The Story Behind the New 8,000-Pound Quartz at the Smithsonian

A one-of-a-kind natural quartz now welcomes visitors to the natural history museum

by Abigail Eisenstadt, from an article published through the Natural History Museum's communications blog, Smithsonian's Voices, which is hosted by Smithsonian Magazine. Used with permission of the author.

From sandstone to gemstones, quartz is everywhere. In its natural form, it is the second most common mineral in Earth’s crust and its varieties include amethyst and citrine gems. In its synthetic form, it’s a key ingredient in watches, radios and other electronics.

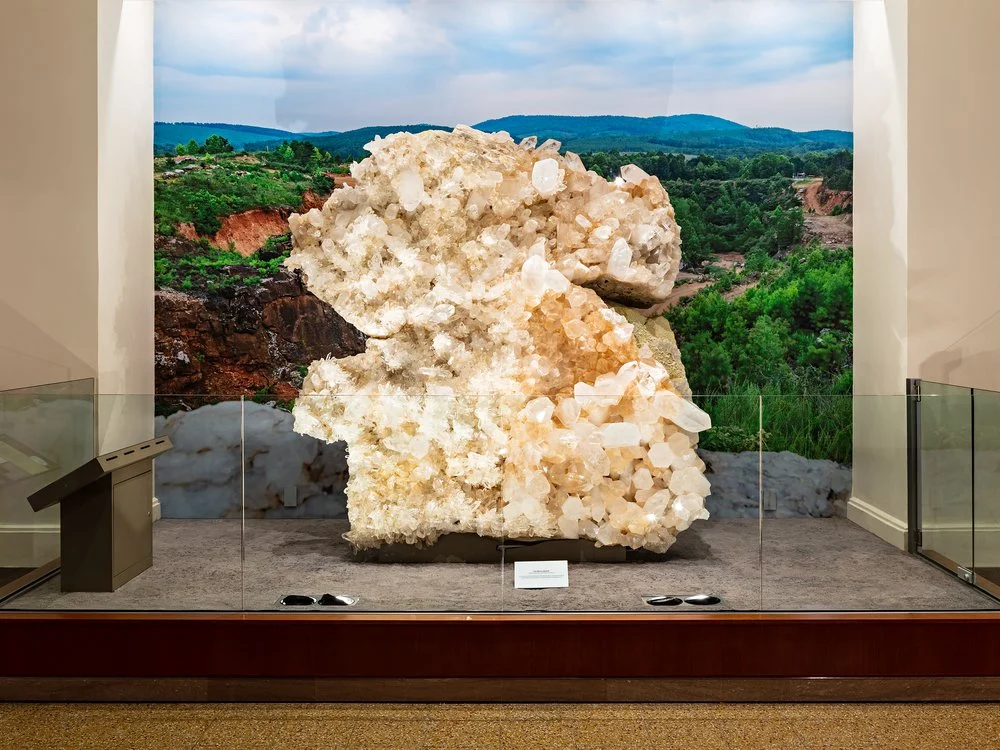

Although quartz is everywhere, an 8,000-pound slab of natural quartz is rare to come by — unless it’s the one now on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “This is the largest piece of quartz we have in our museum. It may even be one of the heaviest specimens we have,” said Jeffrey Post, mineralogist and curator-in-charge of gems and minerals at the museum.

The hefty and glittering mass of crystals, called the Berns Quartz after its donors, was originally discovered at the Coleman Mine in Arkansas in 2016. “There are very few places around the world where you get this quality of clear quartz, especially in such a large cluster. At the national museum, this is the perfect specimen to share with visitors because it’s a classic example of an American mineral,” said Gabriela Farfan, an environmental mineralogist and Coralyn W. Whitney curator of gems and minerals at the museum.

Cracking Under Pressure

In the United States, Arkansas’ Ouachita Mountains are a hotbed for quartz. They were shoved up around 300 million years ago when the South American continent crashed against its North American counterpart, buckling up layers of oceanic sandstone. “The overlying pressure from the resulting mountain of rocks squeezed hot silicon-rich water from the buried sandstone into deep cracks that were two miles beneath the surface,” said Post. “Quartz crystals grew in these fractures.”

Quartz crystals look like hexagonal prisms that culminate in a point. Their shape comes from how their atomic building blocks, silicon and oxygen, lock into precise, repeating arrangements. “Understanding the temperature, chemistry, and pressure conditions that it takes to grow these quartz crystals can help inform us about the geological context of a region at the time of crystal formation, and vice versa,” said Farfan.

The events making the Ouachita Mountains stopped roughly 200 million years ago. Afterwards, the mountains began to erode, exposing once deeply buried veins of Arkansas crystals, like the Berns Quartz.

A Natural History Icon

Post and Farfan first encountered the quartz in 2020, recognizing its value both as a specimen in the museum’s National Gem and Minerals Collection and as an object to interest museumgoers in the wonder of the natural world. “We thought it would be special to have such an iconic quartz at the front of the museum. We’ve also known the miners for a number of years, and they said they’d love the quartz to be at Smithsonian,” said Post. “But we knew if we were to acquire it, it would have to be with the help of donors. We were lucky to have Michael and Tricia Berns step in.”

Now, at last, the Berns Quartz is on display inside the museum’s Constitution Avenue entrance. Visitors who stop by can learn more about the mine where it was found and watch an educational video about the quartz’s geologic history. “What could be a more appropriate thing to see when you first walk into the museum than this major mineral specimen that represents one of the basic building blocks of our Earth,” said Post. “We hope the quartz will inspire a sense of awe in people and excite them to learn more about the world that we all live on.”

Abigail Eisenstadt is a Communications Assistant at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History. She brings science to the public via the museum's Office of Communications and Public Affairs, where she tracks media coverage, coordinates filming activities and writes for the museum's blog, Smithsonian Voices. Abigail received her master's in science journalism from Boston University. In her free time, she is either outdoors or in the kitchen.