noted below.

Thomas singled out the above middle resource, a scholarly article by Dr. G. Christensen Flemming, “Greenland mineral exploration history,” published in Mineral Economics in late 2022. As an open-source journal, it is readily available and easy to access.

The Mineral-guide, to the left, is available only in Danish. To the right is a reference to GEUS, the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, a research and survey institute closely related to the University of Copenhagen.

Wrap-up

That concluded Thomas’ personal experiences and scholarly overview of Greenland’s mineral resources. He opened the floor to questions, of which there were many. They ranged from inquiries about the challenges of mining specific minerals, to relevant exhibits at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

We encourage interested readers to click on the link below which will take them to MSDC’s YouTube channel to view Thomas’ interesting and data-packed presentation (length 53 minutes).

Greenland's Mineral Frontier - Thomas Hale (youtube.com)

MSDC’s President Kenny and Vice President for Programs Cindy then thanked Thomas for his excellent presentation, which was applauded by the many Zoom attendees.