The Interesting Story Behind the MLK, Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC

by Ken Rock, MSDC Editor

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, no single figure consumes as much commemorative attention in the U.S. as does Martin Luther King Jr. This is reflected in the thousands of schools across the country that honor MLK Day each year, in the streets bearing his name that span across the nation’s landscape, and in the 2011 unveiling of the Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial in Washington D.C. The memorial, located on the National Mall, was officially dedicated on October 16, 2011 and stands as an impressive tribute to one of the most influential figures in American history. One of the more surprising aspects of this memorial is the material chosen for its construction – granite from China.

Selecting the Design

In 1996, Congress authorized Martin Luther King, Jr.’s fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha, to establish a Memorial to him in Washington, DC. King joined the fraternity in June 1952 while he was attending Boston University to complete his doctoral studies. The Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation held a design competition and identified the Tidal Basin site for the memorial’s location.

In 2000, after reviewing submissions from 906 entrants who joined the competition, the judges selected ROMA Design Group’s plan for a stone with Dr. King’s image emerging from a mountain. The plan’s theme referenced a line from King’s 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech: “With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.”

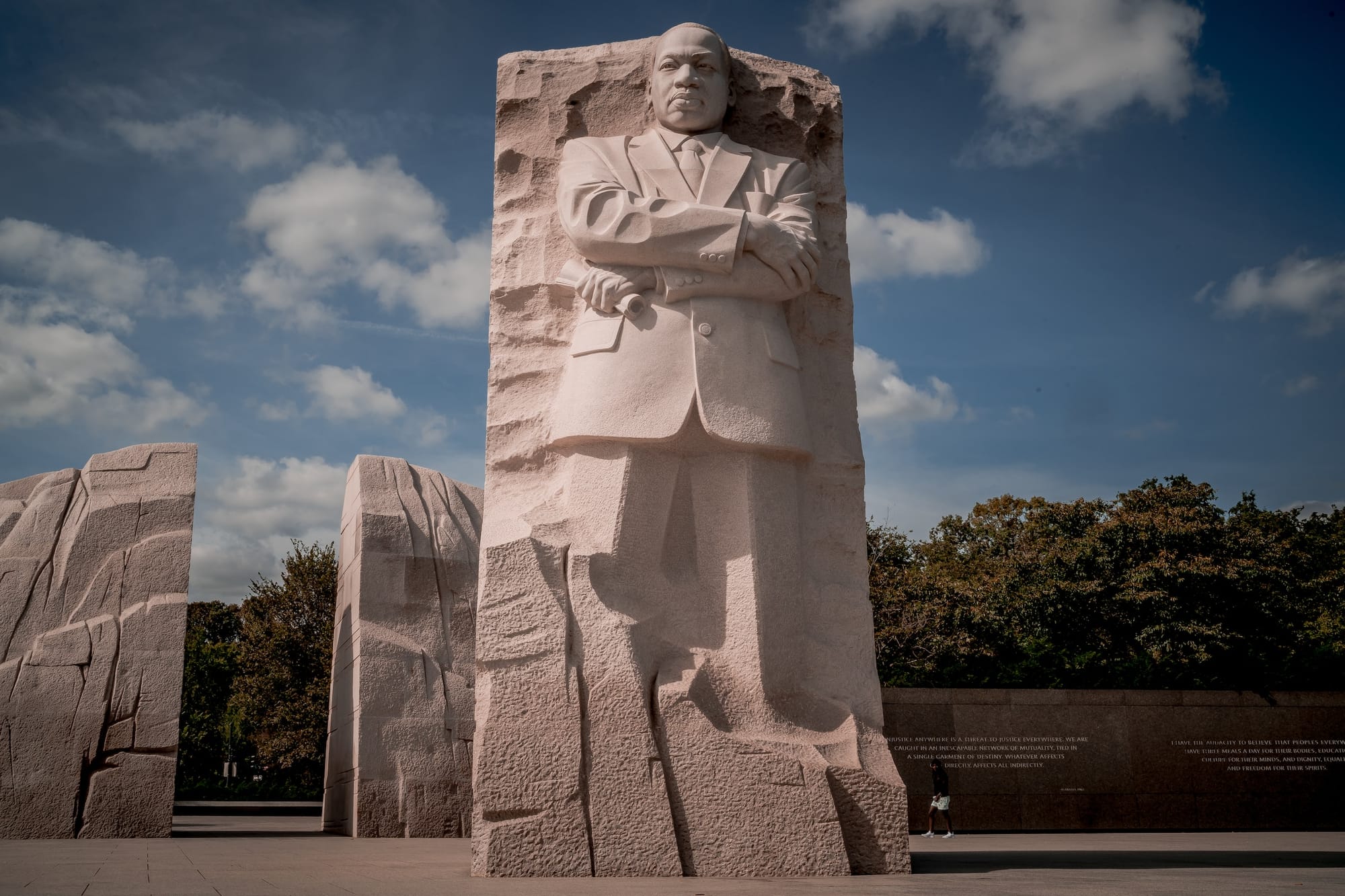

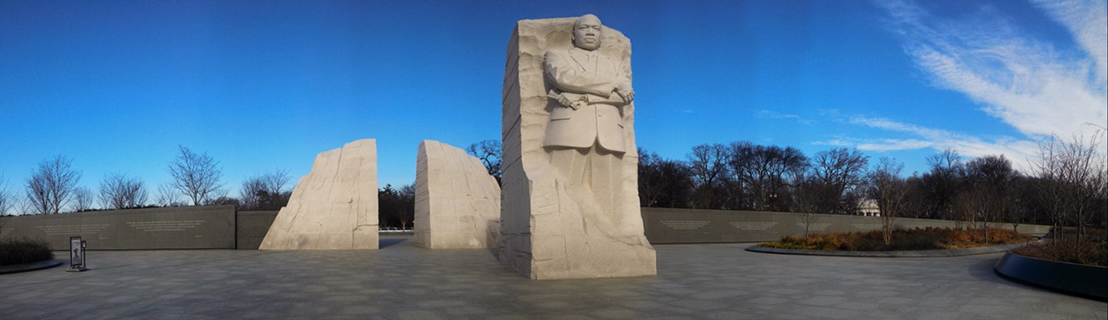

The final design includes a massive carved mountain with a slice pulled out of it, symbolizing the “Stone of Hope” being hewn from the “Mountain of Despair.” Reinforcing this motif, the edges of the Stone of Hope and the Mountain of Despair incorporate scrape marks to symbolize the struggle and movement, as well as an engraving of the words “Out of the mountain of despair, a stone of hope.” Visitors may enter the memorial through the Mountain of Despair and tour the memorial reflecting on the struggle that Dr. King faced during his life, approaching the plaza where the Stone of Hope stands. In the stone, a carving of Dr. King gazes to the horizon, thoughtful and resolute.

A 450 foot-long inscription wall includes excerpts from many of King's sermons and speeches. On this crescent-shaped granite wall, fourteen of King's quotes are inscribed, the earliest from the time of the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama, and the latest from his final sermon, delivered in 1968 at Washington, DC's National Cathedral, just four days before his assassination.

The relief of King is intended to give the impression that he is looking over the Tidal Basin toward the horizon, and that the cherry trees that adorn the site will bloom every year during the anniversary of King's death.

To bring this vision to life, the memorial's design utilizes 159 gray granite blocks weighing around 600 tons in total. These blocks were expertly carved in China and then transported to Washington, DC where they were carefully reassembled and completed to create the likeness of Dr. King.

Choosing the Sculptor

The mostly consensual process that occurred from 1996 to 2007 became much more contentious when the focus turned to the specifics of the design and production of the statue itself. The first controversy emerged around the artist chosen to sculpt the 30-foot statue, which stands 11 feet taller than the statues of Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln.

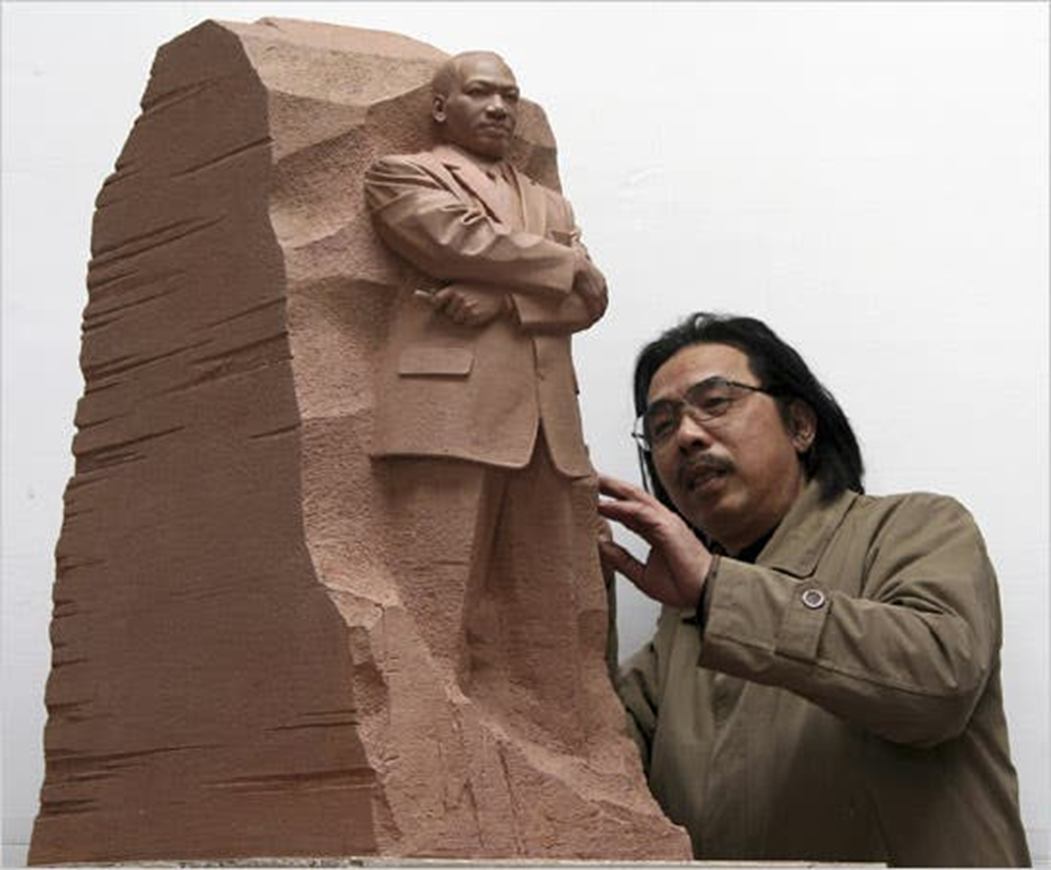

A search team, led by Ed Jackson, was formed to find a qualified sculptor. In 2006, at a stone-carving forum in St. Paul, Minnesota, the team discovered the work and person of master sculptor Lei Yixin, a Chinese national from Changsha, Hunan province, who “had carved more than 150 public statues,” including one of Mao Zedong. As Jackson put it, they had found someone of “‘exceptional talent’” who could complete such a monumental work.

Lei Yixin was one of the most prominent sculptors in China. Some of his past works are in China's National Art Gallery collection. Touted as a national treasure in China, he felt very fortunate to be chosen to work on the monument. Architects for the project sought out Lei after he was recommended by several of his peers. Before him, the foundation had conducted an extensive search in Italy, but few had Lei's experience with granite.

The choice of Lei as artist and China as the source of the materials and site for carving the statue generated strong criticism. The California Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) passed a resolution opposing the choice because, as Chapter President Gwen Moore said, “It’s an insult. This is America and, believe me, there’s enough talent in this country that we do not need to go out of the country to bring in someone to do the work.”

While a number of people voiced a preference for an African American sculptor, the most consistent line of critique took Moore’s more nationalistic tone. Washington Post columnist Marc Fisher put it directly, “the image of King is being carved out of foreign granite…. It is not jingoism but rather a healthy sense of pride and loyalty that mandates that this memorial be designed and executed by those who live in the country that King so inspired and changed…. King’s message is universal, but his story is American.” These concerns reflect contemporary American anxieties about outsourcing, the status of American exceptionalism, and the general fear of China as a rising economic and political power.

There was also a barely subtle, racialized anti-Chinese element to this critique, indicated by a persistent rumor that the Chinese government had donated $25 million to the Memorial Foundation in order to secure Lei Yixin as the sculptor and China as the site for the work and source of the stone. There is no evidence that this is true.

Despite the controversy, the Memorial Foundation did not accede to the appeals to find a new sculptor. After being selected, Lei noted that "I am familiar with Martin Luther King. I think it will be an extraordinary work. I have carved sculptures for many famous people in China. But when he [the executive architect of the project] talked about the location and showed me the drawings of the sculpture, I was overwhelmed – this is such a great and important project!"

Sourcing the Granite

Lei’s plan was to carve the statue in China out of granite. He worked closely with the Foundation, and to some extent, the King family, to choose the material — shrimp pink granite from China’s Fujian Province — and to generate the likeness reflected in the final product.

Lei Yixin describes the material, "The stone is granite, it is very hard. The color is light beige, close to skin color. …carving is very difficult, but once it is carved, it will be an artwork forever." The statue required significant technical expertise to execute such a complex and large-scale sculpture.

The executive architect for the memorial, Ed Jackson Jr., said granite of that hue and quantity was not available elsewhere. This “outsourcing,” as critics called it, spawned an angry Web site, as well as an investigation by the inspector general of the Interior Department because it was felt that using a source outside of the U.S. undermined domestic industries.

Ultimately, the decision about the source of the granite remained unchanged and the project moved forward with more controversy as the detailed design of the statue began to take shape.

A Controversial Statue

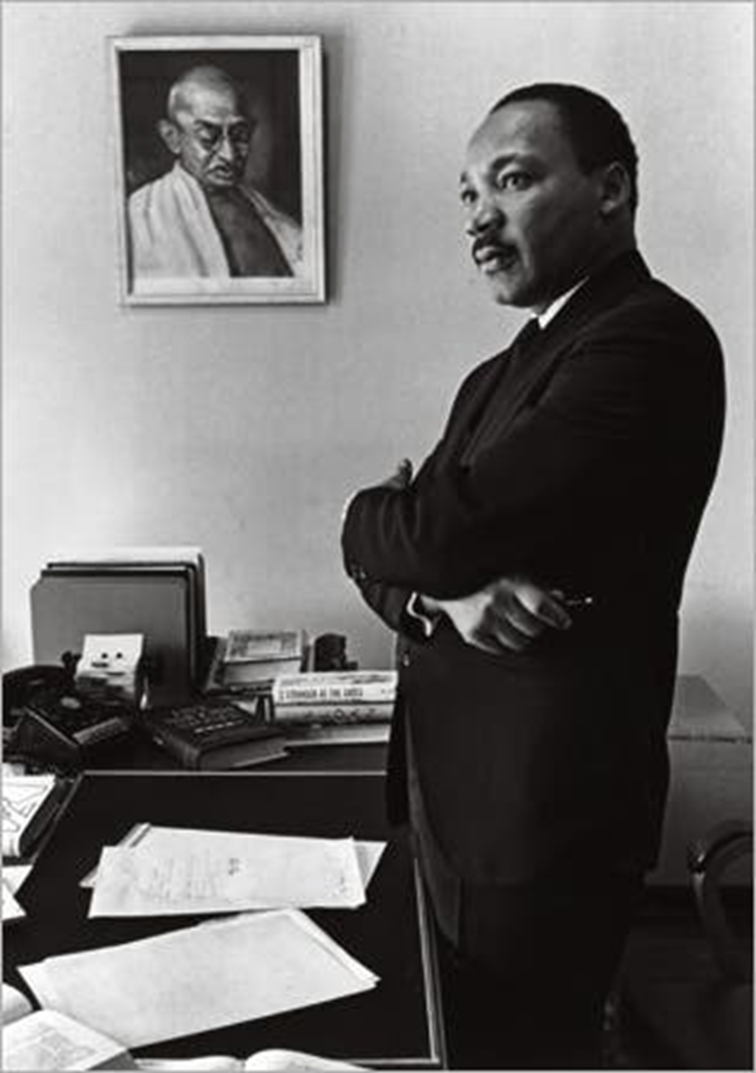

Lei Yixin filled the walls of his studio with hundreds of photographs of Dr. King and studied them until he held the essence of the man’s spirit firmly in his mind. He created a three-foot scale model of the sculpture among other sculpture models, based on the photo below, before sculpting the 30-foot final version. This initial model proved to be another source of bitter controversy for the project.

In late 2007 Lei presented his first scale model of the sculpture, which is rendered in light brown clay and shows King standing, arms crossed, his body emerging from the stone. Lei did not choose the pose. The ROMA Design Group selected it, with the approval of Foundation executives. However, in June 2008, the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), which had approved the initial design in 2006, expressed its displeasure with the image brought to life in Lei’s model and demanded changes.

According to the CFA, Lei’s representation of King “features a stiffly frontal image, static in pose, confrontational in character.” Thus, the CFA “recommended strongly that the sculpture be reworked, both in form and modeling, to return to a more sympathetic idea of the figure growing out of the stone...,” including changing King’s face so that he would have “a less furrowed brow, a softer mouth.”

These official criticisms were echoed in the public press. For example, in response to the CFA’s report Washington Post columnist Fisher expressed his outrage at Lei’s rendering of King’s image: “Nowhere but in this proposed arms-crossed sculpture is King seen in the arrogant stance of a dictator, clad in a boxy suit, with an impassive, unapproachable mien, looking more like an East Bloc Politburo member than an inspirational, transformational preacher who won a war armed with nothing but truth and words.”

In response to these criticisms, James Chaffers, a professor of architecture at the University of Michigan and one of two African American scholars who served as official artistic consultants to Lei, conceded that the “sense of confrontation in the sculpture was not a coincidence. ‘We see him as a warrior for peace … not as some pacifist, placid kind of vanilla, but really a man of great conviction and strength.’” Ed Jackson, who consulted with the “King family throughout the process, said that the bold representation was intentional.”

Jackson presented to two of King’s children, Martin Luther King III and Bernice King, four photographs of Lei’s rendering of King’s image, and he asked them which most resembled their father as they remembered him. As recounted in a USA Today interview, Jackson said that “Their response was the first one…. I informed them that this was the one that had generated all the controversy about their father looking confrontational. Martin said, ‘Well, if my father was not confrontational, given what he was facing at the time, what else could he be?’” Both sides of this debate about King’s image agreed that the model did not look warm and welcoming, but they differed on what this said about King and by extension about American race politics past and present.

The CFA saw a confrontational, stiff and stern King as a problem that needed correcting, a mistaken representation of the Civil Rights Movement leader. By contrast, Professor Chaffers, Ed Jackson, and Martin Luther King III saw and encouraged these same elements as speaking to the truth about King and his politics. Thus, in 2008, what emerged was a confrontation over the role of confrontation in the story of American race politics and race relations.

After considerable debate and despite all the criticism and demands that the image be reworked, the finished Stone of Hope sculpture is identical to Lei’s original model, except for a slightly softened facial expression. The stern, confrontational pose that had so troubled the CFA and critics in 2008 remained, and most reviews have accordingly been quite critical of the memorial and statue. The debate over the meaning of King’s image and legacy only intensified with the unveiling of the MLK Memorial and Stone of Hope monument in the summer of 2011.

Conclusion

To many visitors, the expanse of granite and the impressive carved image not only represents the enduring nature of Dr. King's legacy, but also serves as a reminder of the indomitable human spirit in the face of adversity. No one can foresee how people will read and react to the MLK Memorial in the long term. Civil rights and labor organizations have already held marches in which the MLK Memorial served as the final destination. One can only imagine what marches, speeches, and demonstrations may be held there in the future, and how the meaning of the site itself will evolve and shape new political memories and challenges.

Sources:

Kevin Bruyneel, "The King’s Body, The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial

and the Politics of Collective Memory," in History & Memory, Vol. 26, No.1. Spring/Summer 2014.

Megan Gambino, Smithsonian Magazine, "Building the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial," August 18, 2011.

National Park Service, Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, District of Columbia.