The Hope Diamond, the World’s Most Famous Cursed Gem

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

Legend has it that the Hope Diamond, often touted as the world's most famous cursed gem, was originally obtained in India and passed through the hands of various owners including many who seemed to face misfortune and tragedy. These circumstances led people to believe in a curse that surrounds this exceptional blue gem.

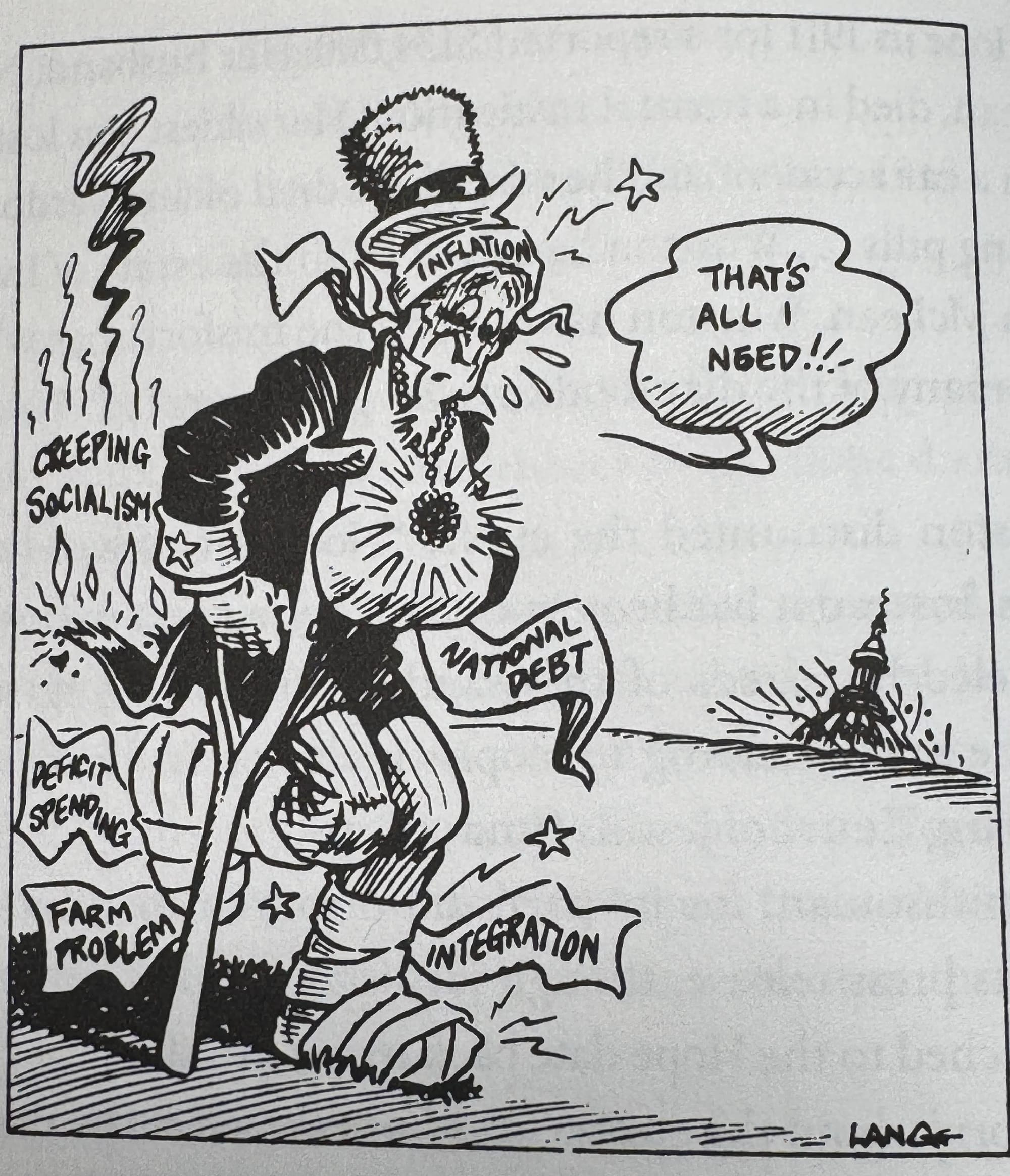

The legend was so prevalent in 1958 when the Smithsonian acquired the Hope Diamond that many Americans urged the National Museum not to accept the diamond in its collections for fear that the U.S. would be cursed.

The Cursed History of the Diamond

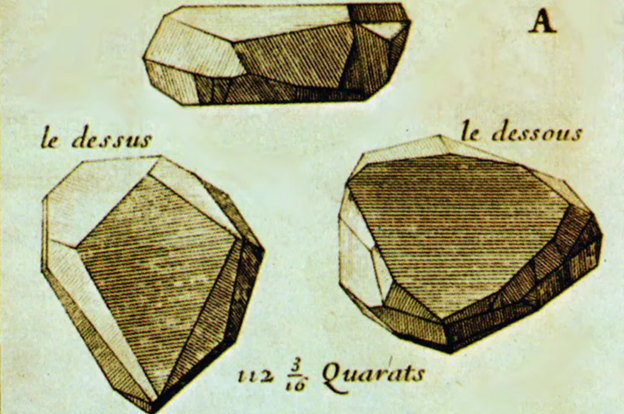

The diamond's dark reputation begins with its potentially unethical acquisition. According to historical accounts, the stone was originally stolen from a sacred statue in India, specifically from the eye of a Hindu deity in the temple of Sita. The legend suggests that a French explorer and merchant named Jean-Baptiste Tavernier visited India’s Golconda Sultanate and acquired the massive blue diamond in the mid-17th century through questionable means. It is unknown if he acquired it by purchase or theft. At this point, the gem was a crudely cut, triangular, flat, blue diamond of extraordinary size.

After returning to Europe in 1668, Tavernier met with King Louis XIV who was fond of beautiful and rare gems, especially diamonds. In December of that year at a meeting in Versailles, Tavernier shared a collection of diamonds collected on his recently completed trip to India. Two months later, Louis XIV purchased the lot of more than one thousand diamonds, including a large blue diamond weighing approximately 115 (modern) carats.

In recognition of this transaction, the king honored Tavernier with the rank of nobleman. Tavernier wrote extensively about the gem before his death in Moscow the following year — when he was reportedly dismembered by a pack of wild dogs. While this account has not been documented (no evidence of how Tavernier died has been found), it establishes the foundational mythology that would follow the gem through subsequent generations.

Louis XIV and the “French Blue”

King Louis XIV ordered one of his court jewelers to supervise the recutting of the 115-carat blue diamond. He likely ordered the stone recut because of differences between Indian and European tastes in diamonds: Indian gems were cut to retain size and weight, while Europeans prized luster, symmetry, and brilliance.

It is not known who actually cut the diamond, but the job took about two years to complete. The result was an approximately 69-carat heart-shaped diamond referred to as “the great violet diamond of His Majesty” in the historic royal archives.

The 1691 French crown jewel inventory further describes the recut stone as “a very big, violet (the period term for “blue”) diamond, thick, cut with facets on both sides and in the shape of a heart with eight main faces.”

Formally known as the Blue Diamond of the Crown of France and popularly as the “French Blue,” this smaller recut stone, with its enhanced symmetry and additional pavilion facets, was substantially more brilliant than the original Tavernier Diamond. The French Blue was likely the first large diamond to be cut in a modern brilliant style.

The idea that the French Blue was cursed gained credibility with the misfortunes of Louis XIV. Five of his legitimate children died in infancy. And the king himself died in agony of gangrene in 1715.

Louis XV and "The Order of the Golden Fleece"

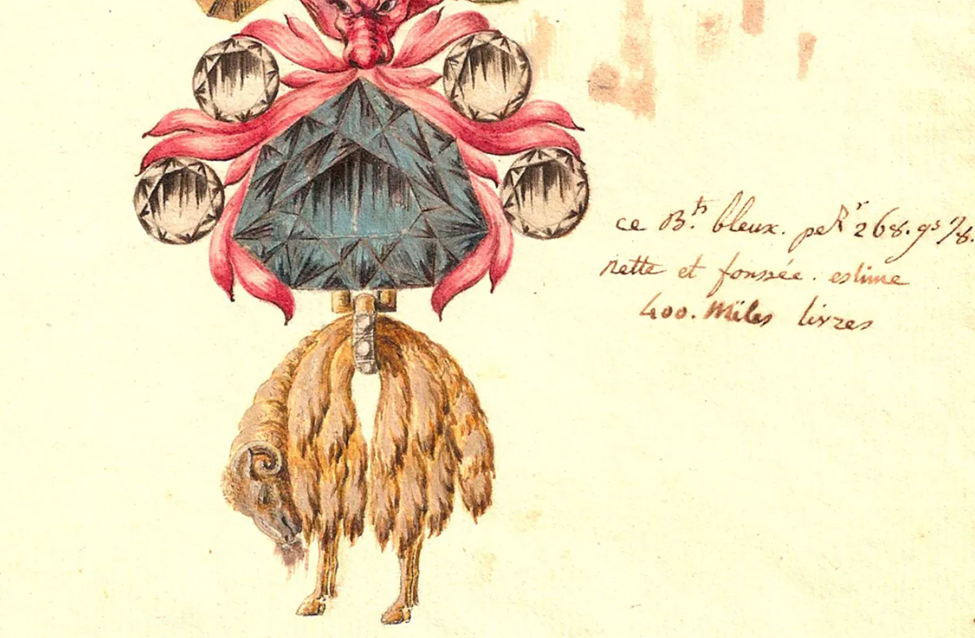

Louis XIV's great-grandson, Louis XV, inherited the royal jewels when he ascended to the throne. Around 1749, King Louis XV tasked the Parisian jeweler Pierre-André Jacquemin with creating an emblem of knighthood of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The finished emblem featured a number of spectacular gems, including the French Blue Diamond, the 107-carat Côte de Bretagne spinel (carved into the shape of a dragon and originally thought to be a ruby), and several other diamonds. It was rarely worn, functioning instead as a symbol of the king's power.

King Louis XVI and the French Revolution

During the French Revolution, King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette attempted to escape France, but were apprehended and returned to Paris. The French Crown Jewels, including the French Blue Diamond in the Order of the Golden Fleece, were confiscated by the revolutionary government at least partly out of fear that the king and his queen would use them to buy their freedom.

The gems were moved to the Garde-Meuble, the Royal Storehouse, where they were put on view for the public once a week until 1792. On visiting days, the doors of the armoires would be opened and a selection of mounted and unmounted jewels could be viewed in special display cases.

On the night of September 11, 1792, a group of thieves climbed through some open windows and stole some of the French Crown Jewels. Authorities were not aware of the theft, so on the following nights, the miscreants returned to steal more of the jewels, but acted carelessly and loudly and ultimately were caught. By then, the Order of the Golden Fleece was gone. The French Blue Diamond has not been seen since, at least not as the French Blue.

The curse didn't stop with French royalty but continued with other prominent owners throughout history.

A Large Blue Diamond Resurfaces in London

In 1812, just as the 20-year statute of limitations regarding the theft took effect, a 45-carat blue diamond appeared in the hands of London diamond merchant Daniel Eliason. Amid widespread accusations that this diamond was actually a cut-down version of the stolen French Blue, Eliason committed suicide.

In 1820, Britain’s King George IV acquired the diamond. Following his death in 1830, his bankrupt estate sold the stone to pay off debts. Attention then shifted to London banking heir Henry Philip Hope, who some suspected had secretly bought the diamond from French thieves in the early 1800s. Hope publicly listed the stone in his 1839 gem catalog—only to die just months later.

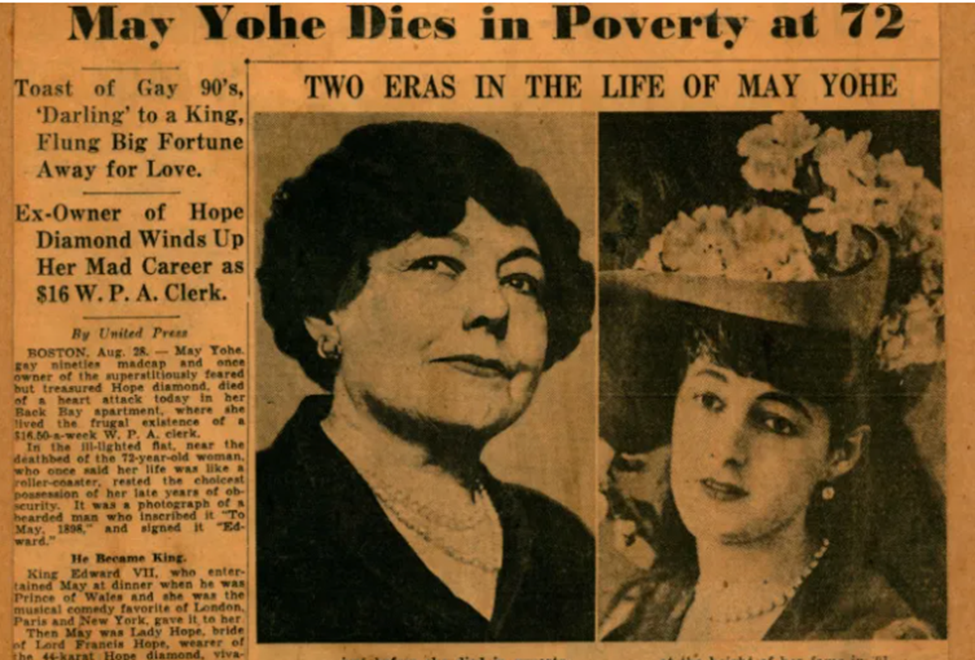

The blue diamond remained with the Hope family for the next 57 years, the last owner being the American actress, playwright, and concert-hall singer May Yohé, whose writings and stage productions often called attention to the stone’s purported curse. The diamond was sold in 1896 to settle Yohé’s pressing debts. Many believed that the celebrated singer herself fell victim to the stone’s evil power – after enduring two disastrous marriages, she died in poverty in 1938.

The Hope Diamond

The blue diamond, now known as the “Hope Diamond,” next passed through the hands of several gem merchants and jewelers, and two Ottoman sultans. Pierre Cartier, owner of the prestigious French jewelry house, purchased the gem in 1910 and took it to the U.S. to sell. He was charming, sophisticated, and skilled at selling to wealthy clients.

Cartier knew that intriguing histories helped with gem sales, and in turn, gave the purchaser an interesting tale to tell admirers at various events. Cartier thus began to fabricate a fanciful story around the Hope Diamond that included a curse, which he would pitch to potential buyers.

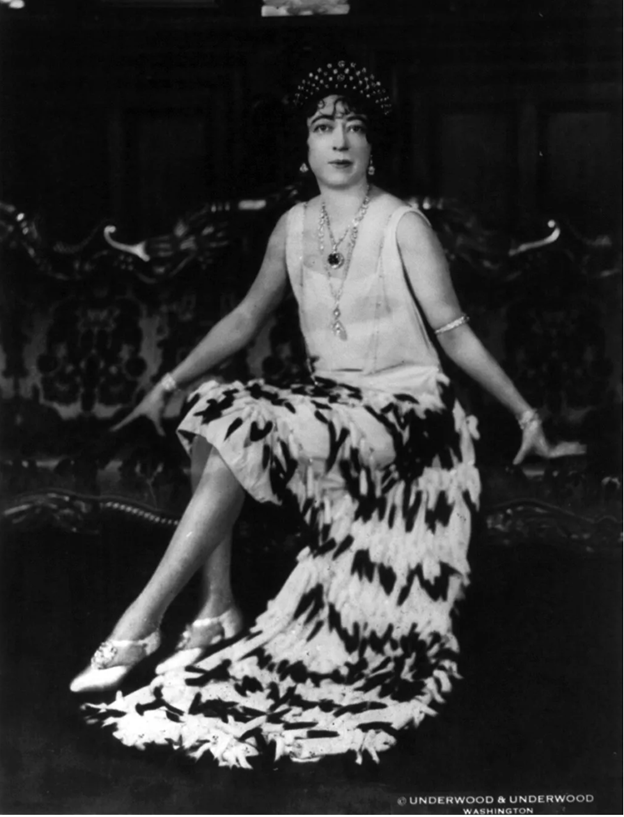

Pierre sold the gem to a wealthy American couple, Ned and Evalyn Walsh McLean, who purchased it in 1911 only after Cartier had reset the gemstone into a more contemporary setting – essentially the necklace as it appears today. The socialite and mining heiress Evalyn Walsh McLean used to boast that things that were bad luck for other people were good luck for her. Perhaps that’s why she wasn’t afraid to purchase the supposedly cursed Hope Diamond.

The Hope Diamond became Evalyn Walsh McLean’s signature in the high society of Washington, D.C. She wore it frequently, layered with her other important gems and jewelry, to events and the lavish parties she hosted.

In 2013, a Smithsonian film crew recreated the glamorous life of socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean. The one-time owner of the Hope Diamond was rumored to occasionally display the Hope Diamond on the neck of her Great Dane, Mike.

Tragedy soon befell Walsh McLean, one of the Hope’s last private owners before it was donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1958: Her 9-year-old son was struck and killed by a swerving automobile; her daughter died from an overdose of sleeping pills; and her husband, an alcoholic and heir to The Washington Post, tried to divorce her after his series of affairs and was eventually committed to an insane asylum with a declaration of insanity. The curse seemed to follow her until her death. Walsh McLean’s ghost can reportedly still be seen descending her mansion’s palatial stairway, now the Indonesian Embassy.

"Trouble to All Who Have Owned It"

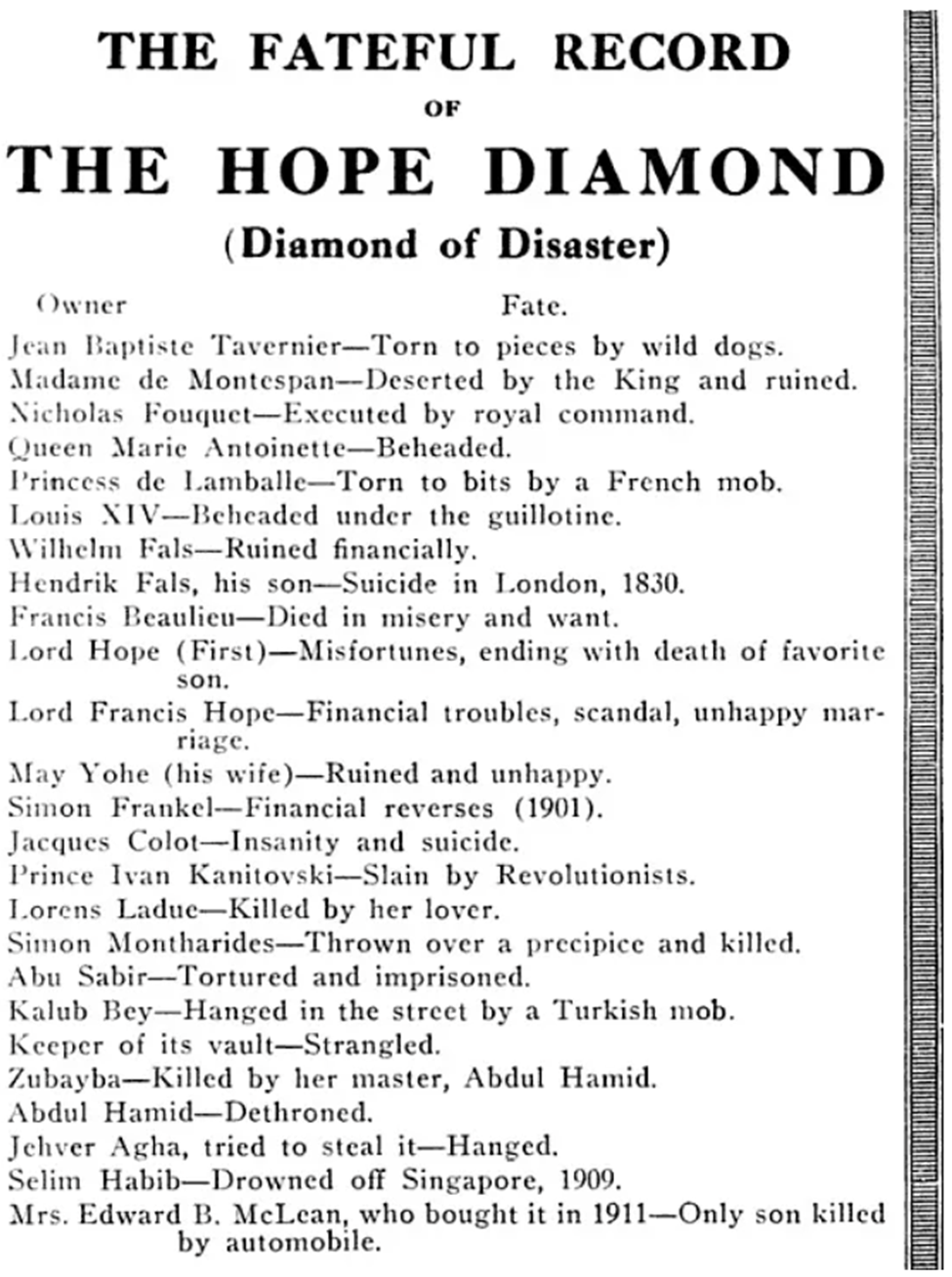

One early article about the curse appeared in the Washington Post on January 19, 1908 in the article “Remarkable Jewel a Hoodoo—Hope Diamond Has Brought Trouble to All Who Have Owned It.” The article began:

"Deep behind the double locked doors hides the Hope diamond. Snug and secure behind time lock and bolt, it rests in its cotton wool nest under many wrappings, in the great vault of the great house of Frankel. Yet not all the locks and bolts and doors ever made by man can ward off its baleful power or screen from its venom those against whom its malign force may be directed" (Washington Post 1908).

The author of the article presents a selective history of the Hope Diamond, sketching out the unlucky histories of former owners of the gem, beginning with Jean-Baptiste Tavernier and continuing through recent owners, including Lord Francis Hope and Simon Frankel, who suffered personally and financially after acquiring the Hope. Later accounts of the curse follow a similar pattern.

Several of those who contributed to the rumors of a curse could be accused of doing so for their own gain. Pierre Cartier, for example, likely embellished the stories as a sales tactic when he was trying to sell the Hope Diamond to Ned and Evalyn Walsh McLean.

May Yohé, who was once married to Lord Francis Hope, offered her own account of the curse in a book and film released in 1921. In addition to sensationalizing other accounts of misfortune, she claimed the Hope Diamond was the cause of her failed marriage and the loss of the Hope family fortune. Pieces of her elaborate tale were picked up by newspapers, helping establish the curse of the Hope Diamond as a popular modern legend.

Harry Winston, New York Jeweler

The well-known jeweler, Harry Winston, purchased the Hope Diamond and other jewelry owned by Evalyn Walsh McLean in 1949, two years after her death from pneumonia. Winston incorporated McLean's jewelry into the Court of Jewels, a traveling exhibition of gems supplemented by a jewelry fashion show.

Large and famous diamonds, including the Hope Diamond, the Star of the East Diamond, and the 127-carat Portuguese Diamond (now also part of the Smithsonian’s collection), were featured as part of the show. The exhibit traveled throughout America from 1949 to 1953 to teach the public about precious gems and raise money for civic and charitable organizations – all without bad luck! Indeed, the show brought good luck for a great many people as it traveled many thousands of miles raising money for charity.

Harry Winston once stated: “I want the public to know more about precious gems. With so much expensive junk jewelry around these days, people forget that a good diamond, ruby, or emerald, however small, is a possession to be prized for generations."

A Gift to the American People

In 1958, Harry Winston donated the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution. The idea had come to him several years before in a flash of inspiration. Winston wanted to give something back to the country that had given him, a high-school dropout of humble Ukrainian background, so very much over the years.

At the time, the Smithsonian had only a very modest gem collection and Harry's secret ambition was to make America's gemstones rival Britain's in the Tower of London. He hoped such a gift would inspire other rich Americans to donate their own magnificent jewels.

Donating the Hope also would give Harry, whose taxes had escalated along with his profits, a much-needed tax credit. His accountants applauded when he told them his plan, but for Harry, a tax break wasn't his main motivation.

Arrangements went forward, and when an Internal Revenue official phoned to question the substantial amount Harry had written off against it, he replied, "Find me another one like it to compare the price." He estimated that while he owned it, the Hope had traveled around 400,000 miles raising money for charity and had "brought him no bad luck."

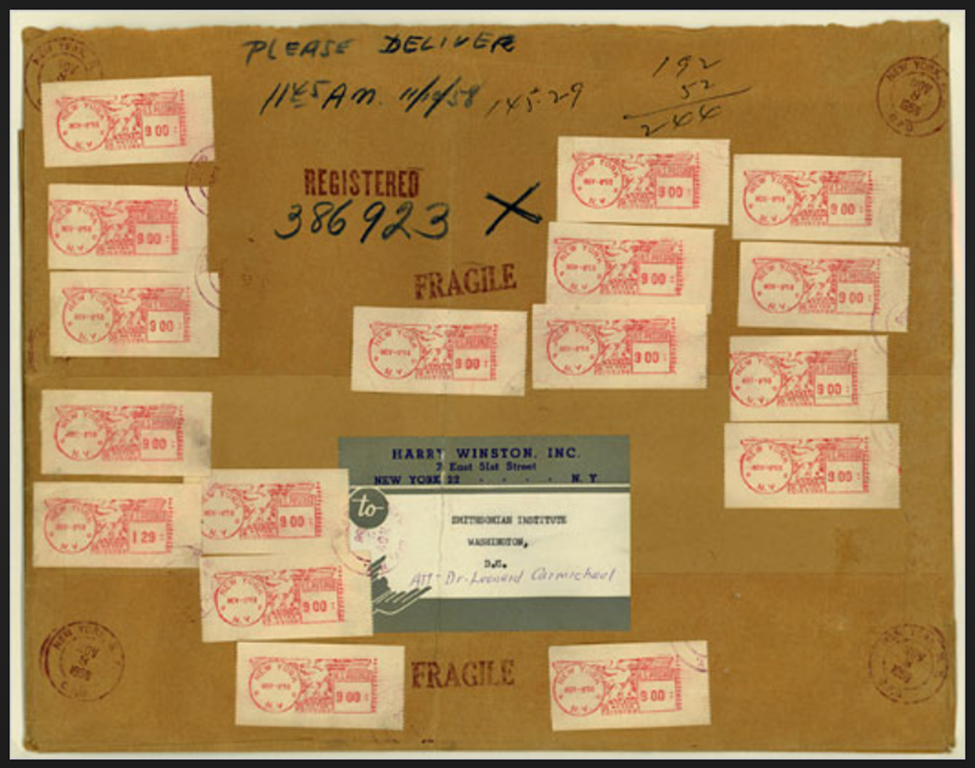

Packing the necklace for shipment was done by a former New York policeman who worked in Winston's shipping department. The necklace was placed in a rectangular black suede case, then swathed in tissue. This all went into a white cardboard box which was then wrapped in brown paper and sealed with gummed tape. Winston's label was affixed and the package addressed to "Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Attention: Dr. Leonard Carmichael, Secretary of the Smithsonian." The package weighed three pounds, thirteen ounces, but most of this was packaging, since the diamond without its companion diamonds weighed just over one-third of an ounce.

On November 10th, the Hope arrived at the Smithsonian, shipped by registered U.S. mail and insured for one million dollars.

Mrs. Harry Winston presented the Hope Diamond to Dr. Leonard Carmichael, Secretary of the Smithsonian, and Dr. George S. Switzer, Curator of Mineralogy. The Hope Diamond was exhibited in the Gem Hall at the National Museum of Natural History and almost immediately became its premier attraction. The Hope's star power was apparent – attendance at the museum just about doubled.

Curiously, the Smithsonian did not even mention the "curse" in its press release, although it mistakenly acknowledged "the legends attached to the Hope date back many hundreds of years."

Is the Curse Real?

If the curse is viewed as a supernatural causal agent that brings misfortune to owners of the stone, then no, there have been no agents or factors that can be empirically demonstrated to contribute to a curse.

Even if there were a supernatural entity (likely a Hindu deity in this case), why would it get involved in a curse manufactured by a Frenchman to sell a diamond to a rich American? The Hope Diamond is not well known in India and it was not associated with a ruler or temple.

Researchers in psychology suggest that confirmation bias plays a central role in maintaining the curse narrative. Once the concept of the curse was established, people began selectively attending to and remembering events that confirmed this belief while overlooking contradictory evidence. When owners of the diamond experienced misfortune, these incidents were immediately attributed to the curse, while periods of good fortune were typically disregarded or not documented with the same enthusiasm.

Many of the owners lived during times of significant social and political upheaval. The tragedies mentioned in this article were more common in times that had limited medical knowledge, higher infant mortality rates, and shorter life expectancies.

A rigorous statistical examination reveals that the "curse" narratives predominantly result from confirmation bias and selective historical interpretation. By applying statistical probability models to the life outcomes of the diamond's owners, we can demonstrate that the reported misfortunes are within expected ranges of human experience.

The human tendency to find patterns and assign supernatural explanations to coincidental events plays a significant role in perpetuating the curse mythology. Each tragic event becomes another thread in a carefully woven narrative of supernatural intervention.

What we do know is that embracing the "curse" narrative was obviously a good move for owners seeking to maximize their gains when the gem was sold.

As Gabriela Farfan, the curator of gems and minerals in the Museum of Natural History, explains, this is a common marketing tool in the gem industry. “Some of those owners were desperate to sell and likely decided that even bad publicity is good publicity,” she said.

When the new Harry Winston Gallery opened at the Smithsonian's Natural History Museum in 1997, curator Jeffrey Post, who retired from the Smithsonian in 2023, wrote "For the Smithsonian Institution, the Hope Diamond has obviously been a source of good luck." Thankfully, Farfan also said the museum has faced no ill fortune on account of the priceless stone.

Conclusion

The diamond's true power lies not in supernatural malevolence (i.e., a curse), but in its ability to capture our imagination, representing our collective fascination with its beauty and more than 300-year history as a treasure, heirloom, and more recently, as specimen number 217868, the catalog number it was assigned upon arrival at the Smithsonian in 1958.

Today, the Hope Diamond resides safely in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History where it continues to intrigue millions of visitors, its legendary curse transformed into a captivating historical narrative.

Principal Sources

Fowler, Marian, "Hope, Adventures of a Diamond," published by the Ballantine Publishing Group, 2002.

Kurin, Richard, "Hope Diamond, The Legendary History of a Cursed Gem," published by Smithsonian Books, 2006.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, "History of the Hope Diamond."