Musings of a Mineral Museum Curator, presentation by Dr. Jeffery Post

Report by Andy Thompson, MSDC Secretary

This report is provided to encourage readers to visit MSDC’s YouTube channel to view the video of Jeff’s presentation in its entirety including the follow-up question and answer session. It runs for ~90 minutes.

Dr. Jeffery Post’s Final Presentation to MSDC as Curator-in-Charge of Gems and Minerals

Since 1984, our nation’s gem and mineral collection at the Smithsonian and the world-wide mineral community have benefited from the mineralogical research and curatorial expertise of Dr. Jeffery Post. He is now transitioning into retirement but will continue to have an emeritus role with the Smithsonian.

When Jeff, as he prefers to be called, completed his Ph.D. at Arizona State University, he accepted a post-doc research fellowship at Harvard University. Subsequently he came to the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) and began his 39 years of service.

Throughout those nearly four decades, Jeff continued to develop expertise in the diverse areas of the interface of minerals with the environment; manganese oxide minerals; single crystal and powder X-ray diffraction; electron microscopy; clay minerals; computer modeling of mineral structures; Rietveld analysis; and gemology.

Since 2007, he has coauthored at least 70 articles in refereed scientific journals which suggests his contributions in the above areas of interest have been extensive. As Cindy Schmidtlein indicated in introducing Jeff, his extraordinary service has been recognized by awards such as those from the Carnegie Foundation and Clay Mineral Society. He currently serves as President of the Mineralogical Society of America.

By his many public presentations, he has also served as a conduit between the national and international research communities, the museum-going public and mineral clubs across the U.S. Our own MSDC club has particularly benefitted. Our 81-year Mineralogical Society (MSDC) began meeting in the NMNH in January of 1942. For the past four of those eight decades, Jeff has been a supportive presence not only with use, but with other mineral clubs as well as geological societies, as well.

Jeff began his April 5th presentation to MSDC saying that the fun part of transitioning into retirement is it gives you the opportunity to think about things more broadly. What you realize is that more than the things you’ve done, you remember the people you’ve done them with. With this emphasis on relationships, part of Jeff’s talk, he said, would be on sharing some of the reasons he found his time with the Smithsonian to be so special.

Jeff chose to name his presentation “Musings” to avoid the potentially exalted language of “Wisdom” so often asked of those retiring from a lengthy career. He warned his musings should not be confused with wisdom. Rather, he likened his presentation about his favorite experiences at the Smithsonian as a bit like the top-ten lists of late-night comedian David Letterman.

Smithsonian Researchers’ Enthusiasm Was a Key Factor for Jeff

The first “favorite” Jeff recounted was a discovery he made during his post-doc research at Harvard. Hunting for a mineral research position, he applied to many universities and included the Smithsonian (SI). During his interviews, he spoke with many members of the Department of Mineral Sciences and was surprised to learn about the extensive amount of research that the SI scientists conducted. He commented, “more than anything, I was amazed that everybody I talked to (at the SI) loved their jobs.”

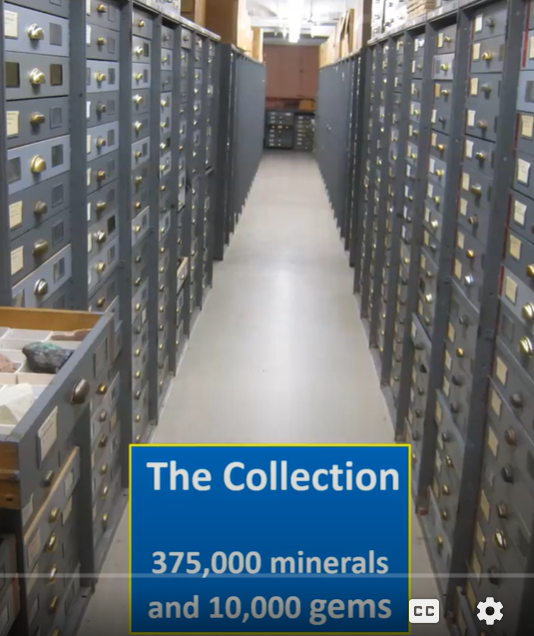

Also, the extraordinary collection of 375,000 minerals and 10,000 gems was right there to be studied. That was very different from every other place that Jeff was considering working.

So, when he was offered the mineral research position in 1984, the SI’s researchers’ enthusiasm for their work was “a key factor” in Jeff’s accepting the offer. He noted that “in retrospect, it was one of the best decisions I ever made.”

Jeff’s subsequent selection as curator of the collection in 1991 made clear that it required his becoming the interface between the world’s mineral researchers and the SI’s mineral collection which it loans to scientists throughout the world. In the end, he noted, the collection outlives all of us and is used today to address new questions such as the environment, sustainability, biomineralogy, and how life began on earth. These questions were not being worked on 32 years ago when he first took that curator’s position. So, the questions, he said, are always going to change over time. But the mineral collection will continue to be there, “needing to be interrogated,” to help resolve the new issues. “And this is the reason why the collection must continue to grow and be available to future researchers.”

Another of Jeff’s Favorites: Vast Improvements in Scientific Instrumentation

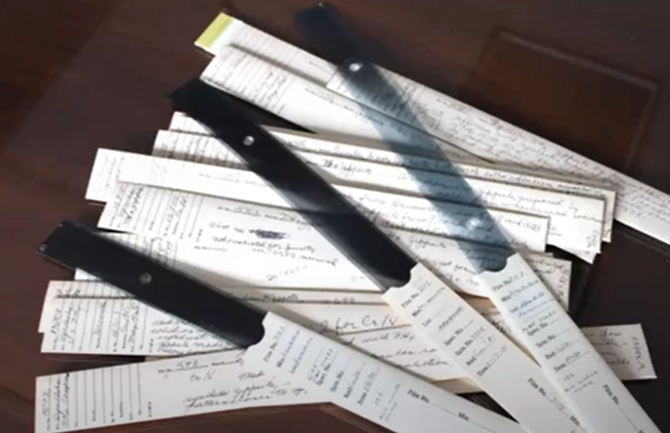

The Smithsonian has continually updated its equipment which has totally changed the way scientists have conducted their research. Jeff explained the process he had available as a grad student in the late 1970s to use X-ray diffraction patterns to identify minerals. Back then it required many hours, taking photos with long exposure times, processing the film strip in a darkroom, and matching the pattern of the line of curves against the line patterns in a book of the patterns of known elements and minerals.

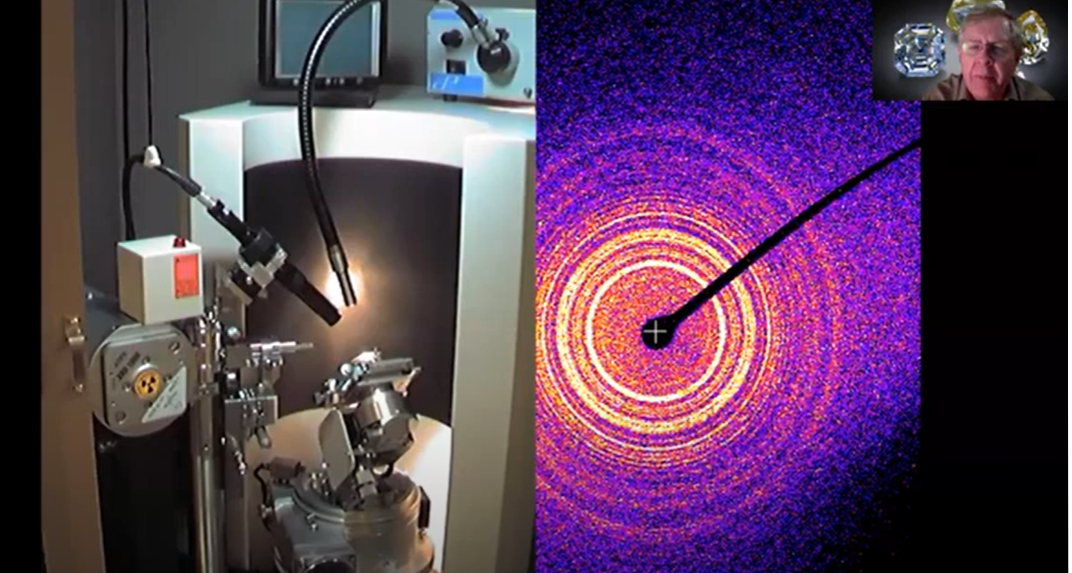

Today, researchers use an X-ray refractometer to identify the mineral bombarded by X-rays. It takes about five minutes rather than the earlier 24-hour method. Today, Jeff explained, the mineral sample or gemstone is placed on a mount, the shutter is opened for a brief exposure by X-rays, and as shown by the colorful image below, the plate captures the diffraction pattern which is then compared with a computerized data base of the images of previously identified minerals.

Going forward, Jeff said he sees even greater discoveries being made by using X-ray diffraction patterns in combination with cyclotrons. This works by sending magnetically driven, high-speed electrons through large circular pathways and crashing them into a mineral to give off X-ray patterns which can then identify the mineral under study. Even better, Jeff explained, researchers can set a fluid chemical process in motion in which crystals are formed or deformed. Its successive X-ray patterns emerging during the experiment are a bit like a movie, telling the researchers what is going on chemically during the process. This process has never-before been available and will lead to further discoveries.

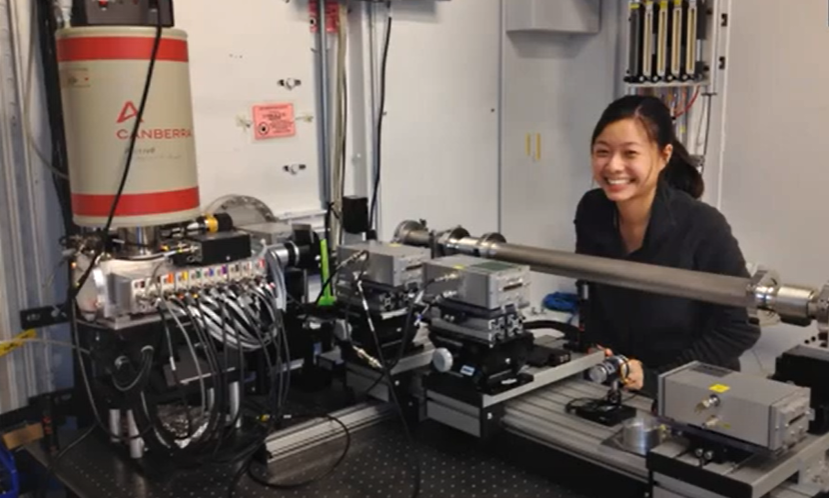

The SI does not have a cyclotron, but as shown below, Jeff and his colleagues have worked with other scientific institutions, professors, and graduate students to conduct research collaboratively.

The fact that new questions are continually emerging and that advanced technology is providing unforeseen explanations underscores the fact that the Smithsonian’s mineral collection will continue to be an invaluable legacy for addressing the issues facing future generations.

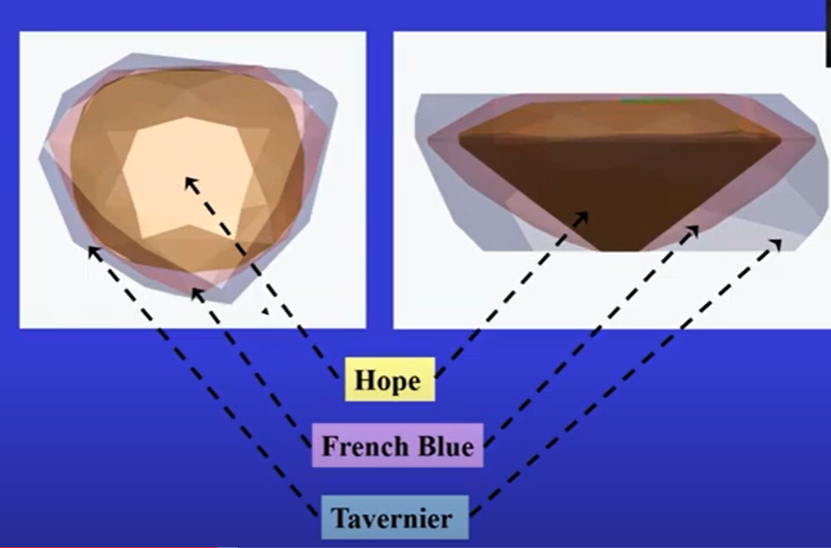

Favorite Research Findings for the Hope Diamond

Another “favorite” aspect for Jeff has been his responsibility for taking care of the Hope Diamond, shown below, which was donated to the SI by Harry Winston in 1958. As the centerpiece for the gem collection of the mineral gallery at the SI’s Natural History Museum, the world famous and very rare large (45-carat) blue diamond has drawn millions of visitors. But it also came with some unanswered questions about its earlier history. By using the above technology and additional scientific research, Jeff and his colleagues have learned a lot about the history and shaping of this gemstone.

Readers of this report will be rewarded by going to the YouTube video of Jeff’s entire presentation and listening to his recounting some of the intriguing stories that research has brought to light about this national treasure. Click on the link above (also the end of this program report) and you will hear the full story and also learn the answers to the following questions.

Another Favorite: The First Ever Comparison of Hope and Wittelsbach Blue Diamonds

“Just me, the Wittelsbach, and the Hope Diamond within the Smithsonian’s vault -- the two most famous blue diamonds in existence,” seen side by side for the first time in history. Never-before had anyone viewed them together. Both gems came out of India only a few years apart. But could they once have been part of a larger stone that was cut and separately sold off?

Jeff recounted how he invited SI researchers and others from the GIA to spend the night comparing the phosphorescence and measuring the birefringence, the structural strains of each of the two crystals’ structures. Viewing both diamonds under crossed polarized light helped to unlock the possible origins of these historic diamonds.

This collaboration in 2010 was made possible because Mr. Laurence Graff, who then owned the Wittelsbach, made it available to the Smithsonian for research. He also enabled the public to see these two world-famous blue diamonds on display together, side by side, at the Smithsonian from January to August of that year. Go to the YouTube video link below and learn about this once-in-a-life-time experience and what the SI researchers concluded about the relationship between these two diamonds.

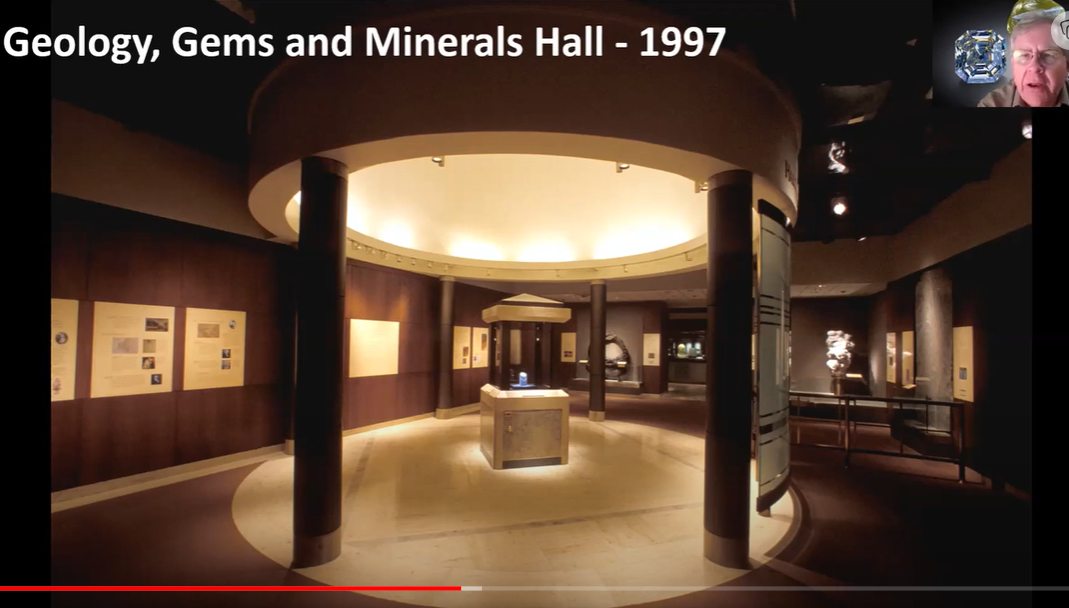

Renewal of the “New” Geology, Gems and Mineral Hall

“Renewal of the Geology, Gems and Minerals Hall was one of the greatest experiences of my career,” said Jeff. This was largely because of all the highly talented persons who pulled together: the designers, writers, colleagues, and content people, as well as the funders who made it all possible.

Discussions about a renewal started in the early 1990s and it took until 1997 to make it all happen.

“After all that work, when you see it open, it is an indescribable feeling.” In the past 25 years, many millions of people have visited the exhibit and learned about minerals and the earth. So, Jeff said, it has been a privilege to have helped make that happen.

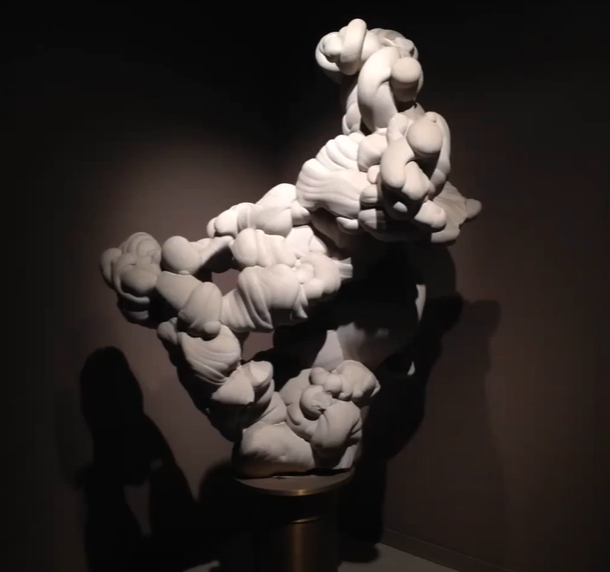

One of Jeff’s favorite minerals in the Hope Diamond gallery is the above sandstone concretion. When he visits the exhibit and sees members of the public standing and staring at it, Jeff comments to them that this is a natural object and is the way it actually came out of the ground. He says their common reaction is to look at him as though he were nuts. “This is one of the things that amazes people and still amazes me,” he commented.

In another room, the gems gallery, the exhibit features the great quartz crystal ball which has been continuously on exhibit since 1925. It, and almost all the gems in that display, have been donations, each of which has a compelling mineral story as well as stories about the persons who collected and donated the minerals. “That is what makes this room so interesting.” Some of those stories, Jeff noted, are contained in the book Cindy mentioned in her introduction, The Smithsonian National Gem Collection ― Unearthed: Surprising Stories Behind the Jewels, (2021) authored by Jeff.

Museum Visitors Say They Most Appreciate the Gem & Mineral Collection

The SI’s National Museum of Natural History regularly surveys its visitors and asks what they most remember about their visit. Jeff said the mineral exhibit almost always comes out at the very top. People come to the museum kind of knowing what gems and dinosaurs look like. But when people see the unpolished minerals and it sinks in that this is how they were formed in nature, they are astounded. It opens a whole new level of awe and excitement about the earth and about science.

Special Exhibits Have Been Among His Favorites

In the year 2000 and only for a short time, the Smithsonian exhibited, for the only time in history, the colorful Dresden Green Diamond and the Hope Blue Diamond. They will probably never again be together, Jeff noted.

The story of whose dream this exhibit fulfilled and how it came about might well entice readers to turn to the YouTube video to learn this fascinating story.

Later, “The Splendor of Diamonds” was another hugely successful exhibit and brought together a dazzling display of diverse colored diamonds not including the Dresden Green. “The Allure of Pearls” was another gathering of the world’s most beautiful pearl specimens, which, like the diamonds exhibit, were subsequently dispersed back to their owners, and very probably will never again be gathered together in a single display.

Seeing the Smithsonian Mineral Collection Built with Gifts

Another favorite experience for Jeff has been working up close and personally with the generous supporters. Jeff said, time after time they told him in so many words: this extraordinary mineral deserves to be on display for all the people to see and enjoy, free of charge. Again, “it’s the people you worked with that you remember.”

One of Jeff’s greatest joys has been intersecting with diverse people, including extraordinary donors, who have a vision and commitment to sharing the earth’s treasures so all people can experience these marvels.

One example is the “Smithsonian Gem and Mineral Collector Group,” which funded the purchase of the “Cranberry Crown” elbaite shown below. Each year the SI Department of Mineral Sciences selects an array of desirable specimens which they show to this group for possible purchase. The donors provide the funds and then vote on which mineral to purchase as a gift for the national collection.

One of the world’s most beautiful rubies shown below is another example of a generous donor supporting the nation’s need to build its mineral collection and train scientists. Jeff recounted the story of how Peter Buck, a professor at a small college in Connecticut, helped a student in financial need by together starting a sandwich shop. This grew into the Subway restaurant chain.

Peter donated the ruby shown above which is named in memory of his wife. Peter took a very strong interest in the National Museum of Natural History. He has generously supported the mission and many endeavors of the SI Department of Mineral Sciences.

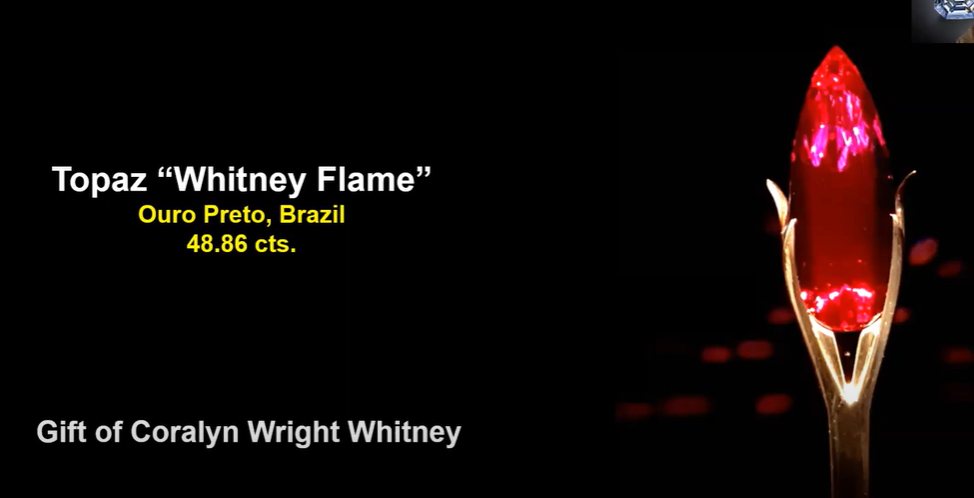

Another extraordinary donor has been Coralyn Wright Whitney, a former professor at Washington University with an incredible passion for gems and minerals. At the annual Tucson show one year she approached Jeff and asked: “What can I do to help you build the collection?” She ended up buying a number of extraordinary pieces for the collection and providing an endowment to support many of the activities of the Department.

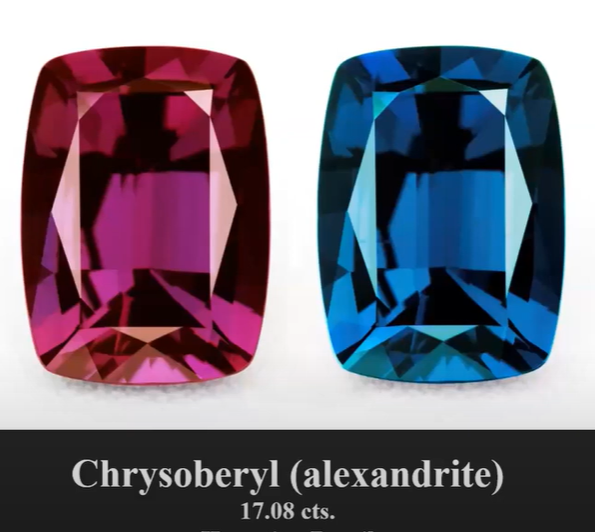

Among the first gems she funded was one of the largest chrysoberyl (alexandrite) gemstones in the world, 17.08 carats, from Brazil, here shown below under two different lighting conditions.

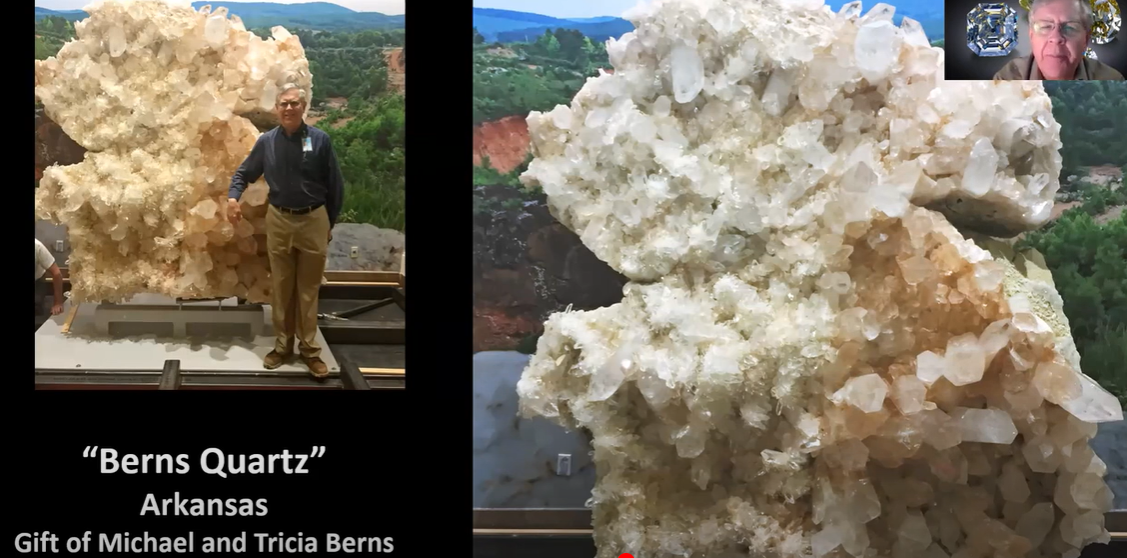

She and others, too numerous to identify here in this report, also donated the following gems.

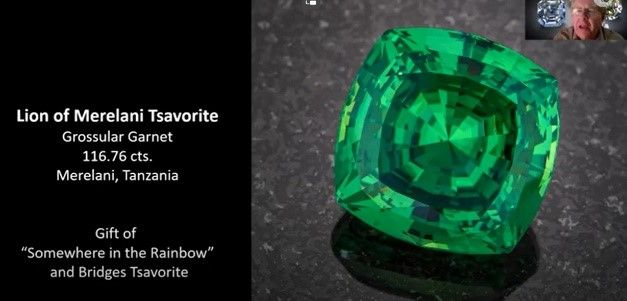

Another world class mineral that went on display at the NMNH beginning in April 2023 is the 116-carat Lion of Merelani Tsavorite. It was donated in memory of slain geologist, Campbell Bridges, who had a long relationship with the Smithsonian. This gemstone is the subject of a separate article in this newsletter.

Shown below is a millerite from Antwerp, New York. When Jeff’s high school visited the SI’s NMNH on its field trip, he said this mineral stuck in his mind. Of course, today, it continues to be on display.

Jeff said: “This (millerite) reminds us of the effect minerals have on the public, the sense of awe they create.”

After having visited our exhibits, “this sense of awe sends people home changed, thinking about the earth in new ways. They have been transformed. Standing before these minerals they say: Oh my gosh, these things came out of the earth like this. What an amazing place this (Earth) is. The minerals do an incredible job connecting people with science, making life a little more interesting.”

Jeff then transitioned his April 5th talk to a theme which he has been sharing annually with mineral clubs, namely what he and his SI colleagues have discovered and, with donors’ help, acquired for the Museum from the staff’s annual trip to the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show.

An Important Question: Who will be carrying on after Jeff retires?

Jeff said that he feels good about leaving at this time because on staff there is an incredibly talented and competent team of mineralogists and researchers.

What did they bring back from Tucson?

Before Tucson 2023, the largest Peridot crystal from the Aheim, Norway site in the NMNH collection was the small 4-carat deep green crystal shown above. But more recent excavations of the Aheim mine’s dump unearthed the 51.2 ct rough which the SI team was able to purchase due to the generosity of GLMSMC, one of MSDC’s sister clubs, to fill this gap in the Smithsonian’s collection.

The team brought back many other extraordinary minerals which fill in some of the gaps in the national collection. They include:

· a never-before-seen cats’-eye blue topaz, 135.8 ct, and

· an unusual 9-inch-wide cluster of quartz crystals from Inner Mongolia, China.

“All kinds of weird things coming out of that part of China,” Jeff noted.

The team also obtained a beautiful purple colored 2-inch long Strengite (iron phosphate) from Keveaniemi Mine, Kiruna, Sweden and additional rare minerals from Madagascar, Russia and Afghanistan, and quartz crystals with petroleum inclusions from Madagascar.

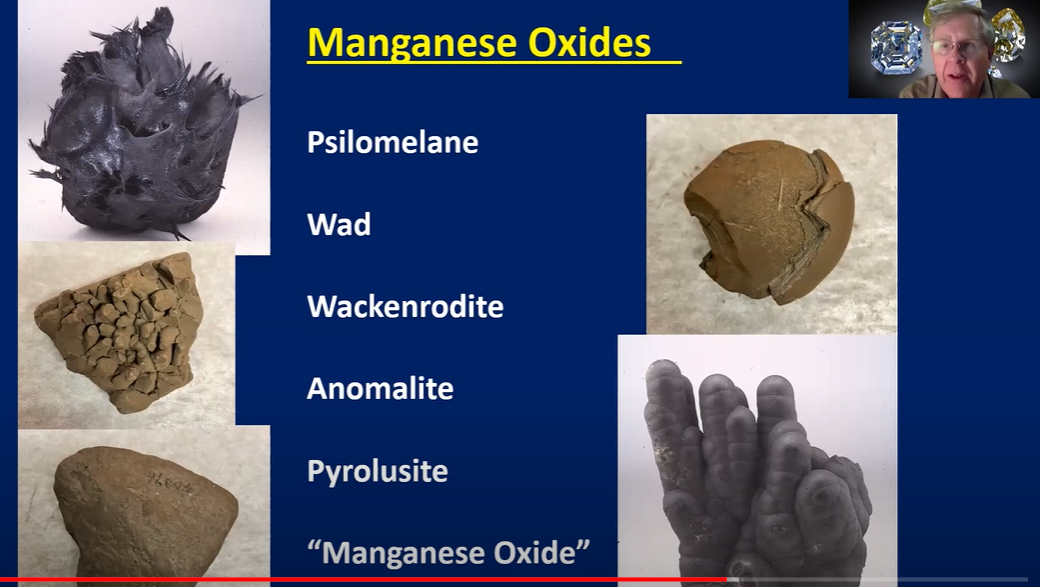

One of Jeff’s Favorite Research Subjects: Manganese Oxides

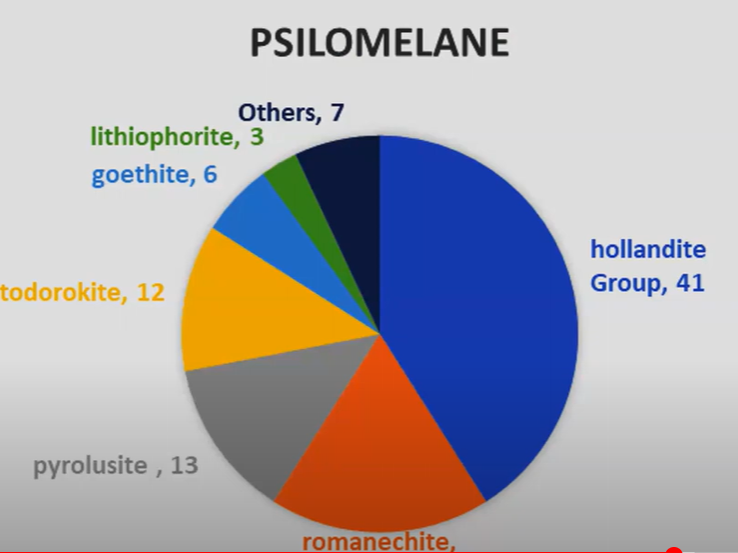

Jeff said he was grateful for his position with the Smithsonian which allowed him to conduct decades of research to probe the puzzles associated with manganese oxides. To find out why this mineral is increasingly receiving greater recognition and its links to environmental issues, go to the YouTube video and hear Jeff’s explanation and why mineral researchers often give its diverse crystal formations a group name “psilomelane.”

Manganese oxides are very complex and their combinations of crystal structures contain a lot of unresolved mysteries. The SI has hundreds of specimens needing analysis.

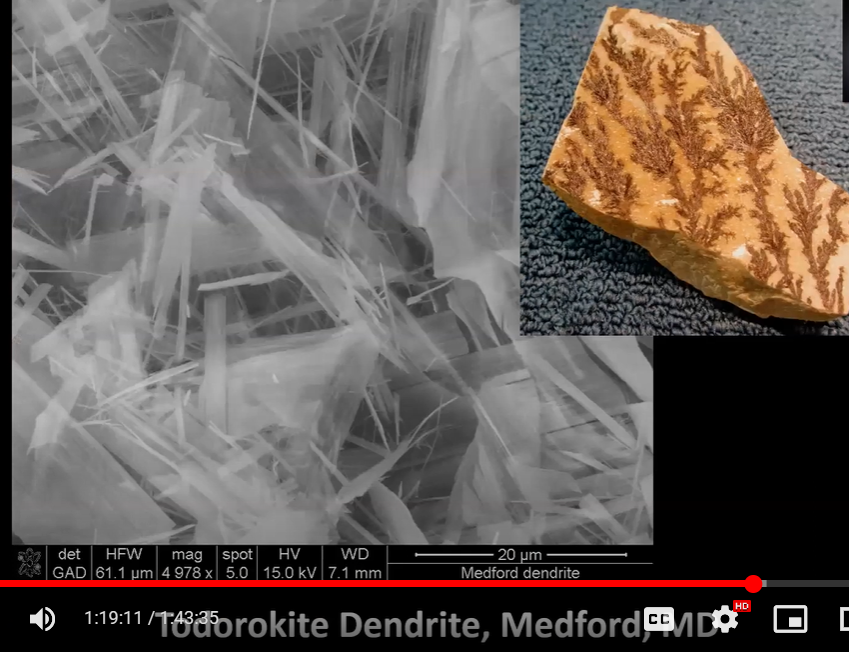

One of the more beautiful specimens of manganese oxide is a dendrite from Maryland, shown below:

Favorite Travels and Field Collecting Trips

During his decades with the Smithsonian, Jeff traveled to cool places such as Antarctica and the Arctic, and many warmer places in-between.

To learn where Jeff visited and had “the best mineral collecting day in my entire life,” visit the YouTube video of this presentation.

And, if you are curious about learning why this Goethite and its mysterious colors is one of Jeff’s favorite minerals, you know how to find out.

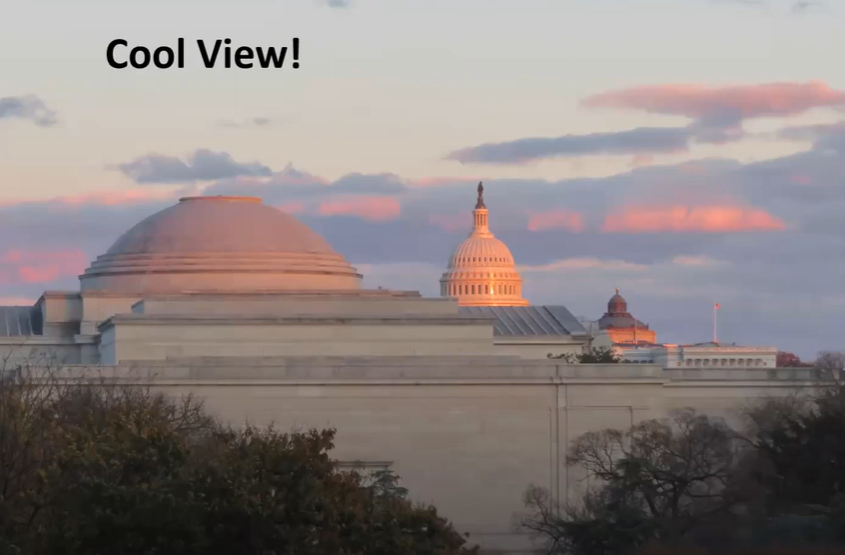

A Room with a View

In conclusion, imagine coming to your office each day and having the view in the photo below. This, Jeff said, was the last of his top ten musings and favorites he shared with his friends at the MSDC mineral club meeting.

Question and Answer Follow-up Session

A number of the people attending Jeff’s presentation were docents who have been volunteering and helping the public understand and appreciate the gem and mineral exhibits. View the video and listen to their short reports of how visitors to the Museum reacted to the exhibits that earlier Smithsonian geologists, and more recently Jeff and his colleagues, spent their careers building. Jeff concluded by thanking everyone for their support. He asked that upon his retirement, they continue to support his colleagues and the mission of the Smithsonian and Department of Mineral Sciences.

To view the video of Jeff’s presentation in its entirety, click on the following link: Musings of a Mineral Museum Curator - Dr. Jeffrey Post, Smithsonian - YouTube