The Mexican Mountain Town Feeding the International Crystal Market

In Piedra Parada, Amethysts are Everywhere

by Dylan Taylor-Lehman in Atlas Obscura, May 18, 2021. Used with permission of the author

PIEDRA PARADA IS A SOMEWHAT obscure mountain town in the Mexican state of Veracruz that has carved out its own special corner of an international market. The region is known for its amethysts, a type of quartz crystal with color ranging from light to deep shades of purple, formed in sometimes impressive geometric shapes. The men of Piedra Parada (“Standing Rock”) have mined these crystals for the past 70 years for buyers all over the world who covet them for both their beauty and purported metaphysical qualities. The stones from the town’s numerous mines and small excavations can be found at gem shows and in New Age stores around the world.

“Veracruz amethyst is very distinctive, the way the crystals form—you really can’t mistake it from being from any other place,” says Terry “Skip” Szenics, a longtime collector and dealer, and a fixture on the gem show circuit. “It’s special in a way that when you see a specimen and ask where it’s from, I say, ‘Are you kidding me? Of course it’s from Veracruz.’”

Piedra Parada, population 468, is about an hour drive northwest of Xalapa, Veracruz’s capital city, high in the Sierra Madres. The route takes you through the countryside and small towns, and then onto steep, winding mountain roads that switch from paved to dirt and back again and shoot rocks noisily into the undercarriage of vehicles.

The view grows increasingly spectacular with the elevation, and is truly astonishing at Piedra Parada—a wide-angle view of the horizon, overlooking farms, grazing animals, and homes with smoke curling out of chimneys.

“You can see for probably 10,000 kilometers,” says Jose Trujillo Hernandez, a crystal miner and lifelong resident of Piedra Parada, as he stands on a hill on his property at the edge of town. Hernandez sweeps his arm out in front of him as he explains that most of the mines are in an arc across the north side of the mountain. He is uncertain how many are in the area, as mines close and open as needed.

Hernandez and his brother Juan Abram share the property, which extends up and down a steep hillside and eventually back up a distant hill, with their families. The brothers, who are in their early 40s, are two of 16 children, most of whom still live nearby. There is no mining corporation dominating the area—all of the work here is done by locals to earn a living or augment their other vocations. Like most men in town, the brothers are miners and crystal vendors but also do construction, raise animals and crops, and work on local infrastructure upkeep. And like other homes in the area, theirs have tables laid out with tablecloths and crystals of different shapes, sizes, and shades for any visitor who passes through, as well as crates already packed up for wholesale.

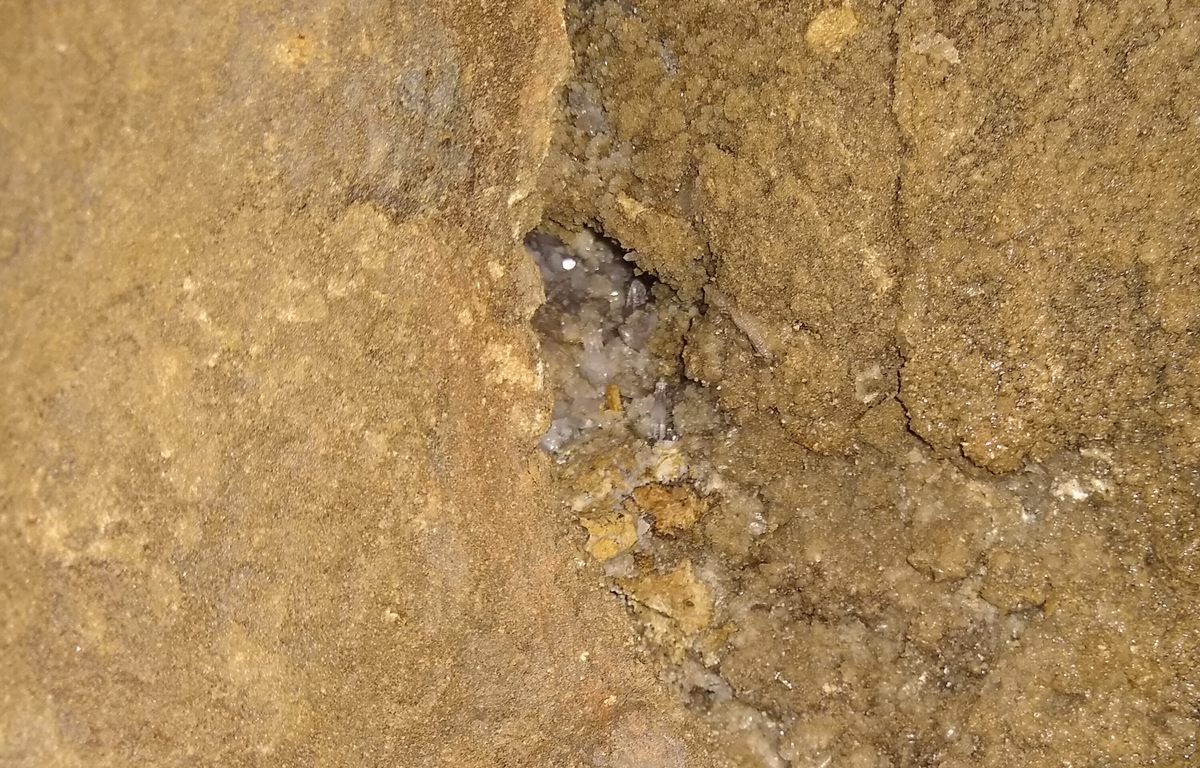

Amethysts from the Veracruz region are “classics in the marketplace because of their aesthetics. They are highly lustrous, have a wide range of color, often have a lot of the matrix rock, and have microcrystal epidote [a greenish mineral that grows alongside the amethyst],” says Steve Behling, a broker with Collector’s Edge Minerals Inc. The purple coloration is due to irradiation and the presence of iron and other elements as the crystal formed, with many crystals growing together in sprouting or artichoke formations. (More specifically, “These crystals are formed in vesicular andesite, volcanic vugs [cavities] with amethyst quartz, calcite, epidote, and various zeolites,” according to another dealer.)

“People say they’re not flowers because they grow from stone, but they are,” Hernandez says.

Amethysts are said to have mild curative properties; in fact, the name comes from the Byzantine Greek amethystos, or “non-intoxicant,” referencing a belief that drinking wine from an amethyst vessel won’t get you drunk. The water that pools in the small chasms where crystals form is likewise thought to be beneficial. Hernandez credits this water with helping cure his asthma. They’re also said to have pronounced metaphysical benefits, from opening chakras to curbing temptation.

A looming cathedral stands in the center of Piedra Parada, overlooking the road that to the hills with the mines. Scooters and dirt bikes come and go, past people and farm animals, with each bike typically carrying two or three miners and a day’s supplies.

Some of the mines are hard to spot, up hills and behind outcrops or trees. Others are completely obvious, with disgorged rocks and dirt scattered in front of what looks like a wound in the hill. Some mines have small, makeshift shelters out front, and each active mine has an altar at the entrance, adorned with candles and small offerings for the safety of the miners and in exchange for the crystals being taken from within. Long stretches of flexible plastic tubing line active mines to help circulate air in the deeper chasms.

The mining crews are generally made up of around seven people, explains Uri Juan Landa, who grew up mining on his family’s land nearby and farther south, and has worked as a dealer for 20 years. Some of the land is an ejido, or held by the community on which anyone can work, while other mines are privately owned. Each member of a mining crew kicks in some money for supplies and food, and the group splits the proceeds from the eventual sale of the crystals minus a cut—usually around 10 percent—to the private owner, if there is one.

Work goes on in the mines every day except Sunday, and generally from morning until night, Landa says, sometimes until the wee hours of the morning if it is a particularly bountiful mine. But success isn’t guaranteed; sometimes a crew can work for weeks with little to show for their efforts, he says. The area is so shot through with crystals that simply peeling flakes of rock can reveal small deposits, but these aren’t necessarily good for the market, as they are too small or too lightly colored or just plain old quartz.

Landa’s father worked in mines for 30 years using only hand tools and a headlamp. It was only in his last year of mining that he finally got a generator that allowed him to rig up better lighting. Most miners today use power tools and explosives, and some of the caves still smell like smoke and sulfur, indicating a new channel had been started or another extended farther into the cave.

Each town has the stories of men injured in the mines, including a young man who was blinded by an explosion in a cave near Piedra Parada. The risk is accepted as part of the job. “It’s always exciting to find minerals but you’re always worried about collapse. Hopefully I would just get crushed [instead of trapped],” Landa says with a grim laugh.

People take these risks because proceeds can be healthy. Many of the local vendors and miners maintain their own good relationships with dealers abroad. The crystals are usually sold abroad in lots, carefully packed into crates and shipped using a freight carrier such as DHL. Though international crystal brokers can be unscrupulous, falling off the face of the earth when payments come due, Facebook Marketplace and eBay are places the miners sometimes sell directly to the public, as is the bustling, steep, narrow one-street Callejon del Diamante market in Xalapa.

One issue with Veracruz amethyst, from a sale and dealer’s perspective, is the quantity of material on the market. It tends to stay on store shelves for a while, and doesn’t carry the rarity or mystery of something like a musgravite. Almost every mineral dealer has some Veracruz amethyst in stock, Szenics says, but most collectors already have a spectacular specimen in their collection.

Nevertheless, its popularity is enduring. Visitors from far-flung locales sometimes make the trip to Piedra Parada to get crystals directly from the source, Hernandez says, among them an eccentric millionaire from Romania who arrived in his own plane to go crystal-hunting. Hernandez hopes that improvements to local infrastructure can bring more people to them directly.

The miners’ kids have their own stashes of crystals at the ready for when people pass through. One boy fished some out of his pocket, another had his specimens stashed in a small box.

An older cousin was helping his younger counterpart learn the trade.

“Charge them 50 [pesos],” he whispered.

“200,” his cousin said. Everyone laughed. He was shaping up to be a good salesman.

This precocious salesmanship will eventually be a contribution to the well-being of their families, Piedra Parada, and the region. The mines belong to the town and the people, and over the years they’ve been able to strike a balance between using the resources to help to provide for their needs and maintaining the abundance of the surroundings.

As night set in, men could be seen coming back from the mines, greeting neighbors as they passed by or stopping to chat with their friends. It was another day in this tiny world atop a mountain, a mix of challenges and community.

“Money comes and goes, but you can’t take it into the next life,” Hernandez says. “It helps a bit, but we’ve got food, we’ve got family, life is good.”